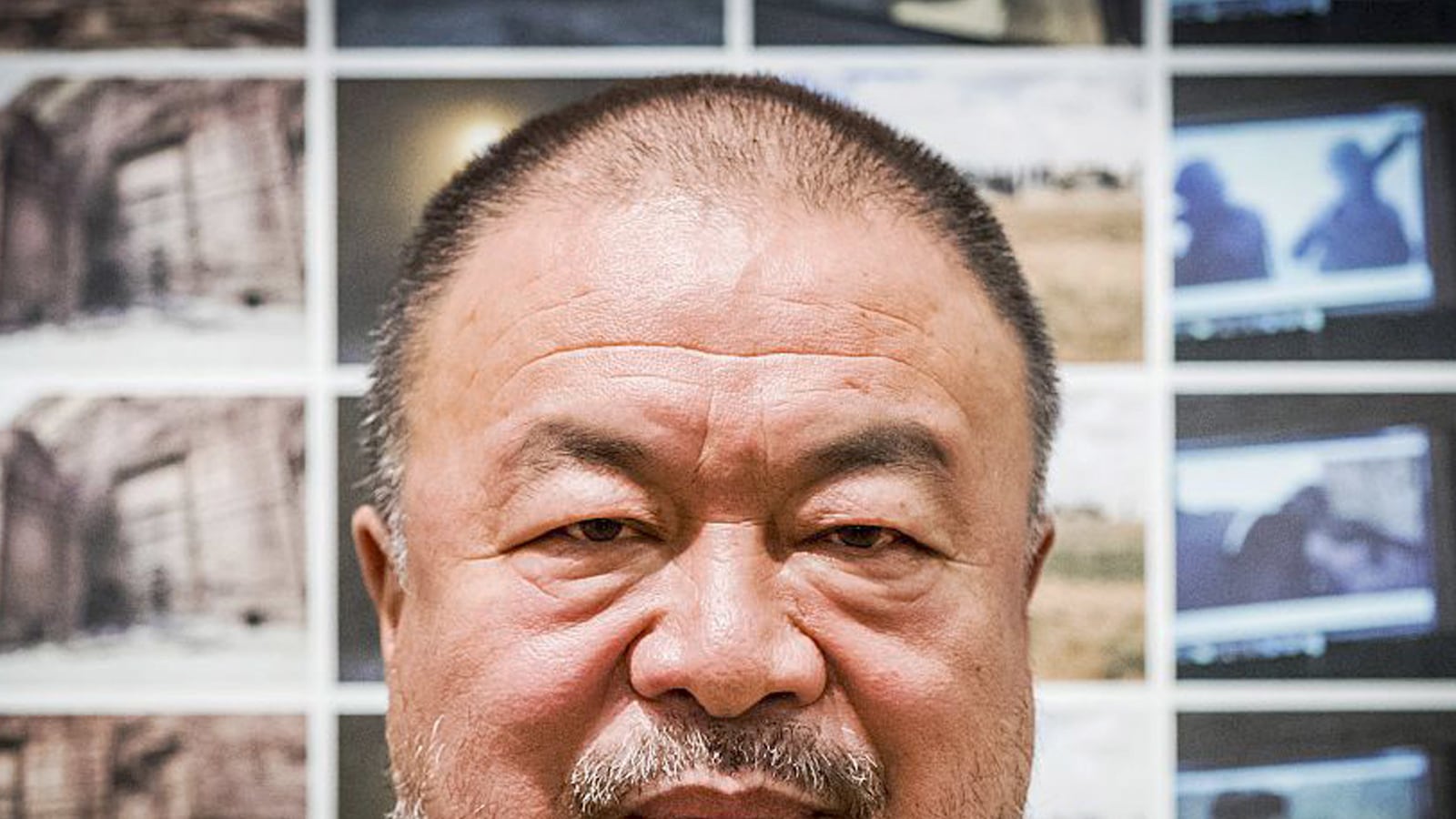

Ai Weiwei, introduced at the Brooklyn Museum Saturday afternoon as “the most recognized artist in the word,” was there to perform as an artist. Then things got real.

Ai sat down at the Museum, which put on a major retrospective on his work in 2014, to promote his four gallery shows in the city this month in a sit-down with Cuban-born dissident artist Tania Bruguera.

As she opened up by talking a bit about both of their art, activism and experiences with their respective native governments, he fiddled with his phone.

When it was his turn to talk, Ai told the crowd assembled at the museum and those watching on a livestream how much he appreciated being there to talk with them, and how much fun he’d had posing for selfies beforehand. If the talk didn’t go on too long, he said, there might be time for him to be in more selifes afterward.

Then he painted a broad picture about China’s modern art movement, speaking generally of its transition from subversive art to commercial art.

Ai said the label of a Chinese avant-garde dissident artist wasn’t one he had assigned himself but rather that been bestowed on him by Western media. Speaking about Chinese dissidents more generally, he declared: “When there is no freedom of speech, there is no freedom.”

From there, he discussed the 2008 earthquake in China in which tens of thousands died, including at least 5,000 children killed in shoddily constructed school buildings that became a major focus in his art at the time--solidifying his standing as activist artist.

It also drew the hostile attention of the Chinese government as it harassed and pressured parents who lost children into silence, with “seven officials per parent to suppress them under the idea of stability and harmonious society.”

Bruguera asked Ai where he now considers himself in the “political situation.” He said he has no clear party, since “I consider myself an individual,” which seemed an exceptionally American answer.

About his 1995 photographic and performance piece, Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn, in which he did just that, destroying the 2,000-year-old cultural artifact, one of many he had painted over, Ai said that while many people treated it as a serious statement it was “more or less of a joke.”

Brugera then asked his thoughts on the artist Maximo Caminero, who destroyed another of Ai’s own painted vases in the same manner while it was on display at an exhibition of the Chinese artist’s work at the Perez Art Museum in Miami. Ai said that Caminero had a “right to state his mind and do that gesture, but have to take responsibility for that gesture,” adding that “normally, you do that to your own property.”

Moving on to his photographic series, Study of Perspective, where he artistically flipped the bird to famous monuments throughout the world, including Tiananmen Square and the White House, Ai said it was about “freedom of speech,” and that there was “no excuse to not give out your voice.”

That voice, Ai implied, was uncompromised, since he “never negotiates with art or art world” and that “this is what I do—take it or don’t have me.” He added that “not everyone is as lucky.”

Bruguera asked about the tension between Ai's role as an activist artist and his immense financial success, and he called himself “a so-called political artist.” Still, he said, “you play the game,” and argued that if as an artist he had been politically active yet financially poor, that would show that his political activism wasn’t successful.

Bruguera kept pressing as Ai shifted in his chair and seemed to become a little frazzled, asking about his highly controversial photograph recreating the grimly iconic image of 3-year-old Syrian refugee Aylan Kurdi’s body washed up on a Turkish beach.

Ai, who took the shot while spending the beginning of this year helping refugees on the Greek island of Lesbos, said of its critics: “I don’t react to them. They react to me.”

He went on: “I’m an artist, not a priest. I’m not saying this is right or wrong, I’m raising questions,” to which the audience flooded him with applause. He responded to that by declaring “I don’t give a damn shit about it,” which was met him with more applause which he obliged with more swearing, saying “take it or fuck it.”

Bruguera, though, pressed the question, replying that “sometimes we have to fuck the artist too,” and Ai began almost shouting, pressing her to name the name the exact number of Syrian refugees who have died while trying to cross over to Europe. She did not, and he spat out that she was only a “partially political artist.”

Bruguera, showing grace and dignity as Ai escalated the exchange, then asked his thoughts on how to help improve conditions for the oppressed, and specifically what an artist can do to improve the Syrian refugee situation. He declared that “art can teach us to be a real person.”

Bruguera asked if such art could create a societal shift. Ai replied that “the problem will never be solved and always be there. We use our time to solve our own problems.”

The audience question and answer session that followed brought out an even more theatrical side of Ai. He dismissed some questions with Zen master-type non-sequitur replies and rerouted others as his hearing, the microphones, and his previously demonstrated fluency with the English language all seemed to selectively fail him. He spoke again about his dislike for being labelled a political artist, “because every artist and all art is political.”

When he was asked if has been in contact with his former lawyer in China or knows what is going to happen to him, Ai—who spent 81 days in jail there in 2011 on dubious charges of tax evasion—said “Liu?” He added that the lawyer had received 5 years of house arrest and that while they had Skyped a couple times, the lawyer was OK and at this point there is “not much anyone can do.”

Perhaps Ai’s questioner had meant to ask about Liu Xiaoyuan, but it’s curious that the artist—who in recent years has made statements to imply there is much less political oppression in China, which last year lifted the travel ban it had imposed on him--would have assumed that, rather than mentioning his former lawyer Xia Lin, who last month was sentenced in a Chinese court to 12 years imprisonment on dubious and widely condemned fraud charges.

(For context, Laura Daverio, a foreign correspondent who's been covering China for over 10 years, told the Daily Beast, "In the last 4 years, since the latest change of leadership, the space for dissidence has been narrowing and human rights lawyers have been specifically targeted.")

As the questions continued, Ai publicly asked the offstage staff if there was a time limit to this Q-and-A thing, saying with evident disbelief that “there was a very long line.” He then turned his attention back to his audience, warning them that there wouldn’t be any time for selfies if this went on.

The next several questions were peppered by announcements by some unseen entity that “these are the last 2 questions,” which made the whole thing feel even more like a performance art piece.

When a questioner then asked Ai about China’s new Social Credit system intended to give a number rating to the trustworthiness of each citizen, he made some motions that perhaps suggested he couldn’t hear or understand the question but remained silent until his questioner gave up.

Finally, the last question was announced, and a woman used it to tell Ai what an amazing artist she thought he was.

But just before the unseen announcer declared that that was the last question, a woman jumped the mic to demand Ai square his statement that artists have to take responsibility for their gestures with his reproduction of the drowned Syrian toddler and declaration that Bruguera was just a “partially political artist,” since she didn’t know how many Syrian refugees had drowned.

Ai again stayed silent, leaving Bruguera to reply. And with that, he was off the stage--and the hook.