On Monday night, a black gay man was attacked for existing in both of these identities.

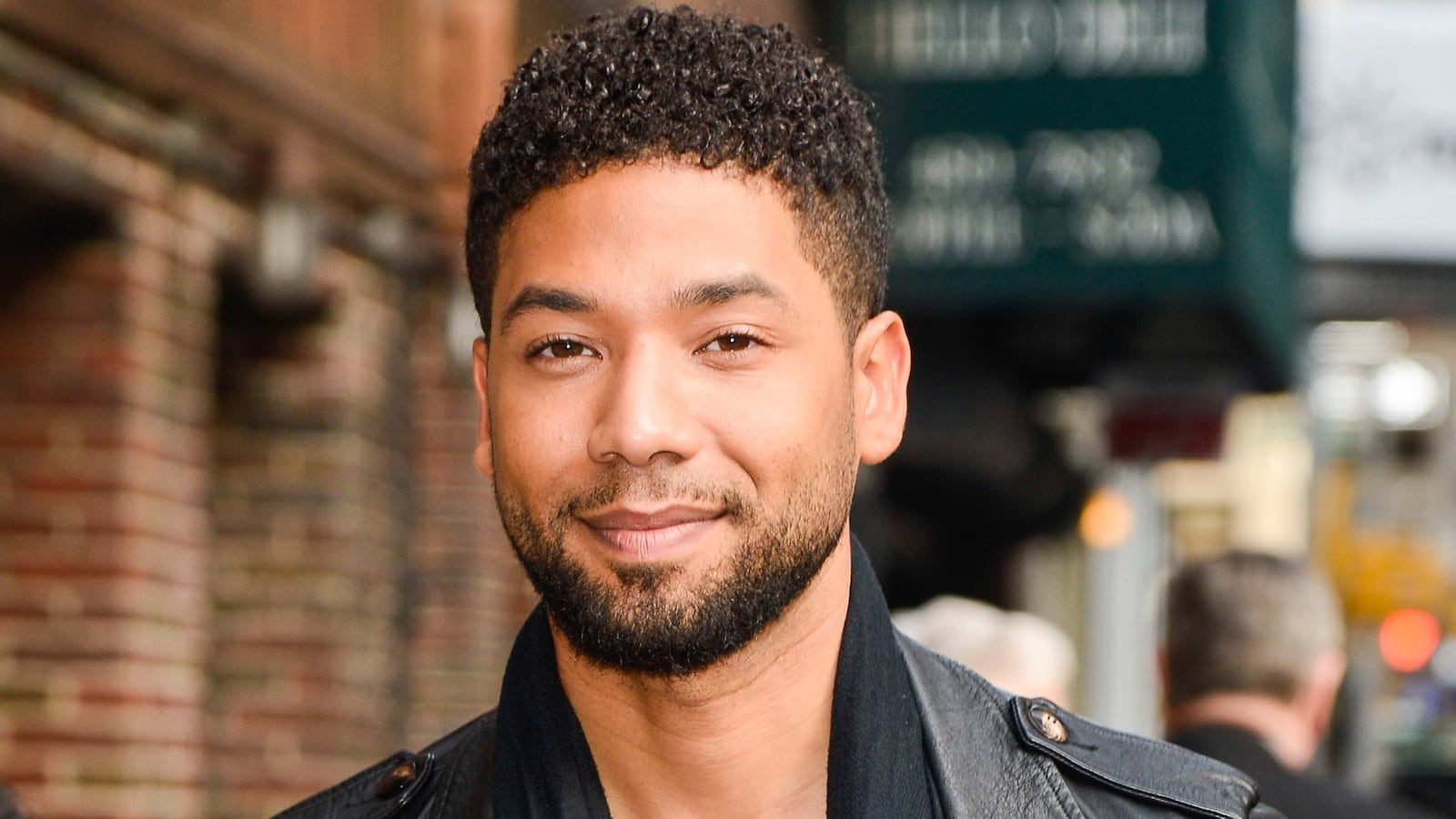

Empire actor Jussie Smollett was hospitalized after allegedly being assaulted in Chicago by two individuals who also tied a noose around his neck, and who poured an unknown chemical substance on him. The unidentified culprits appear to be Trump supporters who, according to TMZ, yelled at Smollett, “This is MAGA country,” along with hurling racist and homophobic slurs.

A Chicago Police spokesperson told The Daily Beast that the attackers' genders were unknown (TMZ reported it was two men), and that their faces and hands had been covered. The police spokesperson said it was unknown if, as TMZ reported, they had been wearing ski masks. “There is no report of that being said,” the spokesperson said of the allegedly shouted, “This is MAGA country.”

Later, it was revealed that in a supplemental interview Smollett had told cops that his attackers had shouted, “MAGA country.”

The Daily Beast has reached out to Smollett for comment via his representatives.

Regardless of the details surrounding whether or not these attackers are Donald Trump supporters are not, we do know that six days prior to Smollett’s assault the Empire actor—whose character is one of the most impressively-written black LGBT characters on television—received hate mail sent to Fox Studios in Chicago that threatened, “You will die black f**.”

It shouldn’t be a coincidence that such bigotry escalated from written hate mail to physical violence. History often showed us during the Jim Crow era of the 20th century that discriminatory laws led to lynchings and other legalized acts of white supremacy. What happened to Smollett was a form of white terrorism that targeted both his racial identity and sexual orientation simultaneously.

People on social media have also been trying to encourage others to stop trying to defining this matter as solely being racist and/or homophobic, but to consider the intersections of both:

But despite these recent calls for intersectionality, America strives to enforce these binaries that are proving to be more toxic than helpful.

As of the publishing of this op-ed, television celebrity Ellen DeGeneres has still remained silent on Smollett’s attack.

It should be noted that the Empire star made his first-ever public coming out announcement while on her hit show in 2015.

DeGeneres, a white lesbian, has come under fire this month for defending comedian Kevin Hart for making homophobic jokes that cost him his Oscar hosting gig. “You have grown, you have apologized, you are apologizing again right now,” DeGeneres told Hart on her segment. “You've done it. Don't let those people win. Host the Oscars.”

But the problem with DeGeneres weighing in was that she ignored who was directly affected by Hart’s homophobic rhetoric: black gay men. In a 2011 tweet, Hart suggested he would tell his son, “stop that’s gay,” if he caught him playing with a dollhouse and would respond by breaking the toy over the child’s head. The target of Hart’s punchline was black gay youth—not a white older lesbian—which made it all the more painful for her to extend him grace.

We have seen similar instances of intersectional matters being whitewashed, such as when prominent news outlets ignored the fact that a sweeping majority of the Orlando Pulse nightclub victims were Latinx queer people. Or when it wasn’t emphasized by some that the victims found dead in Democratic donor Ed Buck’s residence were black gay men.

These forms of visible erasure do more to ignore how intense the oppression is if you are both of color and LGBTQ.

As a black gay man, I often face marginalization in ways that are both unexpected and cruel. I’ve experienced racial discrimination within my own local LGBTQ community in Philadelphia in gay bars and nightclubs. But I’ve also dealt with the homophobia with my own black community, and such instances deeply impacted how I chose to live my truth for quite some time.

To try to put me in a binary as being either black or gay is a disgusting way of viewing diversity and understanding the lived experiences of those who live within the fringes of society.

It’s important to acknowledge that the hate Smollett faced as a black gay man was a bi-product of society’s tolerance of racism and homophobia. There is racial bias in how LGBTQ people are protected in mainstream society, as there is homophobia in how black people are protected within their own community.

Why isn’t there more support for murdered black trans women within the Black community as for slain cisgender black men? Why aren’t there more efforts to eradicate the HIV/AIDS crisis still impacting black gay men as there were for white gay men decades ago? These are the questions I ask myself daily when people try to suggest that I choose between an LGBTQ community or a black one.

If we are to truly be a society that is serious about combating white supremacy, we have to recognize that racism and homophobia are byproducts that prolong such hate.

A black homophobe who chooses to isolate black LGBTQ people within the community is furthering the same tactics used by white supremacists to persecute us all. White LGBTQ people who continue to ignore the struggles of LGBTQ people of color are practicing the same level of racism that does more to divide than unite. It’s high time we call these forms of anti-blackness out within our own spaces as we try to combat more high-profile instances.

Moving forward, do not treat what happened to Smollett as an isolated incident but something that’s a glaring consequence of society’s entrenched struggle with race and sexuality. If bigots can’t seem to separate their victims’ dual identities, neither should we. Spend less time forcing black gay men like me to choose one, and strive to protect and defend both.

Ernest Owens is the Writer at Large for Philadelphia magazine and CEO of Ernest Media Empire, LLC. The award-winning journalist has written for USA Today, NBC News, BET, MTV News and several other major publications. Follow him on Facebook, Twitter, or Instagram and at ernestowens.com