Location, location, location. It may be a trite saying of over-gelled real estate agents, but it’s one that, at its core, is also true. In many ways, our lives are defined by place—the places we’re from, the places we choose to live, the places we are forced to leave.

But what if our cities and countries weren’t permanent metropolises around which we crafted our lives but instead dynamic organisms that were constantly being moved and reshaped?

That’s what one radical architect, Ron Herron, asked himself in the 1960s. His answer: the “Walking City.”

In 1961, six British architects including Herron formed a new collective in reaction to what they saw as the boring monotony of post-war modernism.

The countercultural ingredients that would come to define the 1960s were brewing beneath the surface, and across the Atlantic, the pop art movement was just starting to emerge. Archigram’s idea was to take these creative elements that were influencing fashion, art, and music and apply them to architecture.

“Archigram wanted to celebrate the upbeat side of postwar life: the Britain of fun fairs, fashion, creative ferment in the performing arts, assertive sexuality and the divine absurdity of living in an imperial city that no longer ruled over an empire,” Herbert Muschamp wrote in a 1998 article for The New York Times.

While its members were architects, their creative output centered around a magazine in which they published their futuristic, highly inventive ideas. These ideas were a little out there, but in the decades since Archigram disbanded in 1974 their work continues to influence leading architects and designers.

Part of the reason Archigram could be so radical is that they trafficked mostly in ideas. Without the constraints of needing to build their designs, the Archigram members could rethink how buildings and cities function in a vacuum separate from the practical considerations of how these revolutionary concepts could be brought to life.

Some of their most famous ideas are their earliest ones. In 1962, Peter Cook envisioned an “Instant City” inspired by the idea of traveling circuses in which all-inclusive entertainment venues could be dropped (by air balloon, of course) or trucked into rural towns.

He also created plans for a “Plug-in City,” in which permanent tower-like structures housed rooms that could be constantly moved and swapped—or “plugged in”—between different towers around the city.

But Herron wanted to push these ideas even further. Rather than creating flexibility in just the contents of the city, why not endow the city itself with the power of mobility?

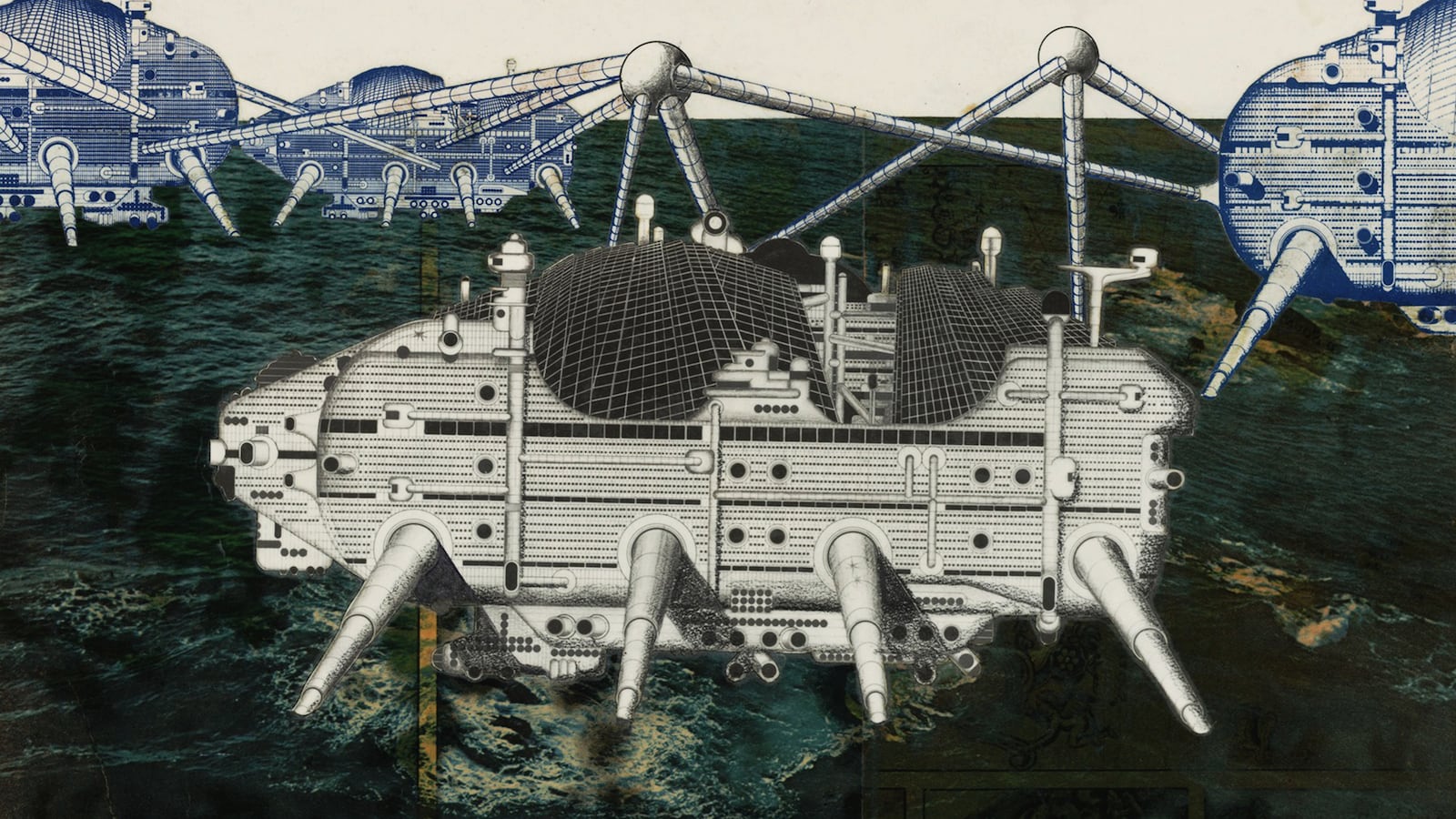

In 1964, he introduced the idea of a Walking City. His drawings for this creation are right out of a comic book or a sci-fi movie. He envisioned cities made of giant oval, multi-story containers (his drawings suggest they could contain as many as 30 floors), perched high on steel, stilt-like legs.

Often likened to insects, these mobile pods would be able to roam the globe, containing all of the services they needed to survive, as well as the ability to plug in to the resources of whatever location they happened to be in. They could strike out on their own or combine and recombine with other pod cities in an endless game of musical chairs of place and community.

In his book Phantom Architecture, Philip Wilkinson says Herron may have been influenced in his designs by the Maunsell forts that floated in the Thames during WWII. In the mid-1960s, they were back in the news as one was commandeered and turned into a pirate-radio station.

Because of the Walking City’s likeness to these instruments of war, Wilkinson says Herron received some criticism that his creation was a fascist war machine. But that wasn’t the case at all.

Instead, Wilkinson says the “metallic forms of the city were more like survival pods than weapons.” Herron was, after all, working in the midst of the nuclear concerns of the Cold War.

Their defining feature, however, was their adaptability. Archigram’s leading characteristic was an embrace of technology and the creative powers it endowed (which is one of the reasons their work often takes on a sci-fi sheen).

Herron’s vision for the Walking City is that it could be anything that was needed. It could walk itself to a rural area if safety and distance were called for; it could combine with other walking pods and form larger communities; or, it could even join up with a major metropolis.

In one of Herron’s most famous drawings of the Walking City (Archigram pioneered the use of collage in their architectural renderings and the result is drawings that are works of art in and of themselves), insect-like metal pods wade through the Hudson River heading for the bright lights of New York City.

In an advertisement for the latest sci-fi flick, this would be an image of an alien invasion. But in Herron’s rendering, it is a sign of the adaptability of a utopian world where place would be something that was constantly mutable and versatile, even able to join up with a behemoth like Manhattan.

“Concepts such as prefabrication, lightweight structures and adaptability were not invented by Archigram,” Wilkinson writes. “But their questioning, their provocative graphics, and their flair for publicity brought such ideas into the public eye, and made it possible to entertain, seriously for a while, the notion that a city could walk through water and plug itself into the infrastructure of Manhattan.”

As technological as these concepts were, they were also wholly fantastical. Herron didn’t concern himself with the practicalities of building them, such as how such a large “city” could stand on such telescopic steel legs. And it’s anxiety-inducing to even think about how a community living in one of these pods would ever agree on where to move to next.

But it does present ideas that continue to influence how we think about where we live, the structures we live in, and the often contentious borders that we have created to keep people in place.

Archigram may have only existed for 13 years, but the ideas they put into the world during that time continue to shape our culture. They helped to publicize concepts like prefabrication that continue to influence current inventions like modular and micro housing that are being created to tackle our society’s ongoing problems.

Their dedication to no-limits dreaming of fantastical creations that could reshape our world has inspired many architects and designers to create wonderful—and sometimes crazy—visions of their own perfected cities.

“This was never as much as we had wanted it to be. Archigram gave us a chance to let rip and show what we wanted to do if only anyone would let us,” Herron said in an interview shortly before his death.

In 2002, eight years after Herron died at the age of 64, Archigram’s work was honored with the top prize in architecture, a Riba gold medal.

“Even today the work of Archigram reflects a freshness, a courage and a creativity that is simply mind-blowing,” Riba’s then-president, Paul Hyett said. “These guys started in the days of the Mini car, miniskirt and the dawn of a mini-technology; they were tremendously exciting times. Their love and passion for architecture and their insatiable desire to posit alternative futures for our society, such as Ron Herron’s tantalizing images of Walking City, still dazzle and delight today.”