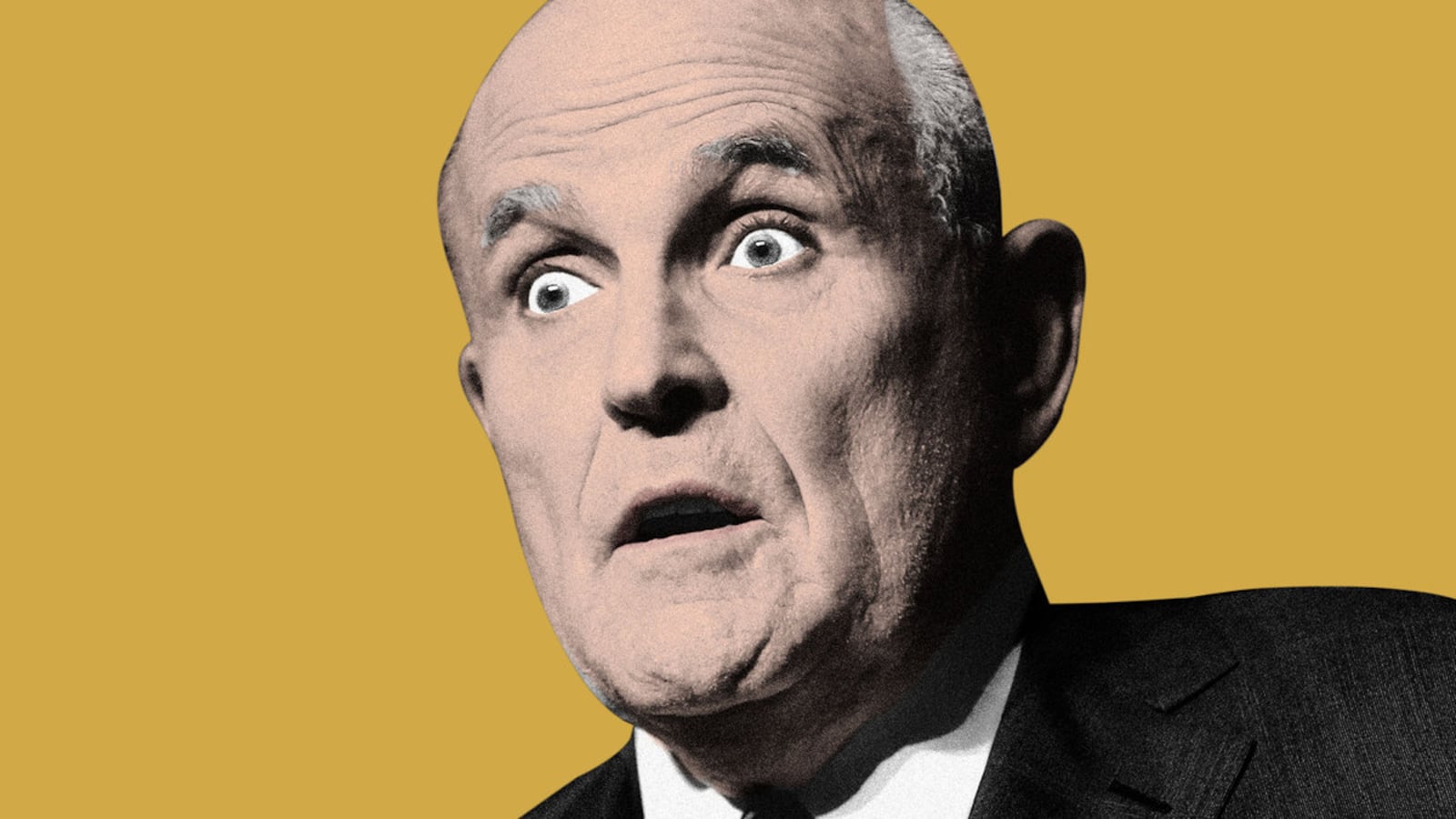

House Republicans have a big, Rudy Giuliani-shaped problem.

President Trump’s personal attorney has spent the past few months repeating his various Ukraine conspiracy theories to anyone who’ll listen, and witnesses say he was pressing Ukrainian officials for a quid pro quo. If you’re in the business of defending the president from impeachment, that’s a problem, and the only way to deal with it is to try to put some distance between Trump and his own lawyer. It’s not an easy task, so how are Republicans going about it?

Welcome to Rabbit Hole.

The trouble with Rudy: Trump administration officials have tried to make a key distinction between the desire for a corruption investigation of the Ukrainian energy company Burisma and a political attempt to dig up dirt on former Vice President Joe Biden, whose son Hunter was one of Burisma’s most prominent board members for a time.

But over the past few months, Giuliani has been explicit about what otherwise would have been discreetly implicit. In May, The New York Times reported that Giuliani was headed to Ukraine to press the newly elected government to start an investigation of Hunter Biden and his work for Burisma. On Fox News after the Times story broke, Giuliani repeated the conspiracy theory that Joe Biden had stopped an investigation into his son’s company. “That stinks. The facts are stubborn and eventually this is going to have to be investigated,” he said.

U.S. Ambassador to the European Union Gordon Sondland also testified that over the summer, “Giuliani conveyed to Secretary Perry, Ambassador Volker, and others that President Trump wanted a public statement from President Zelensky committing to investigations of Burisma and the 2016 election.” Giuliani’s demands on the Ukrainians, including a statement from Zelensky about the investigations, “were a quid pro quo for arranging a White House visit for President Zelensky,” Sondland said.

More darkly, Lev Parnas, a Ukrainian-American businessman and former client of Giuliani, has since claimed that Giuliani instructed him to tell Serhiy Shefir, an associate of President Volodymyr Zelensky, that the Ukrainian government needed to begin an investigation of the Bidens in order to secure Vice President Mike Pence’s attendance at Zelensky’s inauguration, according to The New York Times. Giuliani and Shefir have since denied the allegations, as has Parnas’ business partner, Igor Fruman. Parnas made the allegations after he and Fruman were arrested on federal campaign finance charges in October.

Rudy = Trump? The problem for the president’s defenders is that they don’t want Trump to appear anywhere near that kind of explicit demand for an investigation of his possible 2020 campaign rival. Unfortunately for them, Trump repeatedly pointed to Giuliani—who was loudly seeking precisely that—as the point man representing his interests on the subject of Ukraine.

Trump twice directed officials to work with Giuliani on Ukraine. Trump established what became known as the “three amigos” of Ukraine policy during a May 23 meeting when he told Energy Secretary Rick Perry, Sondland, and Ukraine envoy Kurt Volker to work with Giuliani on Ukraine. During the July 25 phone call between Trump and Zelensky, the president said, “I would like [Giuliani] to call you” and that “Rudy very much knows what’s happening and he is a very capable guy. If you could speak to him that would be great.”

Going for distance: Until recently, there wasn’t much need for Republicans on the House impeachment inquiry to try to distance Giuliani’s Ukraine adventures from the president because Volker, unprompted, had done it for them. When asked if he believed Giuliani was speaking for Trump in his various interactions with Ukrainian officials, Volker testified that he didn’t: “I believe that he was doing his own communication about what he believed and was interested in.”

Sondland, however, took a very different view of Giuliani’s role as a Trump emissary. Under questioning from Democrats, he said it was his understanding that Giuliani was representing the president’s requests and that the May 23 “three amigos” meeting with Trump amounted to an instruction to work with Giuliani on Ukraine.

That testimony hasn’t sat well with House Republicans. Their counsel, Steve Castor, tried to suggest that the words “talk to Rudy” from Trump weren’t an instruction but an abstract sense of exasperation. “He said, ‘Talk to Rudy.’ You subsequently said it was sort of like ‘I don’t want to talk about this,’” Castor said on Wednesday. “So it wasn’t an order or direction to go talk with Mr. Giuliani, correct?”

Sondland reiterated that he believed he’d been instructed to work with Giuliani. When Fiona Hill, the former Trump National Security Council senior director for Russia, reiterated that impression during her testimony on Thursday, Castor again pounced to suggest otherwise.

“I mean, there’s some ambiguity in the direction to work with Rudy Giuliani—Ambassador Volker said the president dismissed Ukraine and said, ‘Oh, if you want to work on it just go talk to Rudy.’ And Ambassador Sondland took that a little bit differently,” he said.

Parnas and Fruman: If Republicans want to insist Giuliani wasn’t representing the president’s interests in Ukraine, whose interests was he pursuing and why was he so interested in Ukraine? House Republicans haven’t offered a concrete answer, but they have left a few hints.

After Sondland stated his conviction that he was carrying out Trump’s orders through Giuliani, Castor reminded him that Volker had testified Giuliani “was doing his own communication about what he believed and was interested in.” Castor then pointedly reminded Sondland that “Mr. Giuliani had business interests in Ukraine, correct?” and added “With Messrs. Parnas and Fruman, correct?”

The implication left in the air is that there’s a possibility Giuliani may have been influenced by the agenda of his Ukrainian-American clients, Parnas and Fruman, rather than by the president—a move that would distance Trump from some of Giuliani’s actions.

Federal prosecutors in New York have charged Parnas and Fruman with campaign finance violations and alleged that the two men acted effectively as straw donors to a Republican political action committee on behalf of an unnamed Ukrainian oligarch.

The two men were also reportedly interested in getting into the liquefied natural gas business in Ukraine and allegedly sought a change of leadership at Ukraine’s state-owned natural gas company, Naftogaz.

Not sitting well: The possibility that Republicans could be trying to paint Giuliani as a rogue operator pursuing his own agenda rather than Trump’s hasn’t escaped the mayor. After Castor’s exchange with Sondland on Wednesday, Giuliani tweeted that Castor “doesn’t do his own research and preparation” and that Giuliani has “NO financial interests in Ukraine, NONE!” and “would appreciate his apology.”