FTX founder Sam Bankman-Fried has spent weeks listening to his former executives, his employees, and even his ex-girlfriend testify about a massive fraud he allegedly orchestrated at the crypto exchange.

On Thursday, he finally got to tell his side of the story. But in a bizarre twist, the jury wasn’t present to hear any of it.

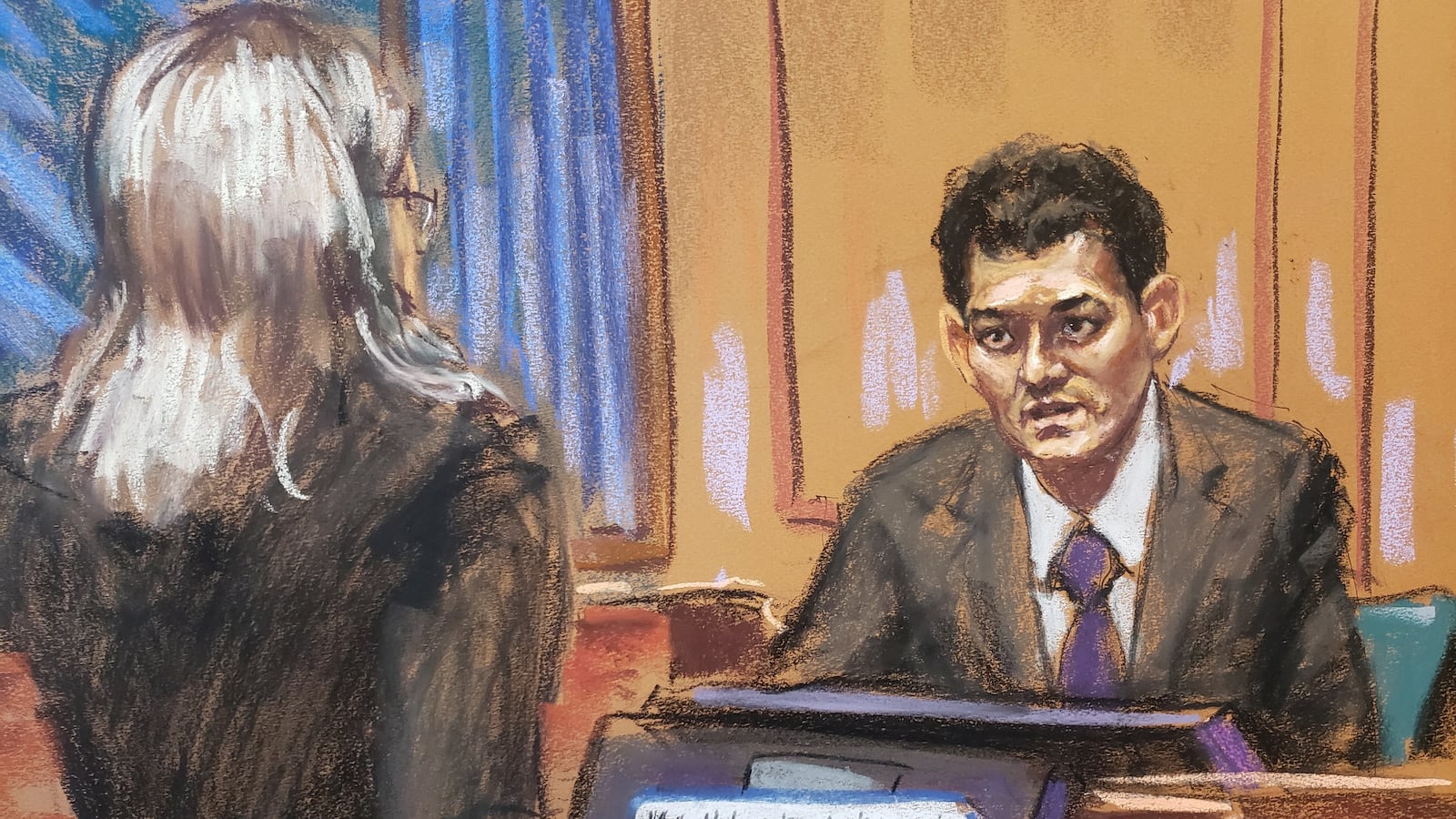

Judge Lewis Kaplan said he couldn’t rule on whether elements of the testimony would be admissible without first hearing it himself, effectively turning Thursday’s proceedings into a practice run. It was an unusual decision. Kaplan, who has served on the bench for nearly three decades, said he hadn’t had a hearing “of this nature in quite a long time,” or perhaps ever. The unexpected rehearsal may have served Bankman-Fried well, giving him the chance to refine his performance with reduced stakes. Federal prosecutor Danielle Sassoon was far more pointed in her questioning on Thursday than she had been with previous witnesses, and at times Bankman-Fried appeared nervous and evasive. He swiveled in his chair, frequently stammered, took swigs of water, and gave circuitous answers that left Sassoon frustrated.

Kaplan also rebuked Bankman-Fried for failing to be direct in his responses.

The proceedings largely centered on technical elements of Bankman-Fried’s work at FTX and his crypto trading firm, Alameda Research, including document retention, terms of service, and his consultation with attorneys in the run-up to the firm’s collapse in 2022.

He repeatedly testified that he did “not recall” pieces of information, such as details about a document-retention policy that he claimed allowed him to auto-delete messages with other executives on the encrypted app Signal—though he said he no longer has a copy of the policy.

Sassoon referred to the missing memo as the “supposed document” and asked Bankman-Fried to explain when it would be appropriate to delete corporate records.

“It’s hard for me to answer in the abstract,” he said, sporting a tamer haircut than his old signature mane. Broadly, he asserted, the policy allowed for the deletion of “informal business conversations,” such as rough drafts of spreadsheets and preliminary conversations about company strategy.

Sassoon brought up testimony from earlier in the trial alleging that Caroline Ellison, the former head of Alameda (and Bankman-Friend's ex-girlfriend), sent him multiple versions of company balance sheets on Signal, and a separate instance in which he and other executives discussed a multibillion-dollar hole in FTX’s customer deposits. That conversation gets to the core of prosecutors’ case: that Bankman-Fried improperly took those deposits and used them to pay off debts and fund investments.

Ellison and former FTX execs Nishad Singh and Gary Wang—all of whom have pleaded guilty—accused their old boss of spearheading the operation. The activity was “heinously criminal,” Singh testified earlier this month, while Ellison said that Bankman-Fried “directed” her to commit crimes.

On Thursday, Bankman-Fried defended his proclivity for deleting materials, saying the habit traced to his days working at Jane Street Capital, a trading firm in New York, where he learned the so-called “New York Times test.”

“Anything that you write down might end up on the front page of The New York Times,” he said, potentially causing embarrassment, even if leaked materials had been taken out of context.

Bankman-Fried will likely testify before the jury tomorrow, which several legal experts told The Daily Beast poses a huge risk; two experts likened the decision to a “hail Mary” often used when a defendant’s lawyers believe they are losing.

“It gives prosecutors the opportunity to essentially retry their entire case,” said Robert Mintz, a white-collar defense attorney in New Jersey. “Experience [shows] that it’s very difficult for defendants to pull off.”

Given Bankman-Fried’s pretrial engagement with the press, “no one should be surprised that he is choosing to take the stand,” added Brian Klein, a former federal prosecutor. “But this is just rearranging the deck chairs on the Titanic.”