If you were a rioter at the United States Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021, you may have felt the whole world was with you—or the part of the world that supported what you did.

President Trump himself had urged you to march to the Capitol Building. A crowd walked alongside you down Pennsylvania Avenue. People chanted with you about attacking Mike Pence, crashed through the police lines with you, helped you to break windows and march through the building.

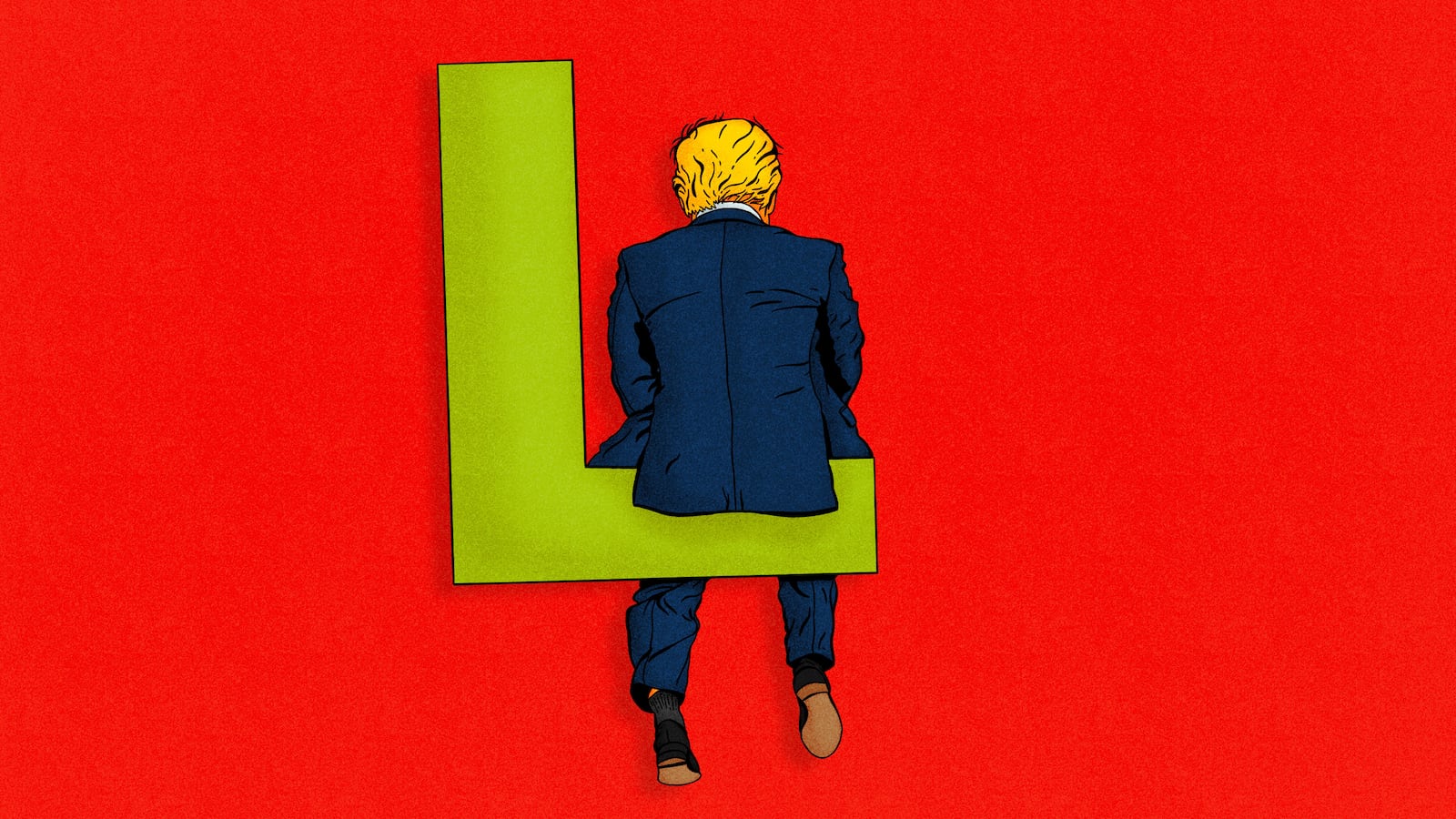

After your arrest, it turned out that you had always been alone. Your mob vanished. You had only your lawyer as companionship at trial. You had no friends as you sat at your sentencing hearing. You alone were imprisoned. You had not won. You were a loser.

Now Donald Trump himself knows that feeling—momentarily, because he may yet be acquitted in his hush money trial and go on to be re-elected president in November. As he sits, glowering in court in Manhattan, he himself may be reflecting that in 2020, he ruled the land. Republicans cheered him when he spoke. Marines saluted as he walked past. Air Force One jetted him around the world. People jumped both when he entered a room and to answer his phone calls. Masses of people packed his rallies. The Secret Service had to protect him from adoring crowds. He was what he aspired to be: a strong, and worshipped, man.

However, after his arrest, it turned out that Trump had always been alone. As the relatively empty streets outside court show, his mob has vanished. He has only his lawyer at his trial in Manhattan.

He has endured jury selection, listening endlessly to social media posts in which his fellow New Yorkers savaged him. He has sat through arguments about what subjects will be covered in cross-examination if he dares take the witness stand—the civil fraud judgment that cost him $400 million; violations of gag orders; the two verdicts in defamation cases that cost him $80 million; the settlement in which he dissolved the eponymous Donald J. Trump Foundation. If he took the witness stand, even conservative news outlets might find that cross-examination to be titillating.

Trump has listened to prosecutors deliver opening statements, meticulously summarizing the evidence of how he cooked the books of his company. He knows that the press will report these words accurately.

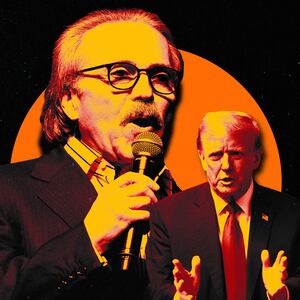

Trump has watched David Pecker, a friend for decades who published the National Enquirer, testify under oath about how he hid information from the American public to help Trump attain his highest achievement—the presidency of the United States. Trump has taken to Truth Social to vent his rage; he speaks to the press only about personal grievances; he fears that he will become what his father most scorned: a loser.

Indeed, for this moment at least, Trump knows deep in his heart that he is precisely that: a loser. Suppose that he is ultimately acquitted at trial. Suppose he wins the election. Suppose he is again sworn in next January. Does that erase the memory of these long six weeks of trial, when he knows, in his gut, that he has lost?

Friends or family of the accused attend some criminal trials to lend moral support to the suspect, and humanize the defendant to the jury. Not so—not yet at least—for Donald Trump. His family is nowhere to be seen. His wife, at least presently, is not to be seen at his side; his children have vanished; his loved ones have melted away.

After his arrest, he can no longer summon his mob. He asks the world to protest, but not a dozen supporters wave flags outside the courthouse. With only a lawyer for solace, he sits at the defense table, listening to the prosecutors explain his alleged offenses and hearing old friends and employees testify to his misconduct.

Trump was powerful, always among friends, and rich beyond measure. Now, in the words of Mother Teresa, he has learned that “the most terrible poverty is loneliness.”

Or perhaps Jean-Paul Sartre put it better: “If you’re lonely when you’re alone, you’re in bad company.”