It's hip to hate U2.

With number one albums across four decades, their very success undercuts the rebellious edge that’s at the heart of rock n roll. To their critics, they are four preachy late middle-age multi-millionaires from Ireland, serving up soul searching tunes with a social conscience. They don’t fight the power so much as they try to inspire the powerful, unapologetically leveraging pop-culture in the political arena, dining with presidents and prime ministers. When their last album, Songs of Innocence, was deposited into everyone’s iPhone for free, some folks took the generous if presumptuous stunt as a greater violation of privacy than the rise of China’s surveillance state.

But drill down on all the hipster conventional wisdom and the core complaint is earnestness. U2 are rarely dark or ironic. They aim for inspiration and sing about religion more than sex. They don’t play to identity politics or celebrate the superficial. They seem out of step in an age of Trump and Kardashian.

Good. We could use a bit of earnest uplift right now. Yes, sociopaths can succeed for a time and unapologetic narcissism can land you at the top of the charts or in the White House. But while cynicism is a fashionable defense mechanism it’s really just an excuse for inaction. As Timothy Snyder writes in his book On Tyranny, “Generic cynicism makes us feel hip and alternative even as we slip along with our fellow citizens into a morass of indifference.”

That’s why U2’s self-declared four-decade-long “war on apathy” not only remains worthwhile but feels more urgent than before. Over their career they’ve brought awareness to issues that might have escaped teenagers’ attention, from their legendary post-siege concert at Sarajevo to the successful effort at lobbying Bush-era Republicans to fund antiretroviral drugs in Africa (now under threat from the Trump administration) to the campaign to forgive the debt from developing nations.

If they occasionally overreach, that’s the cost of caring as opposed to simply staying cool and aloof. There are far worse sins than embracing the intersection of commerce and art, Caesar and Jesus. Today, even attempting to hold yourself to a higher standard invites attack for hypocrisy, as when the band was pilloried for tax avoidance. The safer celebrity pose is to affect indifference and then be celebrated when you do something surprisingly decent.

So it’s fitting that U2’s recently released 14th studio album, Songs of Experience, is a rumination on the importance of being earnest. It’s a dialogue with an earlier version of yourself about what really matters when you look back on your life – the real power of love after all the self-doubt and self-sabotage when finally confronted with the specter of death. That may sound trite, but think about the last time you heard pop-music celebrate the hard work of long-lasting love rather than lust, possession or obsession.

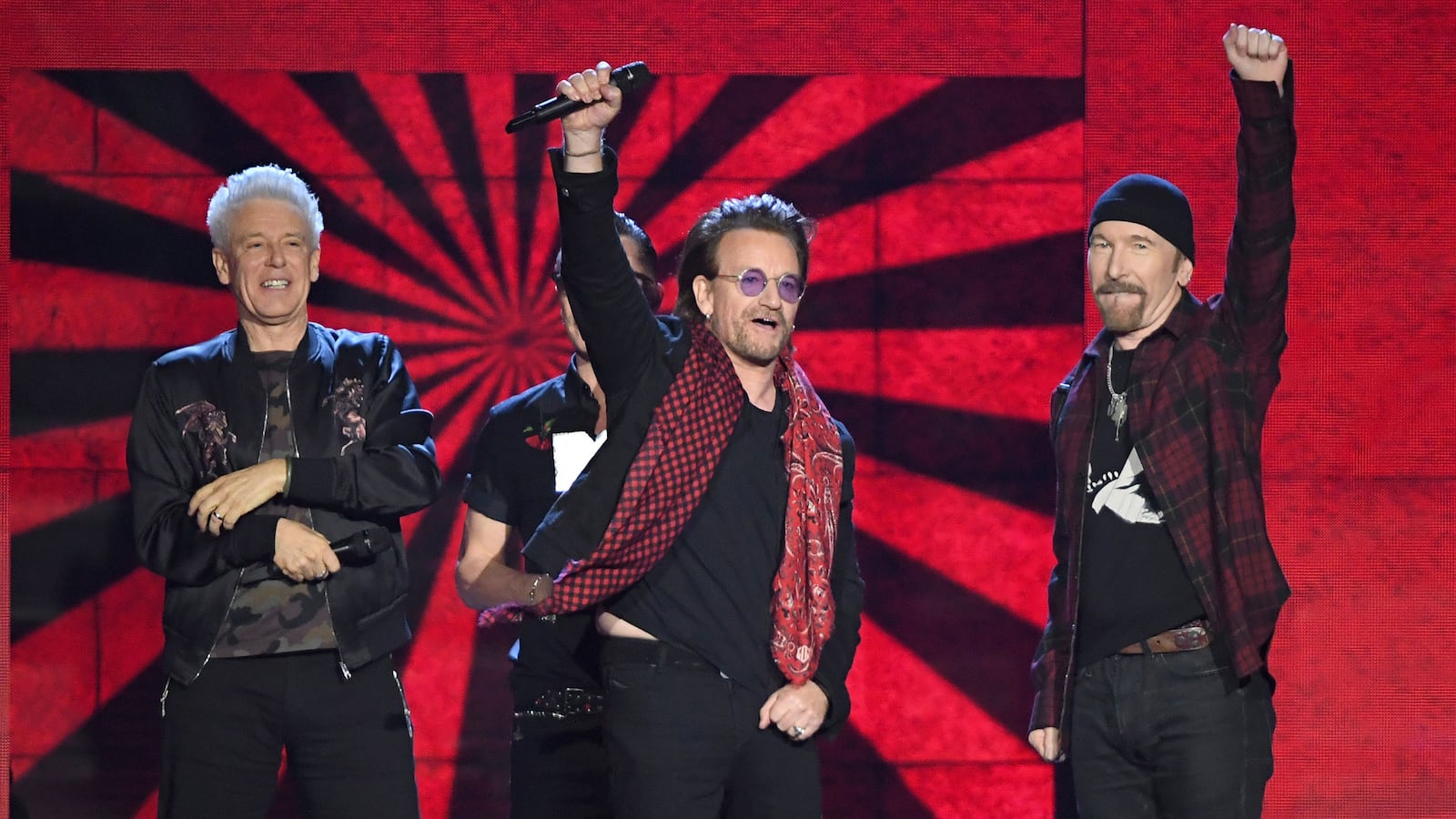

The deeper theme of the album is family, expressed by the cover image of Bono’s son standing alongside The Edge’s daughter. Yes, familial love is decidedly un-rock n’ roll beyond bitter odes to dysfunction, but realizing that your heart is walking around outside your body is a durable form of transcendence that doesn’t require drugs. The ballad “Landlady” is a tender ode to Bono’s wife Ali that captures the just-because-it’s-a-cliché-doesn’t-mean-it’s-not-true feeling of finally finding what you’re looking for at home. The same realization is celebrated on its opposite sonic number, “Love is Bigger Than Anything In Its Way,” a buoyant defiance of darkness that provided comfort on the recent December day when we buried my grandmother. Wisdom doesn’t always seem to have a pop-culture constituency but great art makes people feel less alone.

Songs of Experience fuses catchy if kitchy self-help choruses (“free yourself/to be yourself”), (“get out of your own way”), with Beatles-esque arrangements replete with string sections. If the lyrics seems a little on the nose, the band has never been one to find safety from self-consciousness in the intentional obscurity of word-play. They try to say what they mean and that’s a virtue in an age of deflection and deception.

But scratch the surface sincerity and you’ll find flashes of endearing weirdness. The album begins with the anti-anthem “Love Is All We Have Left,” which Bono imagined as a torch song sung by a robotic Frank Sinatra in a Blade Runner-style tragedy of knowledge beyond the ability to feel. “The Showman” takes the piss out of Bono’s front-man syndrome with the line “I’ve got just enough low self-esteem to get me where I want to go.” “American Soul” kicks off with a Kendrick Lamar sermon, while “Blackout” is a bouncing, adrenalin-fueled ode to living through the Trumpocalypse together (“Democracy is flat on its back, Jack/We had at all, and what we had is not coming back, Zak”). It’s a reminder that the stereotype of U2 as humorless prigs falls apart upon examination of the facts – (for a quick refresher, watch their Village People-tribute in the video for Discotheque).

U2 have always been uniters, not dividers, as their name promised from the beginning. They are about recognizing the “I” in “Thou” without dumbing it down and if you dig fixating on difference, they’re not going to be your jam. But life has a way of resetting back to the basics after you’ve burnt all your bridges in search of a pyrotechnic life focused on style rather than substance.

Especially at a time when the world seems to be going insane, finding solace in love for your family is a rational act of resistance with the added comfort of really mattering. “I know the world is dumb/but you don’t have to be,” Bono croons on the closing track, 13 (There is a Light). “Are you tough enough to be kind/do you know that your heart has its own mind/darkness gathers around the lights.”

Darkness does gather around the light. Haters always try to kill the apostles of hope. But that’s all the more reason to defiantly steer toward the light in the new year, asking “are you tough enough to be kind?”.