TORIBÍO, Colombia—When they kill one of your friends, something within you dies, too.

Jesús Mestizo, known to those close to him as Chucho, was murdered earlier this month by cartel gunmen in the so-called “Golden Triangle” of southwest Colombia, one more victim in a series of massacres and targeted assassinations that have claimed scores of lives in the Triangle this year.

Only this time the victim was my friend.

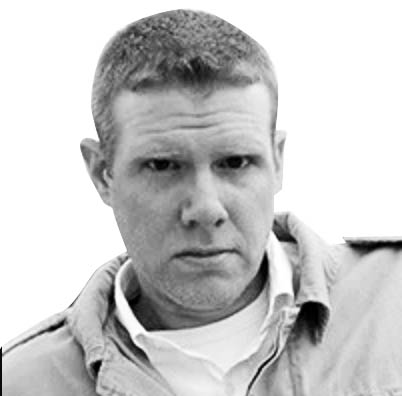

I first met him in late 2015. As the leader of a human rights group, Chucho was able to arrange for me to meet with farmers growing illicit coca and marijuana plants. Because such sites often are hidden away in remote corners of the sierra, Chucho came along to act as liaison. Some of the farmers were understandably unnerved seeing a hapless gringo stumbling around in their black-market gardens. But Chucho, in his early forties, was a wise guide. He always defused the tension with a swift joke, often at my expense.

Once, for example, when a jittery farmer asked how he could be sure I wasn’t a DEA agent from the States, Chucho said: “Because no agent would be stupid enough to come out here alone.”

Chucho was just one of at least 54 activists and community leaders murdered so far this year in the Golden Triangle, a major narcotics production zone in the northern neck of Cauca state. Eleven were killed within the last month, including an attack on Nov. 19 that left one dead and five more wounded.

Those numbers mean 2019 already has eclipsed last year’s body count, when 46 social leaders were slain within the Triangle, according to the Association of Indigenous Councils of Northern Cauca (ACIN). And that death toll is part of a larger, nation-wide trend. According to one independent study, 734 activists and community leaders have been killed across Colombia since 2016.

Chucho, like most of the other victims in Cauca, was a member of the indigenous Nasa people. He was also the founder and leader of a local NGO called the Avelino Ull Association, with a special focus on protecting indigenous rights.

“He stood up to them [the narcos], and they killed him for it,” says his widow, 28-year old Ceneida, when we sit down to talk on the porch of the same house on the outskirts of Toribíowhere I’d first met her husband four years ago.

The wave of killings has brought a Colombian military task force to this small, impoverished hamlet. Delegations from the United Nations, the Organization of American States, and Doctors Without Borders have come to Toribío as well, all of them staying in the town’s lone hotel and cruising its unpaved streets in their shiny white SUVs. Several large, illegal, cartel-owned marijuana plantations are clearly visible in the foothills that surround the town, but no one goes out there, least of all the soldiers.

“They’d already threatened Chucho,” says his wife, who was six weeks pregnant at the time he was killed. “The sicarios would call and send text messages saying not to speak out against them. Or else. But he always said he would continue the struggle,” Ceneida says. “He said he would fight them to the death.”

The Nasa are Colombia's second-largest ethnic group, and the ACIN network is made up of 22 communities, most of them rural towns and villages scattered throughout these lush foothills. The rich soil and sprawling, lawless wilderness are perfect for illicit crop cultivation, which is what gave rise to the Golden Triangle moniker, after the same term used for an infamous drug-producing region in Southeast Asia.

The Triangle—which produces an extremely potent, much-coveted, and oft-killed-for strain of marijuana aptly nicknamed “Creepy”—sits centered among the towns of Toribío, Caloto, and Miranda, smack in the middle of ACIN’s territory.

The Triangle is also home to a number of drug-fueled paramilitary crime groups, all of which are directly at odds with the Nasa cabildos, or leadership councils, a handful of NGOs like Chucho’s, and the insanely brave members of the Guardia Indigena, or indigenous guards.

Members of the Guardia have been particularly hard hit by the recent violence, as it’s their job to be the first line of defense for communities plagued by cartel attacks. They’re an all-volunteer force that routinely faces off against narcos and guerrillas, and does so without weapons. Using sheer force of numbers they’re known to seize drugs and guns, and then destroy those seizures in public ceremonies before the cabildos. They also sometimes capture cartel foot soldiers, who are then tried before the assemblies. (Indigenous justice for these captives can be severe, including public lashings and up to 40 years incarceration and “re-education.”)

And the Guardia accomplish all this armed with nothing but their traditional bastones—short, tasseled staffs believed by the Nasa to be endowed with spiritual powers. Instead of wearing Kevlar, as do their enemies, the guards wear simple blue tunics emblazoned with the Nasa words “Cxhab Wala Kiwe” (Land of the First People).

“The indigenous guards are self-protection mechanisms that these communities have developed over time [using only] presence and political solidarity,” Gimena Sánchez-Garzoli, director for the Andes at the Washington Office on Latin America (WOLA), writes in an email.

“For example, if a person is under threat by an illegal group, the guard will go to the area with some 50 indigenous people making it difficult for the actor to carry out the killing,” says Sánchez-Garzoli, who likens the Guardia to “the ‘Guardian Angels’ of the NYC subway in the 1980s.”

Unfortunately, solidarity, strength in numbers, and sacred staves are often not enough against automatic weapons. Such was the case on Oct. 29, less than a week before Chucho was killed, when five members of the Guardia, including a Nasa regional governor, were massacred in the village of Tacueyo, just a few miles outside of Toribío. Six other Nasa guards were wounded in that encounter. A few days after that, a group of four engineers and topographers were gunned down near Caloto while scouting a new roadway.

“The armed groups involved in the illicit economy want to rule our lands. They want to move drugs freely through our villages, and tell us where we can go and when,” said Mauricio Capaz, a regional coordinator for ACIN, when we met in the group’s headquarters in Santander de Quilichao, on the edge of the Triangle. (A few weeks after our encounter, last Friday night, a car bomb exploded in front of the Santander police station, killing two officers and wounding 10 more.)

Capaz went on to list several armed groups present in the Triangle, including the Army for National Liberation (ELN), and the People’s Liberation Army (EPL), both of which count on narcotics sales to fund their campaigns against the government.

Colombia remains the world’s top producer of cocaine, despite Washington’s insistence that Bogotá adopt a controversial, hard-core eradication policy. Meanwhile, the genetically modified Creepy species of cannabis now fetches farmers as much as 20 times more per pound than cocaine, making this “super weed” the crop of choice in the Triangle. It’s also a coveted source of revenue for a wide variety of underworld actors, who can sell the Creepy for up to $1,800 a pound on the U.S. market.

In addition to the guerrillas, Capaz says, there are also more “traditional” crime groups operating in the Triangle, with names like Pelusos, the Gaitanistas, Clan Golfo, and even Mexico’s Sinaloa Cartel, all of them madly sharking up the Creepy strain to ship it north to the U.S. by land and sea.

“But the most dangerous ones in the Triangle,” says Capaz, his voice instinctively falling to a whisper, “are los Disidentes,” the dissidents. This group, he tells me, is responsible for the massacre of the governor and her party, the engineers, and most of the other murders and acts of mayhem in northern Cauca over the last few years. According to Chucho’s family and other sources in the Toribío cabildo, they’re also the ones behind Chucho’s assassination.

“No one can challenge the Disidentes and get away with it,” Capaz tells me. “They kill all who get in their way.”

The Disidentes are a splinter group of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC). They are also known as the ex-FARC mafia. The FARC was a force of Marxist guerrillas that battled the Colombian government for over 50 years. The longest-running conflict in modern history cost some 260,000 lives, and left the country with 7.3 million internally displaced persons, the highest number in the world.

A peace agreement signed in 2016 was supposed to have ended the fighting, and thousands of guerrillas did demobilize as part of the accords. Many others, however, refused to lay down their arms. Only now, instead of fighting for leftist values and the rights of the poor, as their predecessors claimed to do, the FARC dissidents were concerned only with enriching themselves.

Comprised of some of the most battle-hardened and anti-social members of the old guerrilla force, the ex-FARC mafia quickly set out to take control of the Colombia’s underworld, but they continued to operate under the guise of classic FARC units and brigades to give themselves an air of legitimacy.

“Los Disidentes are FARC only in name,” says a source in the Colombian armed forces, who agrees to speak only on condition of anonymity. “The old FARC doesn’t exist anymore. These new guys are just pure narcos, and nothing more.” Unlike the original FARC, the new breed are “undisciplined and ruthless. They’re young, out of control. They only cause they follow is their own.”

Robert Bunker, a professor with the Strategic Studies Institute of the U.S. Army War College who specializes in cartel violence, describes the ex-FARC movement as a “commercial or criminal insurgency,” which has learned that “you can’t eat ideology.”

Bunker describes the Disidentes as a “21st century type of insurgency as opposed to mid-20th century Maoist or old-school political insurgency [like] the FARC. This new form of insurgency is all about materialism—getting money, power, and women—but also has an oblique political component. The leader of the band of brigands ruling the local town or plaza ends up becoming a ‘gangster warlord,’” Bunker says.

The most powerful warlord operating in Cauca today is Gerardo “Barbas” Herrera, commander of the dissident FARC’s Dagoberto Ramos Mobile Column of the Sixth Front. The massacre of Nasa Governor Cristina Bautista and four of her indigenous guards on Oct. 29 occurred shortly after they’d detained the 35-year-old Barbas and another high-ranking commander traveling with a handful of sicarios in a lone truck. A few minutes later, the armed forces source says, Barbas’ reinforcements arrived, surrounded Bautista and her men, and opened fire.

The killing of the engineers a few days later apparently happened because they refused to pay an extortion fee. They were executed to send a message to others who might resist control by the “Dagoberto Ramos Front,” says ACIN’s Capaz.

According to Bunker, the new breed of profit-first rebels are far more dangerous than their ideologically motivated counterparts: “Criminal insurgents are much tougher to contain and combat than old-school insurgents,” a model that is dying out.

That’s because, he says, “previous insurgencies existed and interacted primarily in state level economies,” while the criminal variety, “are tied into the globalized and predatory economy that has since emerged.”

Bogotá’s response to the series of massacres this fall in northern Cauca has been divisive, to say the least. After Governor Bautista and the engineers were killed, far-right Colombian President Iván Duque vowed to send an additional 2,500 troops into the Triangle. That surge doesn’t sit well with either local indigenous residents or international observers like WOLA’s Sánchez-Garzoli:

Duque “ordered the militarization of the area,” she says, “the one thing indigenous communities have shouted over and over does not work to protect them, but rather places them further in harm’s way and in the middle of combat operations between the different illegal groups.”

ACIN’s Capaz says that the Nasa, “don’t want any armed actors” operating on ancestral lands. “The narcos want to dominate our lands and treat us like slaves. But the government also wants to control our territory, and to access our natural resources for their own gain,” he says.

“The state wants to exterminate us, and our culture,” another Nasa governor tells me in Toribío, “but we’re not going anywhere.”

The U.S.-backed Colombian military has a long history of human rights abuses, including some 10,000 “false positives”—extrajudicial killings of civilians that are then claimed as insurgents to prop up a given unit’s body count.

Nasa authorities allege the army is responsible for two false positive cases in their territory within the last three months, including a human rights worker whose murder the army tried to pin on the Dagoberto Ramos Front. Another eight false-positive killings in a nearby district—all of them minors—prompted the resignation of Duque’s defense minister earlier this November.

Unfortunately, the violence in northern Cauca tracks with a general spike in killings of indigenous peoples and social leaders since Duque took office in 2017.

WOLA Director Sánchez-Garzoli attributes that in part to the fact that Duque has failed to implement the “Ethnic Chapter” of the peace accords between FARC and the government, which would have promoted crop-substitution programs aimed at replacing marijuana and coca cultivation on indigenous lands, while also strengthening and providing funds for Indigenous Guardia units.

In addition to walking back on promises made in the armistice, Duque has also persisted in vocally denigrating his country’s minority groups, including the Nasa, portraying them as “an obstacle to development,” Sánchez-Garzoli writes.

“This also degrades and dehumanizes ethnic minorities and stigmatizes them,” she adds. “It basically puts red targets on the back of ethnic groups in the eyes of illegal armed groups.”

Bunker, of the Strategic Studies Institute, agrees with Sánchez-Garzoli that the Duque regime’s strategy is off target.

“Colombia will gain no ground against Clan Golfo, Sinaloa, or the Disidentes until it addresses the underlying lack of economic opportunity and the chasm between rich and poor in its society, he says. “The rich—with their links to multinational corporations— have the formal economic markets locked up, so the poor have no choice but to ‘go criminal.’”

During our talks, Chucho had said what worried him most was that the children growing up in Nasa villages inside the Triangle would come to see drug cultivation as a normal way of life. And I understand his concern. The hills above Toribío are lit up each night like Christmas trees by hundreds of outdoor grow lights, while men openly smoke enormous joints of Creepy in the town’s unpaved streets.

“It is like a sickness among us,” Chucho Mestizo told me once, “and so the cartels rob us of a true future.” As part of his work, Chucho had been pressuring the national government to assist farmers with legal crop substitution programs within the Triangle, in accordance with the 2016 peace agreement.

On Nov. 3 of this year, in the wake of the recent massacres by Barbas’ outfit, Chucho and other NGO members gave speeches to the cabildo assembly, urging the village elders to stand up to threats from the Dagoberto Ramos Front. That same night, according to his wife, armed men surrounded the family home and ordered Chucho to come out.

“I begged him not to go,” says Ceineda, fighting back tears. Not only was she pregnant but the couple’s 4-year-old son was also in the house with them that night.

“He knew they could break in to get him if he didn’t go out,” she says. “And so they might’ve killed us all. He kissed me and told me not to worry. That everything would be all right. And then he gave himself up to save us.”

And so Chucho went out into the night. And spoke to the men who had come for him, although Ceineda couldn’t hear what he said. Perhaps he even tried to defuse the situation with a joke, as he had with the skittish coca farmers we’d met.

A few minutes later, Ceineda says, she heard three evenly spaced gun shots, followed by an extended burst of automatic fire. When Nasa neighbors arrived and found Chucho he was already dead, shot six times in the head and chest.

Ceinada tells me that in the days after Chucho’s murder by the ex-FARC’s next-gen insurgents she began to have severe cramps. She went to the doctor, and was told the shock of her husband’s death had claimed the life of their unborn child.

“I don’t know what to do now. We’re not safe here anymore,” she says, clutching her surviving son to her chest. “I just wish we could go back to the way things used to be.”