Devoid of the mockery that greeted its subjects upon their mass suicide in March 1997 (the largest ever committed on U.S. soil), Heaven’s Gate: The Cult of Cults takes a comprehensive look at the infamous millenarian outfit in order to understand how they came to be, how they came to their fatal end—namely, with numerous adherents castrated and everyone overdosing on phenobarbital and vodka—and, more fundamentally, how such groups operate, both in terms of attracting and indoctrinating devotees. Director Clay Tweel’s four-part HBO Max docuseries (premiering Dec. 3) is thus the fascinating story of a truly out-there collective that sought salvation at the tail of the Hale-Bopp comet, as well as an incisive examination of cult dynamics.

Although no matter the seriousness of its analysis, this non-fiction effort can’t fully change the fact that—courtesy of its own philosophy and behavior—Heaven’s Gate ultimately earned whatever ridicule and condemnation it received.

The infamous cult was founded by music teacher Marshall Herff Applewhite and nurse Bonnie Nettles, who met in 1972 when the former was treated by the latter at a hospital (for what one interviewee contends was a “psychotic episode”). Together, they came to believe they were messiahs whose teachings could help people physically transform into aliens, at which point they’d be able to board a spaceship bound for heaven (known as “The Next Level”). Their scripture was a combination of New Age philosophy and New Testament dogma, and with many 1970s Americans seeking fulfillment from alternate “religions,” they quickly attracted a following. In 1975, they became brief national news when, in Waldport, Oregon, they convinced 20 attendees at one of their seminars to “vanish” along with them.

Applewhite and Nettles went by Do and Ti (taken from The Sound of Music song), and “The Two” preached an ascetic way of life that involved strict obedience, the rejection of all earthly goods and relationships—especially with family and friends—the changing of names to six-letter monikers that ended in “ody,” the suppression of sexual urges, and the overarching notion that the end-times were fast approaching and that their conversion into celestial E.T.s destined for paradise was right around the corner. It sounds outright insane, and yet as Do and Ti’s travelling caravan of acolytes made its way across the country, living at camp grounds and subsisting thanks to the generosity of one member (who had a hefty trust fund), their ranks began to swell. Before long, they were making headlines as an up-and-coming little movement—attention that came with a significant degree of censure, such that Do and Ti eventually took their cult underground.

Through commentary from former members like Sawyer and Frank, as well as from sociologist Janja Lalich, religious studies professor Benjamin Zeller, and cult exit counselor Steve Hassan, Tweel lays out Heaven’s Gate’s insidious methods. Though many of its constituents came from stable homes and professional careers, the group was capable of getting its hooks into them by promising both order and contentment in a tumultuous world. At the same time, it played into their attraction to the unknown, the great beyond, and life’s grand mysteries via an ethos modeled after Star Trek. Also central to its allure was the idea of escape—from an unfulfilling society, an unsatisfactory former identity, and a corporeal body plagued by forbidden sensual acts.

Heaven’s Gate astutely points out that Do’s championing of asexuality—and castration, which is recounted in grisly fashion by Sawyer—stemmed from his own self-hatred regarding his homosexuality, just as the 1997 arrival of the Hale-Bopp comet provided Do with the prophetic “sign” he needed to motivate followers to go through with his final plan. Director Tweel shines an illuminating light on the group’s twisted manipulations and rationalizations, which became even more convoluted once Ti died of cancer in 1985, thereby disproving her and Do’s metamorphosis doctrine and forcing Do to continue onward with a revised version of their fate: now, they’d all exit their human forms (i.e their “vehicles”) to spiritually ascend to the “Next Level.”

Do’s canny response to this crisis (which Reza Aslan explains is a prototypical example of “cognitive dissonance”) let the “family” continue on its path. Tweel’s portrait of Heaven’s Gate benefits from candid first-person testimonials of Sawyer and Frank, and also the raft of home movies that Heaven’s Gate shot during its later years, replete with clips of Christmas parties, forums, and exit interviews in which zealous men and women, their heads shaved to enhance their androgyny, speak about their joy over finishing this phase of their journey. What emerges is an exposé of a carefully thought-out system designed to de- and reprogram susceptible individuals searching for a new self, a new start, and a new adventure.

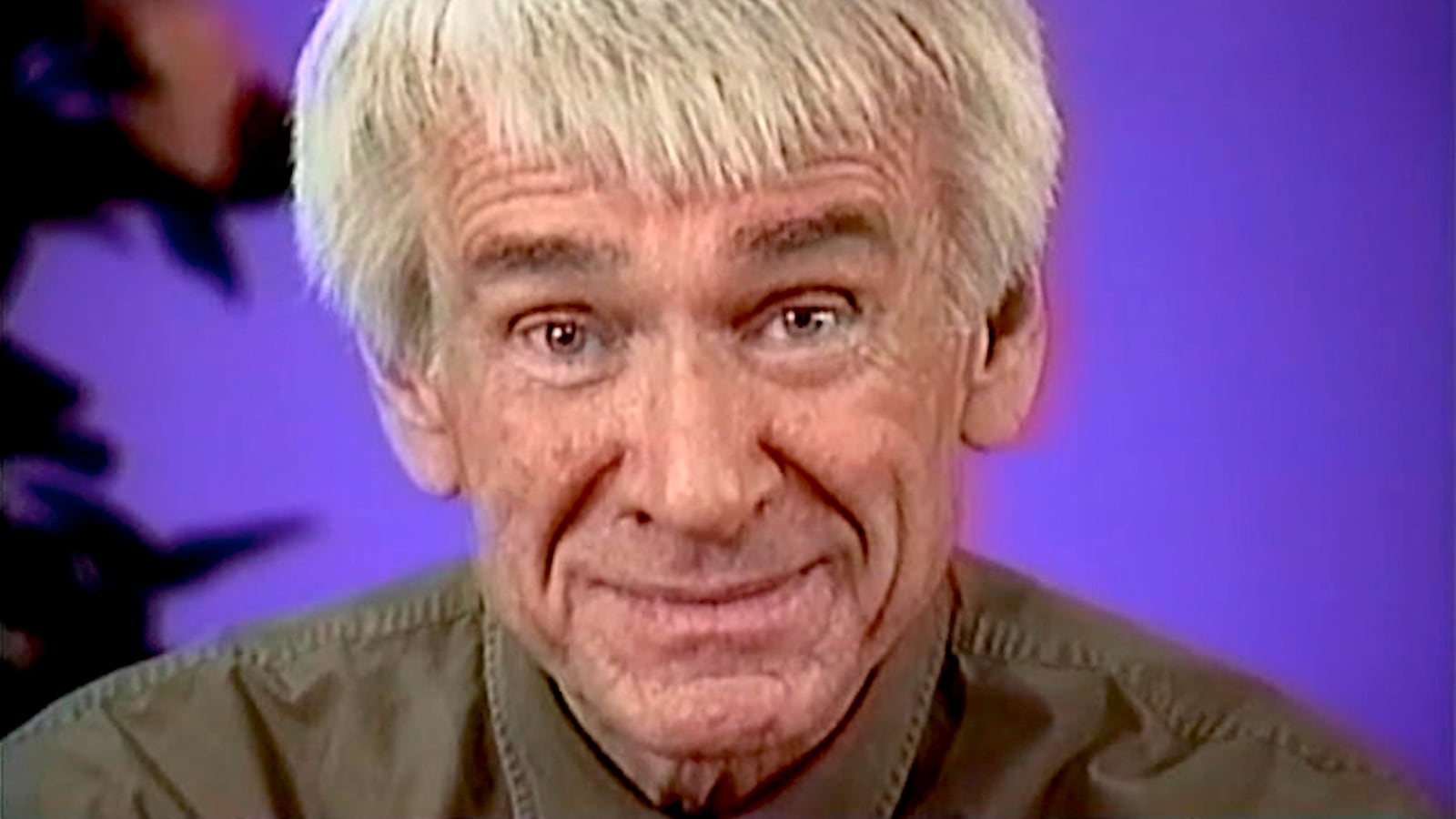

Members of the Heaven's Gate cult in Heaven's Gate: The Cult of Cults

HBO MaxWhile Lalich and Hassan suggest that anyone might have fallen under Do’s spell, that notion is contradicted by the fact that Heaven’s Gate failed miserably to attract fresh blood during the early ‘90s; in seminar videos from that decade, strangers are seen asking tough, skeptical questions, and often walking out rather than continuing to endure the hosts’ sci-fi nonsense. More persuasive is the series’ dissection of cults’ process of brainwashing through isolation, repetition, and peer pressure—the last of which compels people to go along with group attitudes even when they directly contradict obvious, verifiable reality (a phenomena borne out by the Asch conformity experiments).

Tweel’s sturdy formal approach mixes confessional talking head interviews and intimate archival material. It also involves swirling animated interludes that evoke the enlightenment-by-way-of-mutation nature of Heaven’s Gate’s beliefs, and which contrast sharply with the creepy VHS movies made by Do and his bald-headed disciples. Most unforgettable of all, however, is Sawyer’s late admission that, though he left his alien-obsessed brethren due to his inability to quell his carnal impulses (in other words, he couldn’t stop masturbating!), he remains committed to one day achieving transcendence and reuniting with Do and Ti—a revelation which proves that it’s far easier to escape a cult physically than it is mentally.