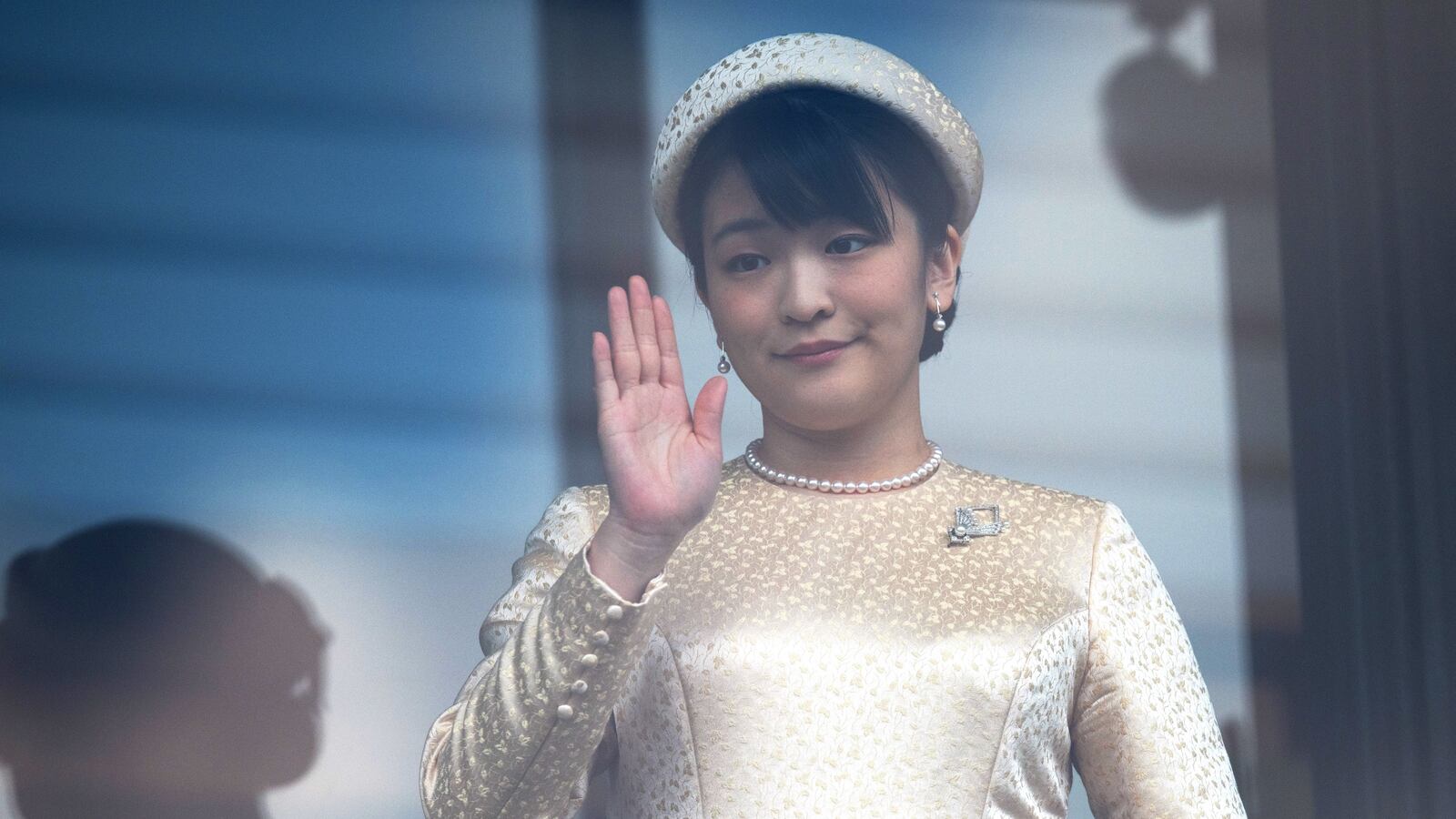

TOKYO—At long last, Japan’s Princess Mako and her “commoner” boyfriend, Kei Komuro, will marry on Oct. 26, after a three-year delay. But will they live happily ever after?

Yes, probably, if they follow through on their plans and get the hell out of Japan.

Opposition to the marriage by the general public, the press, and conservative politicians is strong. In an opinion poll taken by AERA magazine, 93 percent of respondents said they felt the marriage was nothing to celebrate. There have even been small street protests by elderly fanatics holding handmade signs that read, “No! Komuro,” “Do Not Pollute the Imperial Family With This Cursed Marriage.” And yet, Mako will not stand down.

It should have been a classic Japanese imperial fairy tale: Princess meets brilliant boy in college, they fall in love and get engaged. This would be followed by a lavish royal wedding. But now, thanks to Japan’s post-war constitution—which also stipulates that patrilineage is the imperial way—the princess must immediately be booted out of the royal family upon tying the knot. There will be no elaborate Shinto rituals to mark the wedding of these two lovebirds. The traditional ceremonies for imperial family members’ weddings have been called off, and the official meeting with the emperor and empress prior to the marriage will not happen.

In an unprecedented decision, Mako has refused to accept a $1.3 million dollar “consolation prize” for giving up the royal registry for love and marriage. The money comes from taxes and is meant to ensure the dignity of departing aristocrats. The Imperial Household Agency, which rules over the royals here like China rules Hong Kong, announced, after much debate, that they “will allow her not to accept it.”

No one in the Japanese press has had the temerity to ask the Agency, “Why do you even announce you’ve accepted her decision not to take the money? Were you going to stuff it in her suitcase, instead? Isn’t that her decision, not yours?” There are conservative scholars who argue imperial family members don’t have the basic human rights guaranteed in the constitution. These scholars are part of a loud contingent of people in Japan who oppose their marriage on dubious grounds.

At first, it seemed like everyone was happy for Princess Mako. In 2017, the two held a press conference to announce their unofficial engagement. The conference was held at the Akasaka East Palace in Tokyo’s Minato Ward. They appeared to be beaming, happy, and deeply in love.

That bliss did not last long. What went wrong?

Komuro and the princess met in 2012 when they were students at the International Christian University in Tokyo. Their wedding was initially scheduled to take place on Nov. 4, 2018, but before that could happen, a weekly magazine threw a wrench in their plans. In December 2017, Shukan Josei (Weekly Woman) reported what was considered a major scandal with the headline: “Imperial Family Shocked And Shaken, Komuro’s Mother Owes Money To Former Fiancé.”

The entire affair boiled down to this: Komuro’s mother and her former fiancé had money issues. The man claimed the mother and son had failed to repay a debt that was owed to him, of about $36,000. Not long after, both the tabloids and the mainstream were shamelessly reporting on the private life of the Komuro family. No mistake was too small, no rumor too unsubstantiated to be put into print. In the gutters of social media, some asserted that Komuro was actually Zainichi, Korean-Japanese. In Japan, the Korean-Japanese, many of whom are now fourth-generation residents, originally brought to Japan as slave labor, are often looked down upon and marginalized.

The Imperial Household Agency went into panic mode after the reports of financial trouble and other flimsy scandals kept flooding in. They announced in February 2018 that the ritual ceremonies were going to be postponed. They also pressured Mako to release a statement explaining why the marriage would be delayed. She reluctantly complied.

In August 2018, Komuro left for the United States to study at Fordham University’s law school. The two remained engaged but things looked bleak. A couple of months later, Mako’s father, Prince Akishino, held a press conference. He said it wasn’t feasible to host an engagement ceremony until the financial disputes were resolved. He implied that it wasn’t a situation where “the Japanese people could really celebrate the event.” He also told the press, “Recently, I have not spoken much with [Mako], so I don’t know how she feels.”

Mako responded to her father by releasing a statement in which she was adamant about her desire to marry her college love. She let it be known that she would wait for Komuro to graduate from law school and take the bar exam.

Mako and Komuro reportedly didn’t meet again in person until he returned to Japan in September. When he arrived at the airport, the mass media went agog over his new hairstyle: He had a ponytail! Clearly, this was a sign that he was unfit to marry into the proximity of the imperial family. One sports newspaper ran the headline, “Ponytail Returns,” and included a diagram of the offending hairdo.

A Japanese media outlet even decided that the haircut merited serious investigative journalism. While Komuro quarantined at home, he reportedly had his hairstylist come to the house and trim his long hair. Evening tabloid Nikkan Gendai concluded that getting your hair trimmed at home may be a violation of Japan’s Beautician Laws.

The amount of vitriol launched at Komuro is shocking to anyone outside of Japan. “The hate Komuro campaign stems from the sexism of a patriarchal order,” professor Jeff Kingston at Temple University, author of the seminal modern history text Contemporary Japan, told The Daily Beast. “They can’t tolerate women making their own choices and standing up to male authority. The shameless attack on his looks is not journalism. It’s institutionalized bullying with a green light from powers that be.”

In the end, Mako won’t get the lavish ritual send-off that some might have hoped for. She has opted for a low-key exit, including visiting the mausoleum of her great grandparents, Emperor Hirohito and Empress Nagako. At their graves, she reportedly informed them of her decision to get married to a commoner. Perhaps they would have approved.

She may have given up a million dollars to marry her beloved, but the princess did send a powerful “fuck you” to the powers that be in Japan. The diminutive princess is no weeping willow. With her marriage, there will be only 17 members of the imperial family left, and unless the rules change, the family will keep getting smaller and smaller and even risks fading into oblivion. The union has sparked discussions about changing the laws to allow women who marry commoners to remain in the imperial family.

Kaori Shoji, author and essayist, sees the opposition to the marriage as indicative of a generational divide. “The union seems to be a thorn in the side of people mostly over 60, who had long idolized former Empress Michiko. For the older generation of Japanese, Michiko-sama represents all that’s wonderful about Japanese womanhood: Marriage at an appropriate age for child-bearing, sacrificing her personal life completely in the name of upholding tradition, and supporting her husband for what is effectively an eternity.”

Princess Mako, on the other hand, “is not adhering to her grandmother’s model at all,” says Shoji.

“She’s both headstrong and sensitive, and has a will of her own. In short, she’s a modern young woman who wants nothing to do with the sacrifice and child-bearing BS that has defined the destinies of women in the royal household. She also seems to have no qualms about ditching her country, family, and lineage to be in New York with the man she loves.”

Princess Mako and Komuro have already made plans to move to New York City, where she will find work as an art curator, and where he already works at a law firm. “Marrying into royalty is a tough job,” Shoji says, “but someone’s gotta do it. And most Japanese are thankful it ain’t them.”