When Jose Luis Perez Guadalupe steps into Peru’s Miguel Castro Castro prison, the inmates greet him affably. They’re well aware that as the government’s most senior prison official he can order an unexpected search in the middle of the night and he can decide where they’ll serve the rest of their sentences. But they also remember his efforts in the tumultuous early 1990s that helped improve conditions at the prison. Thirteen years of volunteering as a pastoral officer at the chaplaincy appear to have helped create something of a bond between him and the prisoners.

“I like to talk to people. I speak to them and keep them calm,” says Perez Guadalupe. “They know that if they mess up, I will enter with full force.”

This is the man who has almost absolute control over the daily life of Joran van der Sloot, the notorious 24-year-old Dutchman accused of killing a 21-year-old Peruvian woman named Stephany Flores in 2010. Van der Sloot is currently incarcerated in Castro Castro. He is also suspected of killing Alabama teen Natalee Holloway in 2005 in Aruba, where he lived and where she was vacationing with high school friends. He was the last person to be seen with her; her body has never been found. Van der Sloot began something of a world tour, partly because his face and name were so well known and he was so widely reviled and suspected of killing Holloway. He ended up in Peru in 2010, drawn there by a large poker tournament. In Lima he met Flores, who also liked gambling. Van der Sloot was arrested in Chile days after the discovery of Flores’s battered body in his hotel room in Lima. He was quickly handed over to the Peruvian police. Since then, Castro Castro has been his home.

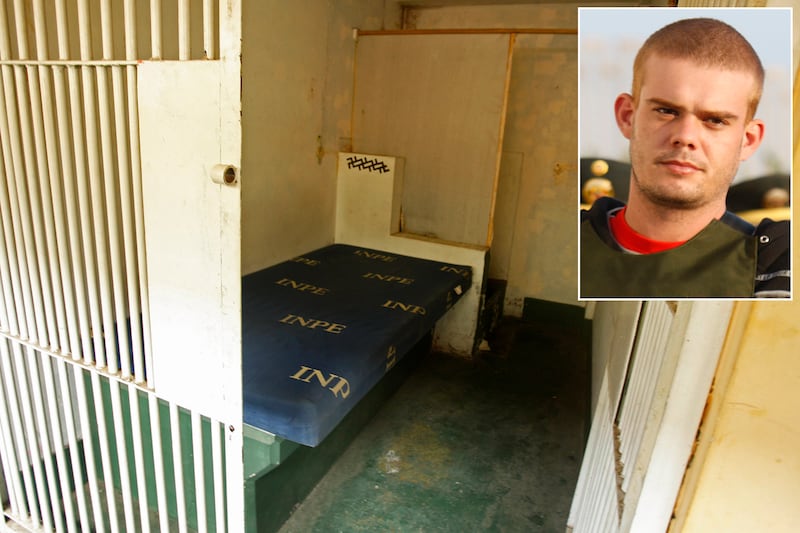

The prison, in the Lima neighborhood of San Juan de Lurigancho, was built to hold 1,142 prisoners, but the latest head count was 1,875, a reminder of the massive overcrowding prison authorities face. Van der Sloot is one of five inmates who occupy their own wing—a special place for the most hated, and most at risk, prisoners.

According to two sources who spoke on the condition of anonymity, van der Sloot is addicted to video games, and uses cocaine that keeps him up at night. Perez Guadalupe would not confirm those reports.

Perez Guadalupe’s recent appointment may have ended van der Sloot’s alleged happy days. “He’s in this area with four others,” says Perez Guadalupe as we ascend to the second floor of a small block of cells. I enter the area where van der Sloot currently lives. It consists of two sections. There’s a small kitchen counter on the right where inmates can store and prepare food. There’s a door that leads to a small bathroom. A gate opens into a hallway, where the five cells stand in a row.

Perez Guadalupe refers coolly to Van der Sloot as “uno más”—just one of the 53,000 people imprisoned in Peru. But in truth, Van der Sloot is not just another inmate. The new prison boss, only four months into the job, recites the Van der Sloot plan like a well-memorized poem: “He will endure his trial in these present conditions and once he is sentenced, the decision will be made” on where to house him.

Perez Guadalupe, a criminologist, sociologist, and theologian, has brought a disciplined hand to Castro Castro. About a month ago, he launched a general search in the middle of the night. In the carefully planned operation his handpicked team of 300 confiscated five guns and 141 cell phones.

As we walk down the hallway of van der Sloot’s cellblock, an Asian man waves hello from just outside one of the cells. A Mexican they call Don Pepe is his neighbor. It’s noon and it’s bright outside, but Van der Sloot’s dim burrow reeks of human sweat and the heavy breath of oversleeping as improvised drapes made out of bedclothes hang from the bars. Van der Sloot’s cell was located at the end of the hallway; Perez Guadalupe would not allow me to get too close.

Perez Guadalupe explains that van der Sloot is in a Closed Type A Regime—maximum-security—and new locks have been installed on the three gates that separate him from the main prison area. “We’re not so worried about what he can do to others, but really, we have to take care of him, so others don’t harm him,” he says. Van der Sloot may have gone from being the hunter to becoming the hunted. Rumors abound of people who wish to take revenge for Flores’s death.

“So, I have to make sure no one comes near him, not a fellow inmate, nor a penitentiary employee, nor any visitor,” says Perez Guadalupe. “Many things may have happened before I arrived, but I can only be held responsible for what goes on during my administration. I’ve had his cell searched, but I can’t tell you what I’ve removed.”

Inmates in Castro Castro can generate income in the prison’s workshops by crafting ceramics, among other items, which are sold in craft fairs throughout the country. They can also work in the prison bakery.

Convicts can also work from their cells, as van der Sloot does. His attorney, Jose Jimenez, said in a recent interview that van der Sloot makes rosaries and crafts silver necklaces and bracelets.

The prison has long been riddled with corruption. Castro Castro employs 120 guards on a monthly salary of between $300 and $450 per month to handle the 1,875 prisoners.

“I can’t deny there’s a problem,” says Perez Guadalupe, who has created an anticorruption board in the prison system. “We are bringing order into the penitentiaries because the inmates dominated them or they were in cahoots with the guards. They’d pay the guards off to enter and keep televisions, among other things.”

A few months before Perez Guadalupe started the job, local Peruvian media reported that van der Sloot was enjoying privileges behind bars. According to the Flores family’s attorney, Edwar Alvarez Yrala, a young woman named Leidy Figueroa Uceda had gone to visit the prison and is now the mother of a child conceived with van der Sloot. Born in late March, the baby boy would have to have been fathered during van der Sloot's early days in Castro Castro. Figueroa, 22, appeared on local television stating she simply went to visit a family member at the prison; she denied having a relationship with van der Sloot. As did van der Sloot’s former attorney, Maximo Altez, who also denied the link between Figueroa and van der Sloot. “She is willing to take a DNA test and I’m sure Joran is, too. He is not the father,” said Altez in a report on Peruvian television, Channel 5.

Figueroa lives and works near the prison. According to reports, she works at one of the many kiosks that offer all sorts of commercial services, from renting skirts to the women who visit the prison on Wednesdays and Saturdays, to delivering food and cleaning supplies to the inmates.

The story of van der Sloot’s prison love-child does appear to be nothing more than gossip: according to the National Penitentiary Institute, Figueroa had entered the prison on two occasions to visit two other inmates who have now been transferred to other prisons. “He [van der Sloot] is contained in a restricted area under a closed regime that does not allow visits from nonblood relatives,” says Perez Guadalupe.

Next door to Castro Castro is a monster penitentiary named Lurigancho, which holds more than 6,000 inmates. Van der Sloot’s trial is scheduled to begin at 10 a.m. on January 6 in a courtroom inside the Lurigancho complex.

If he is convicted, van der Sloot will likely spend many years getting used to his own company. “Because of the nature of his crime and his special situation,” says Perez Guadalupe, “we can’t risk having him go into the ceramics workshop or the bakery, so whatever he does, will have to be from within his area.”