When four-star Gen. Stephen J. Townsend found himself in a financial bind while deployed overseas in 2019, he did what any top commander in the U.S. military would: get on Facebook to contact a 74-year-old widow he had never met before.

Townsend, a well-respected military commander who headed up the U.S. Army’s Africa Command (AFRICOM) until August, told the widow his “portfolio” had been held up by customs officials demanding large fees to release it. Could she help?

Such an overture would be immediately obvious as a so-called romance scam to most. But it apparently didn’t seem so far-fetched to the woman, a U.S. resident who is identified only as “N.W.” in a criminal complaint unsealed Friday in Salt Lake City federal court and obtained by The Daily Beast. Still, N.W. had questions—all of which “Townsend” was eager to explain away.

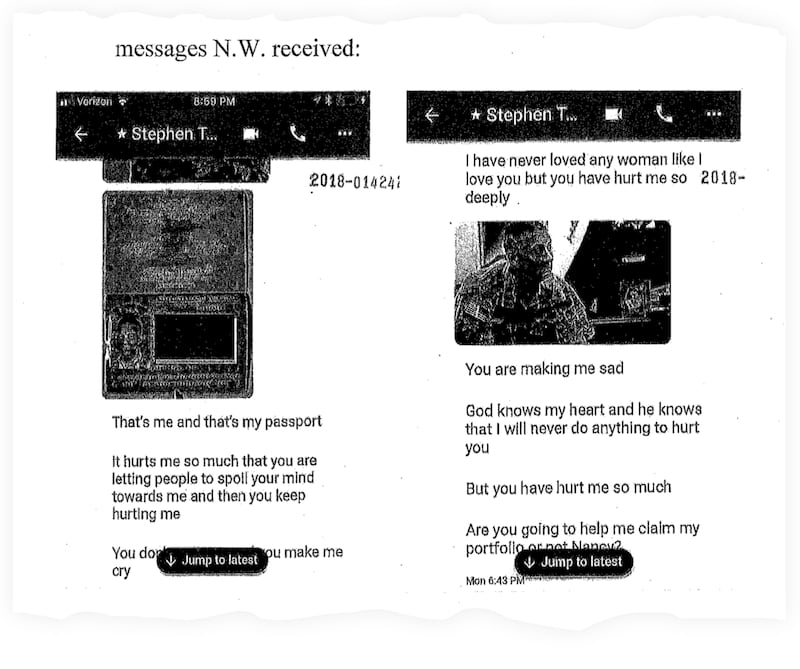

“That’s me and that’s my passport,” he wrote to N.W. on Facebook Messenger, sharing a photo. “It hurts me so much that you are letting people to [sic] spoil your mind towards me and then you keep hurting me.”

He continued: “I have never loved any woman like I love you but you have hurt me so deeply. You are making me sad. God knows my heart and he knows that I will never do anything to hurt you. But you have hurt me so much. Are you going to help me claim my portfolio or not Nancy?”

Townsend’s identity, for some reason, has been usurped by online scammers to such an extent that the U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC), which the general led from 2018 to 2019, felt compelled to issue a public warning in 2018.

“***IMPOSTER ALERT*** Gen Stephen J. Townsend, TRADOC CG, is NOT on Facebook, Twitter, Skype, Instagram, Google Hang Out [sic], dating sites, chat rooms, etc,” the statement said. “Below are examples of impostor accounts, these impostors attempt to harass & scam individuals. If you find one, report them!”

Reports of fraudsters misusing Townsend’s name began to emerge around 2014, when he was the commander of Fort Drum in New York State. While military personnel have long been targets of identity thieves and scam artists, it is unclear why Townsend became so popular among members of this particular underworld. A footnote in the complaint unsealed Friday says simply, “The proliferation of scams using General Townsend’s name and image has been reported by public sources.”

However, Townsend’s name has only shown up in a small handful of federal prosecutions, with most only referring to “a military commander” in court filings. Last year, a married woman in Pennsylvania lost $305,000—her family inheritance—to a “Townsend” she met playing Words With Friends 2. The case went cold, and cops don’t think the victim will ever get her money back, according to local reports. In 2020, a trio of scammers in Missouri were indicted on fraud and identity theft charges for their part in a romance scam using Townsend’s name. The three are now serving sentences in federal prison.

In N.W.’s case, the bogus Townsend instructed her to send checks totaling $140,150 to a group of men in Vineyard, Utah, who kept some of the money and transferred some of it to various bank accounts in Nigeria. Two of the men are now in federal prison. (An indictment filed in 2019 didn’t identify Townsend by name, but as a U.S. general with the initials S.T.)

A third, Chukwudi Kingsley Kalu, pleaded guilty late last month to one count of conspiracy to commit money laundering. A U.S. District Court judge ordered Kalu to pay $8.4 million in restitution, and seized his 2013 Lexus GS 350 and a $1.7 million house in Houston, Texas. Kalu still owes $7.2 million to the government, his attorney, Trinity S. Jordan, told The Daily Beast on Monday.

In the complaint unsealed Friday, which remained under wraps until the feds could make necessary redactions, the scammers, again acting as Townsend, are accused of extracting some $50,000 from a second widow identified only as “S.L.”

After contacting her on social media, “Townsend” told S.L., who was 75 at the time, that he was in Syria “but he couldn’t get military transport out,” according to the complaint.

“He told her he needed $50,000 to fly out on a jet specially equipped with bomb or missile detection,” the filing states, adding that the ersatz Townsend directed S.L. to send the checks to two men in Utah who were part of the same ring as Kalu.

The group didn’t restrict themselves to Townsend, the complaint says. They also masqueraded as an engineer working for an oil company in Oman, a Houston man under house arrest in Sweden over a tax debt back in Texas, a businessman working on a sewer project in Turkey, and a U.S. Army brigadier general with the initials “G.G.”

Kalu’s role was to deposit a portion of the funds in U.S. banks, after which it would be distributed among the rest of the crew. In a December 2017 phone call with American First Credit Union, Kalu told a customer service rep that the money he was receiving came from family members who were investing in a construction project in Nigeria, according to the complaint. The following year, the complaint says a woman in Michigan went to a KeyBank and attempted to deposit money into one of Kalu’s accounts, telling suspicious bank employees that the funds were for “her husband’s attorney.”

“The accounts to which he sent much of the money were, according to two co-conspirators, for purposes of a clothing business or a diesel oil shipping business,” the complaint states. “These three explanations—diesel oil shipping expenses, clothing business expenses, and construction project expenses—are simply not compatible.”

According to prosecutors, Kalu entered the United States on a student visa and lived in Orem, Utah from April 2016 until sometime in June 2019.

“In the 21 month period from August 2017 to May 2019, Kalu held accounts at six different financial institutions, where he deposited $950,000, including $328,000 in cash and $465,000 received through wires,” states a detention memo filed last July. Of that, according to the memo, he sent roughly $470,000 to accounts in Nigeria and withdrew about $150,000 in cash. But when two of Kalu’s co-conspirators were arrested on June 4, 2019, he was nowhere to be found.

A warrant for Kalu’s arrest was issued by a federal judge that August. In October 2019, the FBI was notified that he had applied for a job in Canada, the detention memo says. Kalu was apprehended by Canadian police and deported “for serious criminality and organized criminality based on the U.S. charges,” according to a May 2022 filing in the Ontario Court of Appeal.

Kalu and his common-law wife had arrived in Canada in June 2019, and both claimed refugee protection, the filing states. But while he was being forced to leave, Kalu’s baby daughter and wife, who was granted protected status in April 2021, were permitted to stay.

Kalu fought the move, arguing in court that “the risk of systemic racism in the U.S.” would prevent him from getting a fair trial, that “his life would be put at risk were he to be extradited to the United States and eventually deported to Nigeria,” and that his extradition would have a “devastating impact” on his family “because of their health and financial circumstances.”

After receiving assurances from the U.S. Department of Justice that Kalu would be treated fairly, and rebutting his claims that he would be persecuted in Nigeria and that his wife and child would be left destitute, a three-judge appeals panel ordered him deported. Kalu was re-arrested in Toronto on June 30, 2022, and was arraigned in a Utah federal courtroom on July 5.

Kalu is set to be sentenced on March 6. He faces a maximum of 20 years in prison.