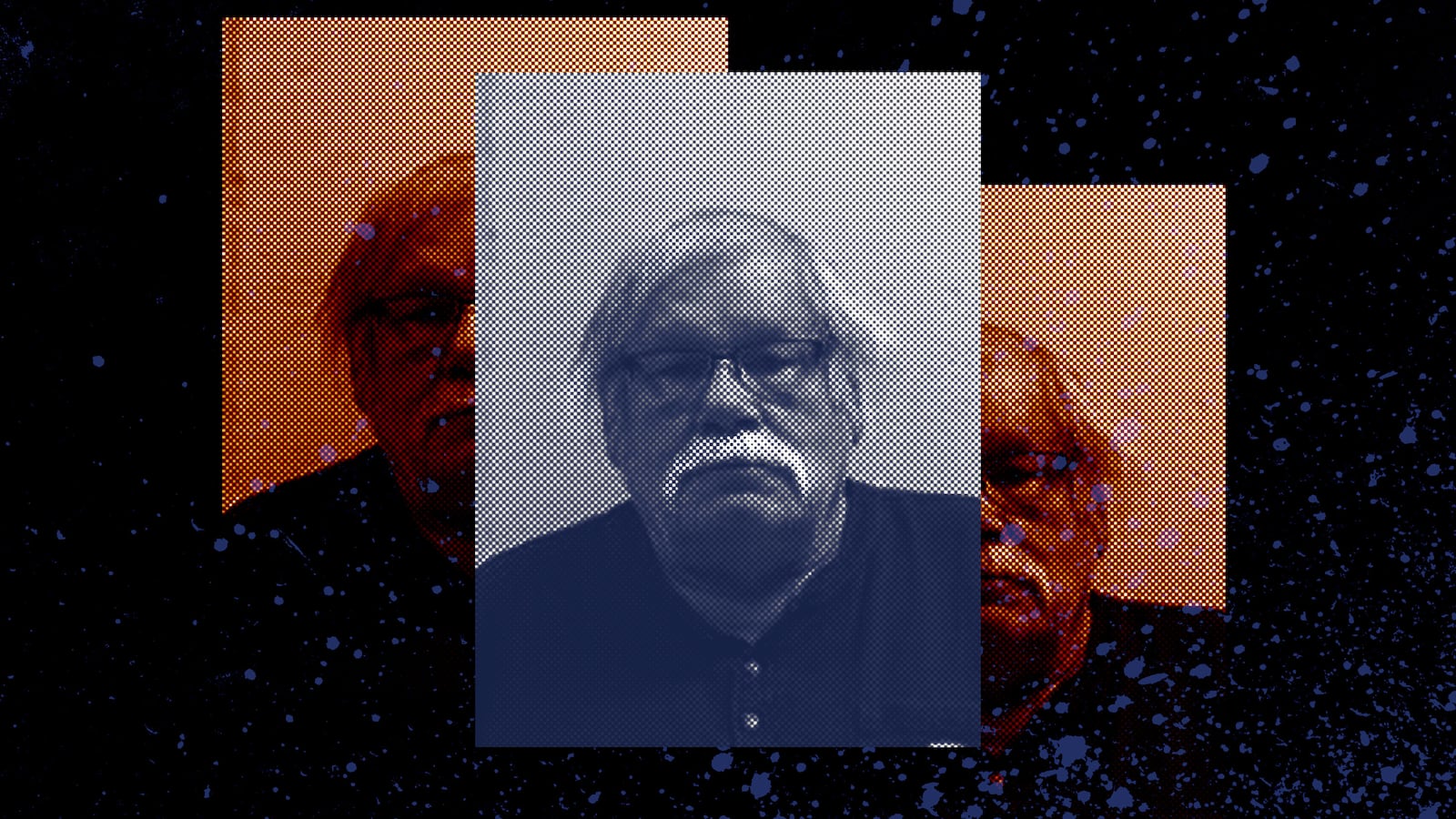

In his LinkedIn profile picture, Gale Rachuy looks like a fun grandpa, with a big white handlebar mustache and a wry smile. The 72-year-old poses in front of shelves of law textbooks, and lists himself as the CEO of Midwest Legal Service, based in Duluth, Minnesota.

But Rachuy is not and never has been a lawyer, according to an indictment filed against him in mid-December. Law enforcement say Rachuy posed as an attorney who had operated his own firm, and swindled at least one client out of $2,500. He is charged with one count of wire fraud.

This isn’t Rachuy’s first rodeo. He is the “epitome of a white-collar career offender” who has been committing acts of fraud and deception for more than 40 years, according to a judge who sentenced him in 2012 for interstate transportation of a stolen motor vehicle.

He has been charged in at least 56 criminal cases since the 1970s, including more than 90 counts of theft and swindling in Minnesota, according to the Duluth News Tribune.

For the last 44 years, Rachuy has not managed to spend more than a year out of his life outside of prison, according to incarceration records viewed by The Daily Beast.

Nonetheless, he maintains he is not a fraudster.

“I’m not (a con man),” Rachuy told the Duluth News Tribune in an interview from jail in 2011. Or if he was, he said, “I’m not a very good one.”

Although he has spent much of his life behind bars, Rachuy has never stopped fighting the authorities that put him there. With his self-taught legal knowledge, Rachuy has filed at least 113 suits of his own, the newspaper found, as well as around 50 federal suits, often against law enforcement officials, victims and prosecuting attorneys.

He blamed a crooked justice system for his lifetime of convictions, telling the newspaper that he was the victim of an organized effort by local and federal law enforcement to keep him in prison.

“It’s your past that keeps convicting you,” he said.

Law enforcement officials disagree.

“He’s definitely a problem,” St. Louis County Sheriff Ross Litman told the newspaper in 2011. “History has shown that even locking Gale Rachuy up behind bars doesn’t always achieve what the public would like to see.”

Gale Rachuy was 23 years old when he received his first criminal conviction. It was 1973 and he was found guilty of offering a forged check. It was the beginning of a lifetime spent in and out of jail.

In 1990, while being held in St. Louis County jail on charges of felony theft for failing to pay for business machines delivered to him by two stores in Duluth, he allegedly ordered $11,000 worth of furniture over the phone from a dealer. Rachuy arranged for it to be delivered to a property in Duluth, but told the furniture dealer he couldn’t be there to receive the furniture in person as he was tending to his ailing mother, according to a report in the Star Tribune that year.

The salesman happened to read a newspaper story about Rachuy’s other swindling charges and realized he was probably being conned. At the time, Rachuy was awaiting sentencing on theft convictions stemming from false promises to build log houses, and was facing further theft charges in two other counties.

The dealer called then assistant county attorney, Vern Swanum, who told him there was no way Rachuy could receive the furniture. “He’s sitting in jail right this minute!” Swanum told him over the phone.

Aerial view of Minnesota Correctional Facility, Oak Park Heights.

United States Geological Survey/Wikimedia CommonsBy that time, Rachuy had already become infamous in his home state. While being held at the Minnesota Correctional Facility at Oak Park Heights, he petitioned to change his last name to “Johnson” but a trial court denied his request, according to the Duluth News Tribune.

“He stated he thinks his name is famous because of his criminal record and that there isn’t anyone ‘in this system in Minnesota that doesn't know’ him,” a Court of Appeals opinion found.

By 1997, Rachuy told a reporter from the Star Tribune during an interview from Stillwater prison that he had already spent 30 of his 47 years behind bars.

That same year the state banned smoking in prisons, and Rachuy was part of a small group of inmates who tried, and failed, to bring legal action to stop the ban. Rachuy told the newspaper he was going through intense nicotine withdrawal, but that prisoners had stashes of cigarettes hidden all over the prison.

After his release from prison in 2000, Rachuy continued to commit crimes. From that year onwards, he was convicted of forging checks, and multiple counts of theft by swindle.

When Ross Litman became Sheriff of St. Louis County in 2003, Rachuy was a well-known figure among law enforcement. He had been posing as somebody working for a legitimate bail-bond company, Litman told the Duluth News Tribune.

“It’s been a history of this guy pulling some kind of scheme,” Litman said at the time.

It was in 2005 that Rachuy was first convicted of “unauthorized practice of law.” He had been practicing law under the business name Midwest Legal Services, issuing business cards and retainer agreements, and sending out invoices to clients, according to an evidence list viewed by The Daily Beast.

Over the next five years, Rachuy lived under the scrutiny of state and federal law enforcement, cycling in and out of prison. At times he was operating a lumber business, but authorities suspected he was also engaged in criminal activity. In 2006, he was being investigated for “an alleged pattern of criminal behavior” by police in Minnesota and Wisconsin, according to court documents viewed by The Daily Beast.

In May 2007, Rachuy was imprisoned on several counts of check forgery and one count of theft by swindle. Prosecutors at the time said Rachuy deposited three forged checks, totaling more than $100,000, into an Anchor Bank account in North St. Paul, according to St. Paul Pioneer Press.

Once again, Rachuy refused to accept the sentence handed down to him by the courts, instead taking the law into his own hands.

He appealed his conviction, representing himself and arguing that he had been denied his constitutional right to counsel. The conviction was overturned.

When Rachuy was retried on the same charges in 2010, he pleaded guilty to all counts and was sentenced to 50 months in prison. But two years later, Rachuy appealed the conviction again, saying the police had destroyed evidence in the case. The district court denied his petition. Again, Rachuy appealed that decision, but it was upheld by an appeals court, according to a court document viewed by The Daily Beast.

As he was being retried on the check forgery charges in 2010, Rachuy was up to his old tricks.

That summer, Rachuy went to Duluth Lawn and Sport and picked out a utility vehicle, mowers, a leaf blower, trimmer and a lawn tractor and arranged to have them delivered to his house, according to court documents viewed by The Daily Beast. Rachuy paid the delivery driver with a check for over $14,000 which bounced because the bank account had been closed two months earlier.

During the three-day jury trial that followed, Rachuy represented himself. On May 12, 2011, he was found guilty of issuing bad checks and was sentenced to five years in prison under the state’s “career criminal” statute, which allows longer sentences for defendants with a history of criminal activity.

Rachuy was defiant in an interview after the trial with the Duluth News Tribune. He planned to appeal the conviction, he said. When asked what he planned to do if he won the appeal, Rachuy told the newspaper: “I’m going to let you taxpayers pay for me for the rest of my life.”

The reporter asked what he meant. Rachuy was vague.

“I hope… I never get out of jail,” he said. “What for? To turn around, and have more charges brought against me?”

As soon as the case wrapped, Rachuy faced trial in Wisconsin on federal charges of buying vehicles with bad checks and transporting them across state lines to sell.

Rachuy pleaded guilty and was sentenced to 7.5 years in prison—the longest stretch he had ever served.

The hefty sentence did not seem to deter him.

While on some form of release in 2017 from federal prison, Rachuy was once again convicted of issuing bad checks. On July 8 and 9, 2017, Rachuy bought goods from the Midwest chain store Fleet Farm, totaling almost $1,300, paying with checks that bounced. Rachuy was sentenced to 90 days in jail.

Rachuy was released from federal prison in May 2020. For a short period, he avoided any criminal convictions. Instead, he filed suits against others.

The following year Rachuy sued his landlords for fraud in district court. He alleged that the men misrepresented the rental in Morgan Park, Minnesota, as habitable, when in fact it had been condemned. In his suit Rachuy says he would not have moved in had he known.

The suit also accuses one of his landlords of entering the building with Rachuy’s consent, and unplugging a freezer containing large amounts of seafood, including 120 trout, four lobsters, eight pounds of shrimp and 40 walleyes, all of which spoiled. Rachuy claimed the seafood was worth more than $1,640.

Rachuy also claimed that the landlords had failed to secure the doors of the building, and that he was robbed multiple times, losing $5,000 in canned goods and a collection of 800 Zippo lighters that Rachuy says were worth $20,000.

That lawsuit was still making its way through the courts when Rachuy was arrested for his latest criminal escapade.

From March 2022, Rachuy was advertising himself as a lawyer, according to an indictment filed in federal court. He claimed to potential clients that he had been operating his firm, Midwest Legal Service, for 38 years, and employed seven attorneys. In fact the firm was a fraud designed to enrich Rachuy, prosecutors allege. One victim paid Rachuy a retainer of $2,500 for help with a post-conviction proceeding, according to the documents.

Although the victim is not named in the indictment, the story is consistent with one given to the Duluth News Tribune by James B. Mitchell, of Fayetteville, Arkansas. Mitchell hired Rachuy and paid the initial deposit, but then became worried he was being scammed, he told the paper. Rachuy never delivered the promised legal paperwork, nor did he refund Mitchell’s initial payment.

“He lies to his victims that he is an attorney when, in reality, he has never even graduated from any law school, and his only legal knowledge has been acquired by spending time in law libraries at the numerous federal and state prisons he has been incarcerated at over the course of his whole adulthood in the past 50 years,” Mitchell told the newspaper.

Rachuy is charged with one count of wire fraud. He is being held without bond in the Douglas County Jail. Attempts to reach Rachuy in jail were unsuccessful.

Over a lifetime spent in and out of prison, serving time hasn’t deterred 72-year-old Rachuy from continuing to commit crimes. He has spent almost 50 years of his life tied up in the criminal justice system.

Rachuy now faces up to 20 additional years in prison for wire fraud. He could be 92 years old before he is released and has a final chance to mend his ways.