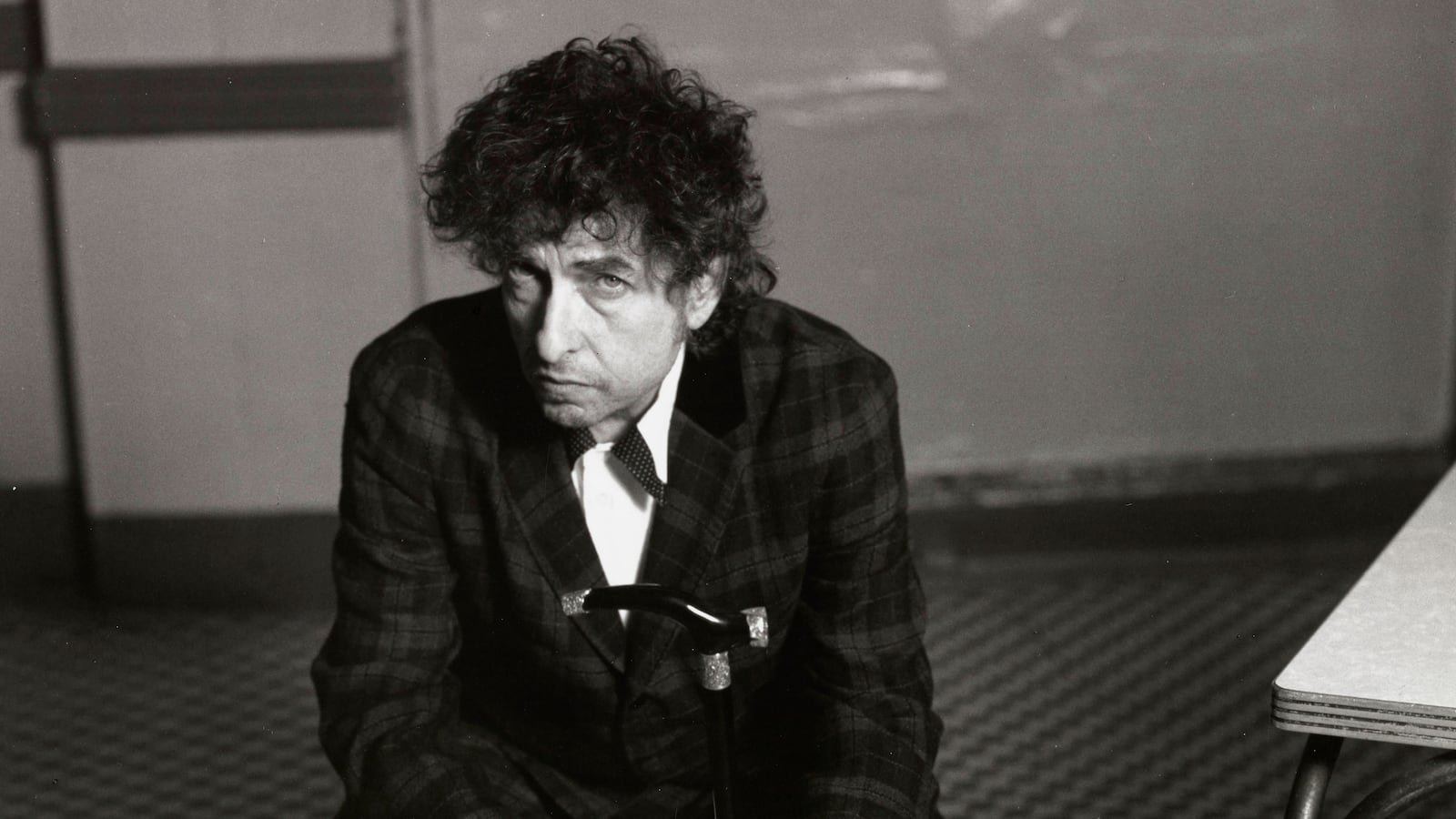

“Creative ability is about pulling old elements together and making something new,” Bob Dylan told me last month. “You have to have a vivid imagination.”

By the end of the 1990s, however, he was largely seen by the general public as a spent creative force; one whose vivid imagination had been dimmed by time and disillusionment. Dylan’s concerts, always real-time explorations of his restless creativity, were increasingly demanding for the more casual fan and had become the bastion of his diehards. And his albums, once greeted as manna from on high, were now—after what was perceived as a patchy 1980s and early ’90s, save for his tenure in the Traveling Wilburys—mostly being ignored.

But Time Out of Mind, released in the fall of 1997 and out now in a reimagined and expanded edition as part of Dylan’s long-running Bootleg Series, changed all that.

“Time Out of Mind,” Dylan once said, “was me getting back in and fighting my way out of the corner.” He’d written the bulk of the record—which begins unhappily, if hopefully, and ends on a bleak, desperate note—while snowed in at his Minnesota farm during the winter of 1996. To bring the songs to life, he called on Daniel Lanois, who’d produced albums for the likes of U2, Emmylou Harris, and Willie Nelson, and who had worked with Dylan almost a decade prior on 1989’s Oh Mercy. Feeling as though their creative partnership was unfinished, Lanois approached the project attempting to illuminate the dark, brooding, modern blues Dylan heard in his head.

But this would be the first album of original material from the musician in seven years—a time during which many people, including Dylan himself, wondered if he’d ever write a song again, let alone a great one. Still, if the archives at Tulsa’s Bob Dylan Center—the living, breathing repository of Dylan’s art, in all its many forms, that opened last May—are any indication, those fears were misplaced. Covered in Dylan’s spider-like scrawl, pages of furiously edited yellow legal pads teem with unused lines, verses, and even full pages of the discarded ideas that would eventually come to form Time Out of Mind.

Many of these can be heard in the more than 50 tracks included on Fragments: Time Out of Mind (1996-1997), the 17th entry in Dylan’s Bootleg Series. If, as Dylan has often said, a song is a living thing, Fragments, out on Jan. 27, helps tell that tale. At its center is a remix of the original 11-track album, a reimagining that retains Lanois’ swampy, ethereal feel while placing Dylan front and center and elevating the stories he told on Time Out of Mind in new and often surprising ways.

As Dylan once said, “It used to go like that. Now, it goes like this.”

Below, producer Lanois and engineer Mark Howard recall the fraught but miraculous birth of Time Out of Mind, an album that went on to win three Grammy Awards, including Album of the Year, and re-established Dylan as the preeminent songwriting force of the 20th century—but that, as you’ll learn below, almost never saw the light of day.

Daniel Lanois: I always go into projects thinking, “Maybe we could do something that hasn’t been done before.” I felt that way with Dylan. I felt that way when we did Oh Mercy 10 years before Time Out of Mind—I had a vision for it. For Time Out of Mind I had a vision, too. I wanted to make sure that you could hear every nuance of every word and that Bob’s voice sounded as beautiful as it could.

Mark Howard: Bob had done a show for the Atlanta Olympics, at the House of Blues, and it had been recorded. We got a call to see if we’d be interested in mixing it. So while we were mixing it, Bob would come in and listen. And just as we were getting to the last song, he turned to me and said, “Do you think you can make the harmonica sound more electric?” It sounded kind of plain, so I ran it through a little Tube Screamer distortion pedal, into a little amp, and then printed it back on the track. But the thing about it was, as soon as he stopped playing the harmonica, he started singing, so that sound that I put on the harmonica was also on his voice. He loved it so much, he said, “I want you to put that on all the songs.” That was the germ of the sound for Time Out of Mind.

DL: Time Out of Mind was started and finished in an old Mexican theater in Oxnard, California. A very unlikely location.

MH: The studio was this old 1940s Mexican porno cinema that I had turned into a studio; taken all the seats out and built a huge stage in the middle. We had grand pianos, organs, everything in there, and it was all mic’ed, so anywhere you sat down and played any instrument, I could be recording you that second without you knowing it.

DL: Bob talked about how he loves certain rock ’n’ roll records from the past, from Charlie Patton on up. I listened to a bunch of those records and I thought, OK, I see what Bob’s talking about. Those works were at the front end of the medium, [which] always offers excitement and discovery. And he wanted discovery to be part of this body of work. So I put the thinking cap on, “How am I going to do that now? Can we make a record that’s greasy and dripping in sweat?” But it had to go someplace. It had to go to the future somehow… I went to Manhattan and visited my friend Tony Mangurian, [who’s] a good drummer. I said, let’s hear you play on top of some of these old records that Bob loves.

MH: Bob came in and played the beginnings of “I Can’t Wait” on the piano. It was a gospel-style piano version. At the same time, Tony Mangurian [is] doing this hip-hop beat with him. It was really cool-sounding. After that session, Bob said, “I’d love to make a record like that kid Beck.” Odelay was out and he liked the way it sounded. We thought that would be a really cool angle for Bob. And so in Oxnard, we thought that we had the bones of the beginnings of the songs.

DL: Bob wanted to have more of an orchestra around him. He had 11 people in the studio at a time. And I respected that, because I knew that he didn’t want to make Oh Mercy again, and I didn’t either. We were standing on the rock of the blues, but how do we take that to the future? We’re going to take that to the future lyrically, for sure. So I did my best to do that sonically for him as well.

MH: Bob said, “I drive in every day, up the coast from Point Dume. Before I come out of Malibu into Oxnard, there’s a stretch where this kind of pirate radio station comes on, and it’s all old blues. Those records sound amazing. Why can’t I have a record that sounds like that?” I told him, “You just have to approach it from that period of recording, with two mics and a ‘less is more’ vibe, to keep things open-sounding.” So he was excited about that, but then he decided he wanted to go to Miami because there were too many distractions working so close to home, I think.

MH: The studio in Miami at Criteria was not the studio that all those great records had been made in. The Eric Clapton records and the Allman Brothers records that were made there were all in this little room, and now, it’s their tape closet. They’d built this studio and had this huge soundstage where they shot a lot of videos, but it was this big, white, plaster room. It had no vibe and no sound to it. I was trying my best, but it sounded terrible.

DL: I’m just so glad that we got out of the ’80s. I like records where the drums are back in the mix a little bit. A lot of great records from the early ’60s have that—huge James Brown records—where the drums are not hitting you in the face; it’s the bass that’s driving it. All great Motown records, with James Jamerson on bass, or old Dr. John records. It sounds as though there’s lots of people in the studio, with some people sounding further back, but that’s because they were in the back of the room! And so we were afforded that luxury on Time Out of Mind, because with a lot of people in the room, I could play with the sound and get the feel we wanted, and not feel like I had to make the drums loud to catch up to any kind of a trend.

DL: At the end of the Miami sessions there was a bit of a funny vibe. I thought “I Can’t Wait” was a single because we had a really badass demo of it from Oxnard. It was more hip-hop, so I thought, “OK, that’s the tip of the iceberg. I want to go the distance with that.” When we got to Criteria, it was one of the last songs we cut, but we never got the feel. And my heart sank. I kept pushing to go back to the feel of the demo, but by that point we’d been in there maybe a little too long. Bob ran out of patience, and that was the end of sessions. We left in a little bit of a rushed state, unfortunately. But it was because I really had a vision for “I Can’t Wait” that I don’t think we got to on the Time Out of Mind record proper. So if there’s any talk about disagreements, it would be all about “I Can’t Wait,” only because I wanted the best for Bob. I really wanted him to have a hit. I thought “I Can’t Wait” would be the song, but it wasn’t. I was hurt for a minute, but we got over it.

MH: At the end of the sessions, Dan didn’t even want to hear them. He thought we’d made a blues record [and] he didn’t want to do that. But I gave Bob a cassette with all the mixes. And that was that. After we left Miami, we didn’t hear from Bob. But like a month later, Bob calls me at home and says, “Mark, you think we got a record?” I said, “Yeah, yeah, I think you should come back in and we can fix a couple of things, but the record’s there.” But then I didn’t hear from him for another month. Then he calls me back. “Mark, I was just at my friend’s apartment in Santa Monica and I was playing him the tape you made me. And there was a knock on the door. It was his neighbor from down below, asking, ‘What are you guys listening to? I really gotta have it. It sounds incredible.’” So Bob tells me this whole story, and we agreed that he’d come back up to Oxnard and do some small vocal changes and just strip everything out of there that was messy and give it a rawer sound. So that’s how Time Out of Mind almost didn’t come out.

DL: There was a little bit of a hangover from Oh Mercy, when I thought [Bob] lost interest a little bit at one point, and I clarified that that was not about to happen. We had a moment and I said, “This is my life!” He said, “It’s my life too!” We were like a couple of teenagers arguing. And we just sat there and didn’t say anything else. Then he said, “All right, Dan. Let’s go.” And we didn’t talk about it again. I guess there was a little bit of friction existing from Oh Mercy that carried into Time Out of Mind, but it was nothing bad. Bob asked me to take the picture for the album cover. So we were in a good zone at that point. Besides, whatever disagreements we had along the way, that’s making a record. Bob was all in. There’s no doubt about that. And I love Bob for that. He’s the master, but he’s a worker. And I was very impressed with his attention to detail. Listen, man, we should all just be happy that there’s a masterpiece to be talking about.

MH: Once we got into mixing, we made it sound cool. Bob was really on top of things, especially the vocal sound. He always wanted to have that vocal amp in there to make him sound raspy and so it would sound like an older guy and a funky old record. That’s the Time Out of Mind sound, for sure.

DL: I think the [Grammys] did the right thing with naming that the Album of the Year. It was unlikely and unexpected and perhaps at a time where people were like, OK, here he comes again. But we delivered this thing that had emotional depth. It addressed certain issues that people don’t want to talk about. It had a lot in it that stopped people in their tracks. But I should make one comment here. Bob is obviously one of the great lyricists out of America, and how does one measure up to that? Now, this is my arrogant line: The way Danny Lanois measures up to that is by being as great as Bob at his thing and bringing that to the table. And if I do that, I’m ready for the arm wrestle.