The Beatles, not yet the Fab Four, released their second single, “Please Please Me,” in January 1963. That disc was a precursor of the British invasion of American musical culture. It was also part of a wave of radical cultural change in Britain that engulfed theater, movies, literature, and television.

It was like a dam had burst. A new generation swept away an old order that had resisted innovation since the end of World War II. Oddly, journalism was late to the party. Most national newspapers were owned by geriatric lords still blind to change, particularly the threat posed by television news.

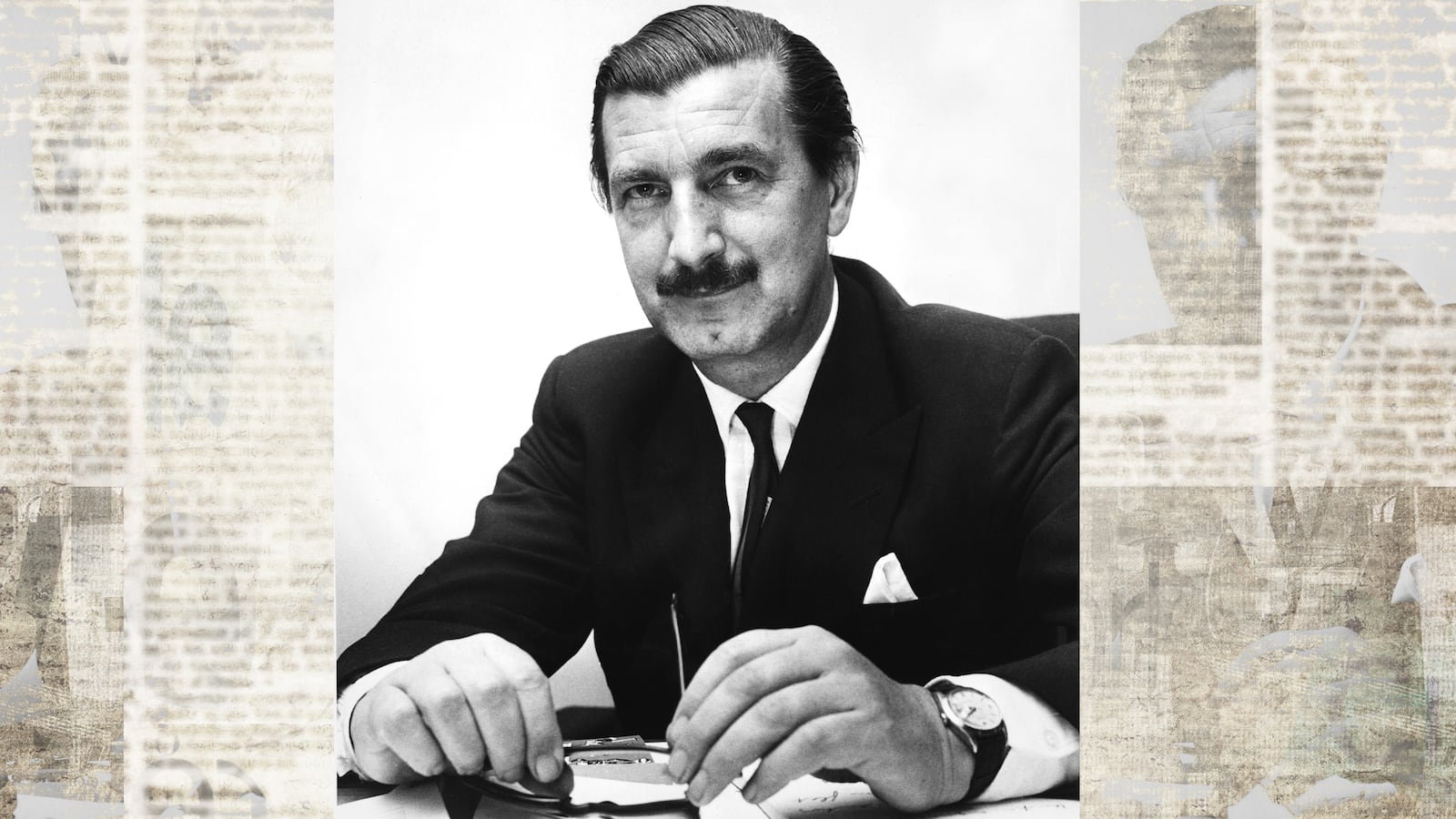

There was one exception to this complacency, and it could not have been embodied in a more unlikely figure. Outwardly, Denis Hamilton, the editor-in-chief of the Sunday Times, resembled his biography, a man with a distinguished war record as a lieutenant-colonel in the army and still, as a civilian, dressed correctly in the style of the stiff upper lip officer class.

In fact, Hamilton had risen from a working-class family, getting a job before the war as a reporter on a provincial daily. For him, and others, the war was a huge meritocratic change of fortune, releasing in him a talent for the leadership of men in battle and for spotting similar gifts in others drawn from a broad swath of backgrounds. Hamilton also possessed, in the Hemingway term, a finely tuned bullshit detector.

He was often hard to read. This façade had baffled the Canadian newspaper baron Roy Thomson, when he bought the Sunday Times in 1959, and inherited Hamilton with the paper. “He’s a fellow that doesn’t display himself” said Thomson. But, as Thomson poured money into building and promoting the paper, Hamilton flourished, launching two innovations from North America, a second section of the paper for arts and features, and a Sunday magazine. By 1963, Hamilton was ready for another big step, this time homegrown.

Almost to the day when that Beatles single began to appear in the charts, I arrived at the Sunday Times with two colleagues from a weekly newsmagazine, Topic, that had run out of money 10 weeks after I became its editor. We had been developing long-form investigative reporting of major events (one was the Cuban Missile Crisis that I covered from New York.) When the magazine folded, Hamilton called me and said, simply, “I like what you have been doing. Come here and do it for us and bring your two best people with you.” Within a few weeks, that call led to the creation of the Insight investigative team.

How all this played out is told in a new book, The Sunday Times Investigates, Reporting That Made History. The book reprints 12 of Insight’s major investigations, published over nearly 60 years. Looked at over that range of time, the story of Insight becomes a sobering commentary on how the conflict between journalism and countervailing powers, political, commercial, and legal, is always a test of how sound a democracy really is. It shows how frequently in Britain, like the U.S., the interests of the powerful override those of the powerless.

Until Insight appeared, no British broadsheet newspaper had ever practiced investigative journalism. Muckraking had been confined to the tabloids, and limited to soft targets, like brothel keepers and scandalous society divorces. Hamilton saw it as another step in giving the Sunday Times a journalistic edge. As it turned out, the authority of the paper opened doors that otherwise would have been slammed shut and gave us a string of highly placed sources. All this emerged as we covered our first major investigation, into one of the greatest scandals of the age, the Profumo Affair.

Three weapons of intimidation create a minefield in the path of British reporters: the Official Secrets Act; the particularly onerous and easily invoked libel laws; and the dangerously broad legal tripwire, contempt of court. Newspaper proprietors were traditionally leery of stories that risked invoking any of these. But it was the editors and reporters who were in the greatest danger. Only months before we arrived at the Sunday Times, two Fleet Street reporters were jailed for contempt of court when they refused to reveal sources for stories they wrote about a spy scandal involving the most serious breach of the Royal Navy’s secrets by a Russian mole since the end of the war.

Each of the Insight investigations in the book illustrates how a particular body of interests wants to cover something up—and, in some cases, prevails—at least for a while.

The basics of the Profumo Affair were that John Profumo, the Secretary of State for War (equivalent of the Defense Secretary) was sleeping with a showgirl, Christine Keeler who, at the same, was sleeping with a Russian intelligence officer, Eugene Ivanov.

That triangle, though reckless for Profumo, is too simple to explain the actual effects of the scandal. It introduced a cluster of interests that wanted the story shut down: Profumo himself, who assumed he was securely shielded by the libel laws; a prime minister and government that had been woefully negligent; the security services, who were equally embarrassed; bent cops who coerced witnesses to portray Keeler as a prostitute and her mentor and surrogate father, an osteopath named Stephen Ward, as a pimp; a justice system deployed to find a scapegoat, Ward, to draw attention away from a decadent ruling caste; the royal family because of Prince Philip’s friendship with Ward; and a long-running and unpoliced criminal racket that exploited immigrants.

British Secretary of State for War John Profumo, arrives at the House of Commons, London in 1962. In 1963 Profumo was forced to resign over his affair with Christine Keeler.

Ron Case/Keystone/Hulton Archive/Getty ImagesTo say that this was an education for Insight in navigating minefields is putting it mildly. Libel, the first impediment, was removed when Profumo, after months of lying, was forced to confess and resign. During that time, Insight had built a dossier that went deep into the political background. With the resignation, we ran the first full-length Insight narrative reconstruction headlined “The Three Stages of the Affair,” by far the longest piece ever to run in the news pages of the Sunday Times.

This was, however, just the overture to the opera. In further reporting we discovered a very useful method to interrogate our own work, later to become standard practice: who knew what, and when did they know it? This established one of the most politically damaging facts, that it had taken 123 days for a security services report on Profumo and Ivanov to reach the desk of Prime Minister Harold Macmillan. The cumulative effect of our reporting played a large part in Macmillan’s decision to resign later in the year. (Denis Hamilton was a long-time personal friend of Macmillan but never tried to influence our reporting.)

There were still things we didn’t print—or even suspect. The security services warned us off pursuing Prince Philip. We didn’t persist because we judged he was probably innocent and, in any case, he was marginal to the larger political story. What we didn’t know was that the spooks had something much bigger on their minds, a far more dangerous rot at the heart of their operations (see below). The worst outcome of the affair was a conspiracy that we never nailed at the time. The police and the judiciary so successfully framed Stephen Ward, on the bogus charge of pimping, that he committed suicide before he could be sentenced. And at least one other cabinet minister who had shared Keeler with Profumo escaped without detection. We did, however, have an enduring success in exposing the criminal racket, greatly helped by the fact that its instigator, a property magnate named Peter Rachman, was dead and could therefore not sue for libel. This part of the story was the first Insight reporting to lead to legislative reform, as well as giving the racket its name, Rachmanism.

Lost in the parliamentary hysteria of the Profumo debacle was a brief statement from the government that a foreign service officer, missing from his post in Beirut since early in the year, had defected to Moscow. His name was Kim Philby. It was not until 1967 that Insight was directed to take a closer look at Philby, and when they did they uncovered the most sustained and catastrophic act of treachery in the history of MI6, the agency supposed to detect and eliminate Soviet agents in the West. Philby had actually been in charge of the MI6 section hunting down agents while himself being Moscow’s highest-placed mole. How Insight exposed Philby is one of the new book’s most gripping narratives. It’s also a devastating indictment of the self-protecting culture that permitted such a failure and then resorted to extreme measures to try to stop the Insight revelations.

The editor who launched the Philby investigation was Harry Evans, who took over at the Sunday Times that year. (I left the paper in 1966 to work with David Frost on his first primetime television interviews.) Evans already had a track record leading investigations at the Northern Echo, a provincial daily he edited. Now, given the resources to build Insight into a larger team, he saw the Philby story as a way into what he described as “a closed world whose stock in trade is deceit.”

This meant that, as soon as MI6 got wind of the team of reporters interviewing anyone who knew anything about Philby, Evans was summoned by a senior Foreign Office official who was MI6’s point man. “You’ll do more damage with the Americans if you write about Philby,” he warned. That was the official line: that the Profumo case had already pissed off the FBI and the CIA with its old-boy network laxities and more of the same would do lasting harm. Moreover, they insisted, why bother with Philby? He was a boring minor player. But the Insight team had already linked Philby to a ring of spies recruited at Cambridge University in the 1930s. Philby was, by far, the most lethal of them—from early in the war he joined the security service and began feeding Moscow with top-quality intelligence, and, come the Cold War, his information had led to the deaths of hundreds of Western agents.

Hovering behind the official effort to shut down the investigation was the threat of the Official Secrets Act. There was now a Labour government in power. Although they had little sympathy for the dilatory toffs who were now in deep shit they were anxious not to look soft on Russia—a suspicion widely held in Washington. There was one step short of invoking the Act and they took it. Evans got a letter from a body called the D Notice Committee. It had no force in law. It was part of a mutual agreement between the media and government to alert editors to stories that might inadvertently jeopardize national security. The letter warned, “You are requested not to publish anything about identities, whereabouts, and tasks of persons of whatever status or rank who are or have been employed by either Service [MI5 or MI6].”

With the backing of Denis Hamilton, Evans ignored the letter. (The whole story had featured the kind of over-promoted mediocrities that Hamilton had encountered in the wartime army and that he despised.) The Philby investigation was published over three issues during October 1967. It was a tour de force in narrative journalism, relentless in exposing what had been until then buried in that “closed world.”

The final part of the reporting opens with a lede crafted in a style that Insight made its own, known as the “delayed drop” in which an atmosphere is established with a hint of the ominous: “At 9.30 a.m. on his last day in England, May 25, 1951, Donald Maclean was walking decorously from Charing Cross Station to his room in the Foreign Office. Guy Burgess, never a devotee of early rising, had only just got out of bed in his New Bond Street flat by Asprey’s. He was reading The Times and drinking tea made by his friend Jack Hewit. Everything was relaxed and unhurried.”

The “last day” reference presages that Burgess and Maclean, two other Soviet moles, are about to defect to Moscow. In the end, no move was made by the government to use the Official Secrets Act to shut down publication, although apparently there was a hard core in the security services who pressed for it. It was a milestone for Insight and a foundational achievement for Evans as an editor.

Seven years later, John Le Carré published Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy, the bedrock of his canon of literary thrillers that hinges on a mole similar to Philby. But what Le Carré left out, and what makes reading the Insight account again so much more chilling than fiction, is the picture it gives of the pervasive institutional decay of the British security services—the arrogant incompetence—which, but for this reporting, might never have been admitted.

Evans’s next confrontation with a government had a very different outcome. It caused a schism in the team and was a painful example of how the fog of war can trap an editor in conflicting loyalties, and it left some lasting scars among the reporters.

One of those reporters had shown extraordinary tradecraft on the Philby story. Murray Sayle, like a number of Insight’s stars, began in the paper’s newsroom as a one-day hire for the Saturday shift. He was a rangy young Australian with a rolling stone experience, including a stint covering the Vietnam war. Evans had sent him to Moscow to track down Philby. Knowing Philby was an addicted cricket fan, Sayle figured that in order to follow the game Philby would depend on reports in The Times and that British expats had the paper mailed to the central post office in Moscow. Sayle surveilled the post office for several days and, one morning, recognized Philby leaving with the paper under his arm. Using a well-practiced charm, he persuaded Philby to give him an interview—in fact, several interviews—landing a big scoop for Insight.

Demonstrators run from tear gas during the Bloody Sunday riots, which broke out after British troops shot civilians during a civil rights march in Derry, Northern Ireland, January 30,1972.

PL Gould/Images/Getty ImagesOn Sunday, Jan. 30, 1972, the infamous Bloody Sunday when 13 Catholic civilians taking part in a protest against British rule in Northern Ireland were shot dead in Londonderry, the paper’s resident expert on Ireland happened to be uncontactable in Africa. Sayle was assigned instead to head the Insight coverage. By Sunday evening he was in Londonderry, joined by the paper’s Belfast correspondent, Derek Humphry.

They had five days in which to reconstruct the events for the paper’s next issue. As scores of reporters and photographers from all over the world descended on Londonderry, Sayle made his focus the forensic core of the story: establishing exactly who the victims were and how they died. Using his Vietnam experience, he fixed the places in the street where they fell, established where the British Army shooters were placed and plotted the trajectory of their fire. It was clear that the civilians were unarmed and innocent victims and not, as the Army claimed, linked to the Irish Republican Army.

Sayle drew a map to support his reporting and, on the Friday, sat down with Humphry and combined their work in one narrative that he then filed to London.

Late that night they were told that the story would not run. Two Insight editors had decided that there were “internal contradictions” in the reporting and more time was needed to interrogate the details.

Sayle remained in Northern Ireland and Humphry returned to London, expecting to resolve the issues and get their story into print the following Sunday.

But then all reporting was halted by government diktat. They announced that a tribunal of inquiry under Lord Chief Justice John Widgery would investigate and report. This device, an official tribunal, created in 1921, was a very efficient way of gagging all the media: to publish anything until the tribunal reported would bring a charge of contempt of court.

Humphry felt that a moment had been missed when his and Sayle’s reporting could have pre-empted an official cover-up. Now 91 years old and living in Oregon, he told me recently: “Harry asked me to go back to Derry with the Insight team but I declined. I told him I was so upset at British soldiers shooting British citizens, some up the arse with a second bullet, that I would not join the team.” (Later, Humphry won the Martin Luther King Memorial Prize for Because They’re Black, a pioneering book about the Black experience in Britain.)

In the interregnum, Sayle sent a long memo to Evans explaining his method. He had studied more than 200 eyewitness accounts. He concluded that the military operation had met none of the rules set down for an engagement using deadly weapons and was, therefore, illegal. In the event, neither Sayle’s reporting nor his map were ever published.

When Sayle sought to retrieve his original copy in the office it had disappeared from the Insight files. Nobody could explain why. In 1998, when Sayle was based in Tokyo, his fax machine suddenly started up and out came a verbatim version of it—though not as he had typed it. It had been found among the records of the National Council for Civil Liberties. Sayle could not discover how it got there.

This traumatic episode does not appear in the new book. All it prints is the Insight account published on April 23, 1972, after the tribunal’s report, widely regarded as a whitewash, was published by the government. Insight independently interviewed 250 witnesses, including members of the IRA. The reporting dissects the official account but the closest it gets to challenging it was to say that Widgery had made an omission in his verdict “which shakes confidence in the firmness of Widgery’s conclusion that soldiers were fired on first.”

Sayle said later, “The article I wrote diverged from the official line. Harry did not endorse our conclusion that not a single shot had been fired by the IRA at the heavily armed paratroopers.” Sayle went on to work for the paper, but no longer with Insight. In 1998, as part of the effort to end violence in Northern Ireland, Prime Minister Tony Blair set up a new tribunal to probe the shootings. Sayle and Humphry were called as witnesses. The findings, released in 2010, vindicated their reporting and Sayle’s map that accurately choreographed the slaughter. The British government made an unprecedented apology to the families of the victims.

There is a timely lesson here about the value of journalism and what it can capture in the real live moments of an event that is otherwise irretrievable. The Jan. 6 insurrection has shown that the rewriting of history begins very early. At the Capitol there was, luckily, a stubborn and irrefutable visual record of by-the-second truths. Sayle and Humphry accurately captured similar details of the moment before they could be contaminated. The army swiftly moved to change the narrative to cover their role. The work of two reporters had caught and preserved the truth, but was ignored.

For sure, the pressure on all the British papers to toe the official line had been relentless, and many were ready to do so. There was a great reluctance to accept that such a savage act had been carried out by the army. Many years later, Evans told Sayle that he had not read his report when the decision to kill it was made—he deferred to Insight’s editors. He didn’t accept Sayle’s belief that publication “could have saved much subsequent bloodshed.” There is no doubt, though, this was not Insight’s most glorious hour—or that Evans, whether he admitted it or not, was more than ever aware that, in his own words, “news is often something that somebody somewhere doesn’t want you to print.”

The greatest test of that belief would prove to be, for Evans and for Insight, a story that caught his attention while he was still editing the Northern Echo, when he learned about hundreds of children born in Britain who had been born with foreshortened limbs, or no limbs at all. Their mothers had all taken the drug thalidomide, to treat morning sickness and other stresses of pregnancy. In 1967, after discovering that none of the families had received any compensation, Evans launched an Insight investigation into the origins of the drug. By then it was clear that as many as 20,000 babies, worldwide, had been born deformed as a result of the drug’s effects.

Immediately, word of the investigation engaged the lawyers of the British marketers of the drug, Distillers Biochemicals, and its German creators, Chemie Grunenthal. They were abetted by a Tory government health minister, Enoch Powell, who showed no sympathy at all for the victims.

Young victims of thalidomide born with malformations at Chailey Heritage House in London, England on October 12, 1962.

Keystone-France/Gamma-Rapho via Getty ImagesThe resulting contest between them and the paper lasted years. The first Insight investigation, published in May 1968, traced the drug’s evolution to a chemist who during World War II had used prisoners at the Buchenwald concentration camp as guinea pigs to try out a serum. (Evans later named thalidomide as “the last Nazi war crime.”) The final investigation appeared in June 1976, after months of being suppressed by British courts using the threat of contempt of court.

To end this deadlock, Evans appealed to the European Court of Human Rights. By a vote of 13-11 they ruled that by deploying the catch-all contempt of court gag the British lawyers had breached Europe’s standard of free speech. Over and above the actual details of the case what stands out in retrospect is how lonely a crusade this was for Evans and the Insight team. The rest of the British media, including the BBC, were gamed by the drug company’s flacks and cowed by threats of legal action. One editor, asked by Harry why his paper wasn’t equally exercised by the scandal, joked, “We’re saving the space to cover your trial.”

As the investigation stretched out over years, the team grew to a total of 17. And the work brought a significant change to the Insight culture, by introducing two outstanding women. Until then, Insight had always been dominated by men. They combined three recognizable types: a permanent core of editor-writers, including some notable polymaths; itinerant reporters seasoned with world experience, like Sayle; ad hoc additions with specialist knowledge when needed.

Elaine Potter and Marjorie Wallace fitted none of these slots, but each became indispensable in the investigation’s greatest achievement, getting fitting financial compensation for the British families. (In Germany, where five times as many families were affected, a meager compensation had been settled in 1969, long before the companies’ full culpability was exposed.)

In London, successive public defenders appointed to negotiate for the families had been outgunned by a phalanx of highly paid corporate lawyers. Elaine Potter, an Oxford graduate with a PhD, was working as a freelance in the features department when she was drafted to Insight. She had no gumshoe reporting experience, but her intellect cut through the legal crossfire so effectively that she helped guide the legal theory that finally got the Distillers company to accept a liability of 28.4 million pounds, an enormous sum at the time. Marjorie Wallace had started out in the 1960s as a whip-smart researcher on the David Frost program, which is where I first met her. She arrived in the Sunday Times newsroom as the thalidomide story began to unspool. She told me recently that she found Insight’s aura of intramural masculine competitiveness intimidating, and she was no shrinking violet herself. She had a natural empathy that made itself apparent to the children’s families and, patiently, she was able to persuade them that the Insight investigation would end up getting them the settlement they deserved.

Both women went on to have consequential careers. Wallace wrote a book, On Giant’s Shoulders, about one of the thalidomide families. She later founded a charity focused on mental health, an issue on which she has since become an influential activist, and wrote a book, Silent Twins, about two Black girls in Wales who, because of psychological pressures, communicated only with themselves. The book inspired two movies, several plays and two operas. Potter continued at Insight, co-authoring two books based on team investigations, Suffer the Children, about thalidomide, and Destination Disaster, about the causes of a plane crash. Later, she founded the Bureau of Investigative Journalism in London.

With the thalidomide investigation, Evans had crossed the line from investigative reporting to a crusade, openly advocating for the redress of a wrong by people who had been protected by governments and a legal system that put corporate interests above public interests. In his memoir, Evans wrote, “The much-feared law of contempt was going to sanctify a gross injustice. It was urgent to shout that it must not be allowed to happen. Was I emotional about the thalidomide families? Yes, I was, but my decision to launch a campaign was not a sudden impulse… the paper had to be ready to commit the resources for a sustained effort, and it had to open its columns to counterarguments and corrections of fact. No campaign should be ended until it had succeeded—or was proved wrong.”

Evans’ courage and commitment to Insight’s journalism established him as one of Britain’s most acclaimed editors. In 1981, when Rupert Murdoch took over the Sunday Times and the daily The Times, he moved Evans to the daily, but his editorship ended after a year. The new proprietor was not a hands-off boss like the Thomson family, and a campaigning editor was too much like a rival in authority; Evans was forced out. His fall was partly due to the end of his long and sustaining partnership with Denis Hamilton. With the takeover, Hamilton became chairman of the two papers, but this removed him from editorial power. In his memoir he writes that Murdoch was “a poor picker of men. He had no judgement of what makes a good editor, only gossip about who was good or bad.” Hamilton left the company at the end of 1981, to concentrate on a job he already had, chairman of the Reuters news agency. A man who instinctively disliked the limelight had fathered a golden age of journalism at the Sunday Times, but the days when nearly a score of reporters could be assigned to an investigation that lasted years were clearly over.

Nonetheless, Insight has survived. The Sunday Times and The Times, like the Wall Street Journal, have adapted to the digital age and, for the moment, their journalism seems safely walled from the stink of Fox News. The book ends with a blockbuster investigation by the current Insight team, led by Jonathan Calvert and George Arbuthnott: a surgical indictment of the Boris Johnson government’s handling of the pandemic that, like earlier Insight classics, has become a bestselling book, Failures of State.

Nearly 60 years after I launched Insight, Calvert called me to go over the origin story, which opens the book. Talking across the generations was remarkably easy. We shared similar experiences. There was also an odd symmetry: In 1963, Insight began with a story, Profumo, that also savaged a Tory government. The inescapable difference was that, back then, any prime minister as mendacious and incompetent as Johnson would have been defenestrated by his party, not indulged. Another difference is that, instead of a one-man press office, 10 Downing Street now attempts to limit the damage to Johnson with an expensive spin machine. Responding to the Insight revelations, it issued a 2,000-word blog post so full of errors and misinformation that it simply compounded the picture of a clueless government.

Calvert told me that under Emma Tucker, the paper’s current editor, the team is given the same kind of independence and time to go deep that I asked for, and got. Moreover, the paper has discovered that long-form narrative journalism is a big draw for its digital edition: Failures of State drew the largest ever readership for the website.