On an evening two years ago, Rep. Chuck Fleischmann (R-TN) walked out of a closed-door dinner on Capitol Hill without a campaign check or valuable contact, but something else: sobering new knowledge about nuclear weapons.

In a recent interview, the congressman recalled the dinner, where he sat alongside Democratic and Republican lawmakers, listening to top experts explain the finer points of nuclear weapons policy and urge them to pay close attention to an issue that has fallen on Congress’ backburner.

Everything was off the record—what the guests said, what they were asked, who they were, where the dinner even was.

“The level of threat is constant,” said Fleischmann. “The margin for error is zero. Think about the worst-case scenario.”

Washington is home to countless private soirees and high powered dinner clubs, but there’s only one gathering devoted to nukes. They take place once every couple of months at a restaurant or townhome on Capitol Hill and are organized by former Democratic congressman John Tierney, who heads a group that advocates nuclear nonproliferation. Attendance is usually strong—at least a couple of dozen lawmakers show up—and they’re joined by experts like former Secretary of State John Kerry and former Energy Secretary Ernest Moniz.

Though some regular attendees of the dinners dutifully keep the shroud of secrecy around the dinners in place, sensitive information is rarely spilled at these get-togethers. The confidentiality is important for another reason: so lawmakers can ask dumb questions, get into heated arguments, and actually learn—far away from the cameras of a congressional hearing and without fear of blowback or ridicule.

With global nuclear threats on the rise, and with Congress’ general knowledge of those threats on the decline since the end of the Cold War, those involved with the dinner say it’s more important than ever for lawmakers to have an informal venue where they can bolster their nuclear bona fides.

But the grave nature of the issue at hand—nothing short of preventing the detonation of weapons that could end human civilization—imbues everything with a feeling of existential importance. “As I say to members, if you make a mistake on a financial bill, someone’s going to lose a few bucks,” Tierney told The Daily Beast in an interview at the offices of the Center for Arms Control and Non-Proliferation, his advocacy group. “If you make a mistake on one of these bills... catastrophe.”

Within the world of nuclear nonproliferation, there is not an especially high level of confidence in Congress’ capacity to develop smart policy that would prevent such a catastrophe. At a recent hearing of the House Armed Services Committee, which oversees nuclear weapons policy, lawmakers asked basic questions that revealed their ill-preparedness on the issue, wrote Hans Kristensen, a nuclear security expert at the Federation of American Scientists.

The hearing, he wrote, “descended into partisan posturing, cheerleading of panelist responses, and surprisingly uninformed questions that demonstrated a worrisome lack of basic knowledge about nuclear forces. Not good for a committee that is supposed to oversee billions of dollars of nuclear weapons programs.”

Indeed, though the decision to deploy a nuclear weapon rests with the president and not with Congress, lawmakers hold the power of the purse, setting funding priorities for the military’s nuclear arm and shaping the arsenal the president has on hand if a nightmare scenario were to arise. Since Donald Trump took over as commander-in-chief, however, some Democratic lawmakers have introduced legislation to block the president from launching a first nuclear strike without securing approval from Congress.

That effort is reflective of deep distrust of Trump, and an anxiety that his twitchy fingers could just as soon fire off a nuclear weapon as an errant tweet. But it’s also reflective of a global landscape with an increasingly uneasy nuclear balance. In the last two years, North Korean dictator Kim Jong Un has steadily worked to cement his country as a nuclear power despite Trump’s charm offensive to persuade him otherwise. Kim has conducted two separate missile tests since April.

Elsewhere, Iran announced on May 8 it would no longer comply with the nuclear deal it signed in 2015 with five European countries, one full year after the U.S. pulled out of the agreement. Two nuclear-armed neighbors, India and Pakistan, flirted with war earlier this year. And Washington’s relations are spiraling with two powerful nuclear-armed rivals: China, which is racing to match America’s military capability, and Russia, which still has as many nuclear warheads as the U.S.

But on Capitol Hill, some experts still see a lingering post-Cold War nuclear triumphalism on display among lawmakers.

“After the end of the Cold War, a lot of people assumed that the threat went away,” said Joan Rohlfing, president of the Nuclear Threat Initiative, a nonproliferation advocacy group. “Unfortunately, the dangers have increased as these new pathways to nuclear use have come up on the scene, and the old threat still hasn’t gone away. It’s an even more dangerous world today, and it’s one that’s largely been unmanaged.”

“It’s really important for members across the board, both sides of aisle, to put their nose to the grindstone and invest in learning about this issue that is an existential national security threat,” said Rohlfing, who was a witness at this year’s Armed Services panel hearing on nuclear policy.

That’s where the dinners are designed to help. Several members of Congress from both sides of the aisle confirmed to The Daily Beast that they participate in the series and touted it as an essential resource for lawmakers.

Fleischmann, the Tennessee Republican, was initially interested in the dinner group because his district is home to the historic Oak Ridge nuclear laboratory. Though he left his first dinner sufficiently concerned about nuclear threats, he did also come away with a bit of hope that Congress could cast aside politics in order to deal with it.

“It’s a mix of Republicans and Democrats,” Fleischmann told The Daily Beast, recalling that he was seated alongside the likes of Sen. Bob Casey (D-PA) and Sen. Rand Paul (R-KY). Tierney, the group’s organizer, would not say specifically which members attend.

Fleischmann could not divulge exactly what was said at the dinner, but he characterized the mood as collaborative and nonpartisan. “Ideology was thrown to the wayside,” he said. “The focus is on, how do we disincentivize people or nations from going down that path?”

Sometimes lawmakers come to dinner with very basic questions about nuclear policy—what’s the nuclear triad, anyway?—that would promptly spark mockery if posed in a public setting.

That’s why the privacy is so important, said Tierney. “If you ask some of these questions at a committee hearing, you’re going to get killed,” he said. “It’s an expectation that isn’t realistic, but the public doesn’t know that.”

The setting also frees up lawmakers to push harder on controversial topics, like cost, without fear that any devil’s advocating might be used against them later.

“Whatever is said in the room stays in the room,” Tierney said. “We don’t disclose the people who participate, all in the idea they want to be comfortable, they want to ask whatever questions they want to ask, explore any thought process they want to explore, without it being brought back on them.”

Rep. John Garamendi, a California Democrat, said open hearings are a necessary part of the process but that these private meetings are just as important. Demonstrating that “private” remains the operative word there, Garamendi told The Daily Beast about the benefits of the nuclear dinner series without definitively saying he attends it or that it even exists.

“In a nonclassified setting, it is frankly the best way for us to gather detailed information and have a frank discussion,” said Garamendi. “Generally we learn more than we would at a public hearing with the normal rotation of five-minute questions, which are five-minute speeches.”

In addition to people like Moniz and Kerry—both leaders in the Iran nuclear deal negotiations under Barack Obama—guest speakers have included Thomas Pickering, ambassador to the United Nations under George H.W. Bush; and James Cartwright, a retired Marine Corps general who has advocated for the U.S. and Russia to cut their nuclear warhead stockpiles by 80 percent.

The dinner series has been going strong for several years—over 100 lawmakers have attended at least one session, Tierney says—and his group hopes to expand that number and keep the program fresh as members cycle in and out of Congress.

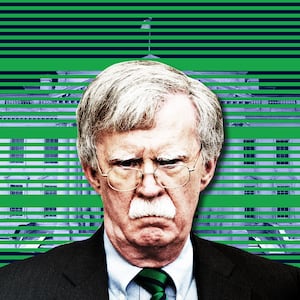

Among some newer members, he says, there exists somewhat cavalier and troubling attitude toward nuclear nonproliferation, echoing the president’s national security adviser, John Bolton, who has a long history of contempt for arms control agreements.

“You get a sense that some people have probably lost a little bit of appreciation for what the consequences of a nuclear explosion are,” said Tierney. “It’s another area we could really do better.”

After all, there are few issues of truly existential weight on Congress’ docket. Shouldn’t they have to learn about one?

“Look, if we’re talking about an existential threat to the nation, they have to care about it,” said Rohlfing, the nonproliferation advocate.

“Nuclear issues aren’t only an existential threat, but that’s a really small and finite list, and you would hope that members would at least feel obliged to learn about and serve their constituents’ interests where existential threats are concerned.”