It is, quite frankly, incredible how the Dylan Farrow-Woody Allen saga has played out in the public discourse. But, for all the fiery op-eds by journalists on the child sexual abuse allegations levied by Farrow against Allen, and the subsequent firestorm of controversy, few have sat down and analyzed the 33-page decision from New York Supreme Court Justice Elliott Wilk in Woody Allen’s 1992 custody suit against his former partner, Mia Farrow (Farrow would later go on to name one of her adopted children, Thaddeus Wilk Farrow, after the judge).

The decision, dated June 7, 1993, begins: “On August 13, 1992, seven days after he learned that his seven-year-old daughter Dylan had accused him of sexual abuse, Woody Allen began this action against Mia Farrow to obtain custody of Dylan, their five-year-old son Satchel, and their fifteen-year-old son Moses… what follows are my findings of fact. Where statements or observations are attributable to witnesses, they are adopted by me as findings of fact.”

But first, some background. The allegations of child sexual abuse committed by Allen against his adopted daughter, Dylan, first exploded in the media with writer Maureen Orth’s lengthy feature “Mia’s Story,” that was published in the Nov. 1992 issue of Vanity Fair magazine. Allen denied and continues to deny the allegations. No charges were ultimately brought against Allen, and the controversy lay dormant for years. Then, on Jan. 12, 2014, Allen was the recipient of the Cecil B. DeMille lifetime achievement award at the Golden Globes for his body of film work. A highlight reel played, and Diane Keaton accepted the award on Allen’s behalf. She even sang. Allen’s estranged son, 26-year-old Ronan Farrow—who’s about to launch his own show for MSNBC, and whom Mia claimed might be the offspring of Frank Sinatra—tweeted the following:

Followed by this tweet from Mia the morning after the Globes:

The Farrow tweets reignited the controversy, and on Jan. 27, Allen documentarian Robert Weide wrote a lengthy piece for The Daily Beast analyzing the claims that Allen abused a young Dylan Farrow. The piece was read by millions, and further stoked the flames. Then, on Feb. 1, Dylan Farrow published an open letter on Nicholas Kristof’s On the Ground blog on The New York Times’ website explaining, in vivid, heartbreaking detail, what Dylan says was a cycle of sexual abuse she allegedly suffered at the hands of Allen. The 78-year-old filmmaker responded with his own op-ed in the Times on Feb. 7, defending himself against the allegations and claiming that, as an impressionable child, Dylan had been manipulated into believing she was abused by his scornful ex, Mia Farrow, who still harbored resentment against Allen for having a sexual relationship with her adopted daughter, Soon-Yi Previn, whom Allen has since been married to for 17 years. Dylan then published a rebuttal in The Hollywood Reporter, addressing Allen’s op-ed point-by-point, and citing the ruling of Justice Wilk of the New York Supreme Court in Allen’s 1992 custody suit against Mia Farrow as support for her allegations against him. The custody suit was not an investigation into whether Allen abused Dylan or a criminal procedure, nor was Justice Wilk’s decision a binding legal conclusion regarding Allen’s guilt or innocence, but the judge did discuss the allegations in his decision in the case.

In his Times op-ed, Allen called Justice Wilk’s decision “very irresponsible” and that he “never approved of my relationship with Soon-Yi.”

Now, to New York Supreme Court Justice Wilk’s decision. Here are the biggest reveals in the court documents, in chronological order.

1. Allen’s Relationship with Mia

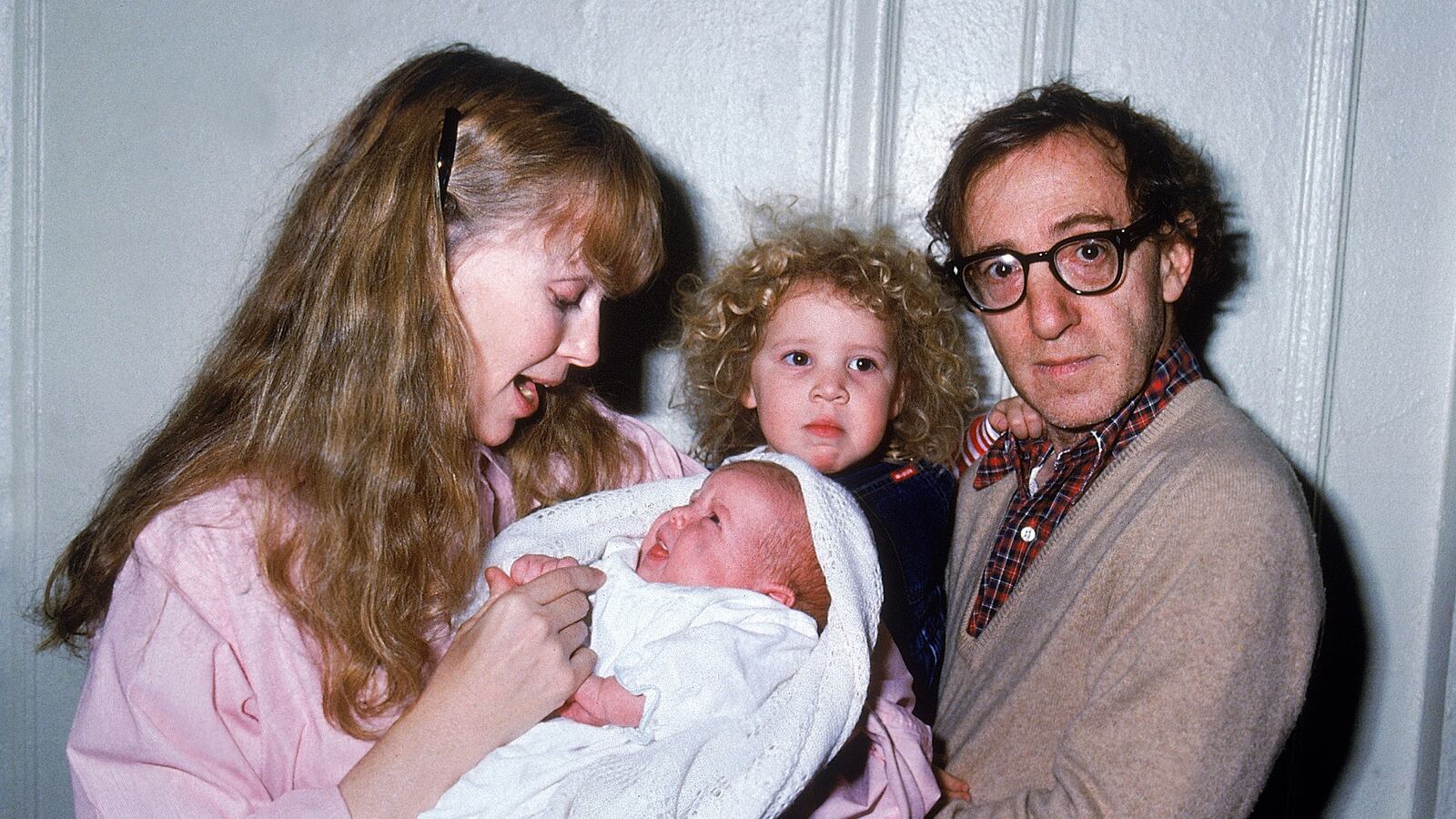

The decision says that, up until 1985, Allen had “virtually a single person’s relationship” with Farrow and “viewed her children as an encumbrance,” having “no interest” in them. Allen lived in his apartment on the east side of Manhattan, while Farrow lived on the west side with her kids. In 1984, Farrow told Allen she wanted to have his child. He was reluctant, and only agreed after “Ms. Farrow promised that the child would live with her and that Mr. Allen need not be involved with the child’s care or upbringing.” After six months of trying, Farrow chose to adopt a child and, since Allen “chose not to participate in the adoption,” she was the sole adoptive parent. On July 11, 1985, Dylan joined the Farrow clan.

2. Allen Warms to Dylan

The decision says that, a few months after the adoption, “Mr. Allen’s attitude toward Dylan changed.” He became more of a family man, spending mornings and evenings at Farrow’s apartment “in order to be with Dylan,” visited Farrow’s country house in Connecticut, and accompanied the Farrow-Previn family on trips to Europe in ’87-’89. He “remained aloof” from Farrow’s other kids with the exception of Moses.

3. Mia’s Relationship with Woody

The decision claims Allen showed “no interest in [Farrow’s] pregnancy” with their biological child, Satchel (now Ronan), and he did not “touch her stomach, listen to the fetus, or try to feel it kick.” And, a few months into the pregnancy, Farrow “began to withdraw from Mr. Allen,” and following the birth of Satchel, “grew more distant from Mr. Allen.”

4. Mia’s Suspicion Arises

According to Justice Wilk, Farrow became “concerned with Mr. Allen’s behavior towards Dylan” around 1987-1988. “During a trip to Paris, when Dylan was between two and three years old, Ms. Farrow told Mr. Allen that ‘[y]ou look at her [Dylan] in a sexual way,’” according to the decision. “You fondled her. It’s not natural. You’re all over her. You don’t give her any breathing room. You look at her when she’s naked.” She was suspicious of Allen because he’d read to Dylan in bed while in his underwear and permitted “[Dylan] to suck on his thumb.” Mia Farrow, her longtime friend Casey Pascal, Sophie Raven (Dylan’s French tutor), and Dr. Susan Coates, a clinical psychologist who treated Satchel, all testified that Allen “focused on Dylan to the exclusion of her siblings.” In the fall of 1990, when Farrow asked Dr. Coates to evaluate Dylan to see if she needed therapy, Farrow “expressed her concern” that “Allen’s behavior with Dylan was not appropriate.” Dr. Coates observed, “I did not see it as sexual, but I saw it as inappropriately intense because it excluded everybody else.”

5. Allen Adopts Dylan and Moses

In 1991, Farrow wanted to adopt another child, so, according to the decision, Allen said he would not take “a lousy attitude towards it” if Farrow would sponsor his adoption of Dylan and Moses. Farrow said that she agreed after Allen assured her he “would not take Dylan over for sleepovers… unless I was there,” and that he would “never seek custody” if their relationship dissolved. He adopted Dylan and Moses in December 1991.

6. Allen and Soon-Yi

Until 1990, Allen had “little to no contact with any of the Previn children” and had “the least to do with Soon-Yi,” of whom he said, “She was someone who didn’t like me.” In 1990, Soon-Yi asked Allen if she could go to a New York Knicks basketball game (he was a season ticketholder), and he agreed. They started going to more games, and by 1991, were discussing “her interests in modeling, art, and psychology.” On Jan. 13, 1992, according to the decision, Farrow found six nude photographs of Soon-Yi in Allen’s apartment that had been left on the mantelpiece, including one of her “reclining on a couch with her legs spread apart.” Farrow confronted Soon-Yi with the photos, but later said she “did not blame her.” Shortly after that, when Soon-Yi came clean about her “sexual relationship with Mr. Allen,” Farrow “hit her on the side of the face and on the shoulders,” and “told her other children what she had learned.”

7. Farrow’s Anger at Allen

Both sides retained counsel shortly after the Soon-Yi reveal, and in February 1992, Farrow gifted Allen with “a family picture Valentine with skewers through the hearts of the children and a knife through the heart of Ms. Farrow.” She also “defaced and destroyed several photographs of Mr. Allen and Soon-Yi.” In July 1992, Farrow had a birthday party for Dylan at her home in Connecticut and, after Allen “monopolized Dylan’s time and attention,” and Allen retired to a guest room for the night, Farrow “affixed to his bathroom door a note which called Mr. Allen a child molester. The reference was to his affair with Soon-Yi.” Justice Wilk’s decision goes on to say to that in the summer of 1992, Soon-Yi was fired as a camp counselor for spending all her time talking on the phone with a “Mr. Simon,” who was Woody Allen.

8. Aug. 4, 1992

On this date, Allen traveled to Farrow’s country home in Connecticut to spend time with the children. At the home was Allen; Casey Pascal (Farrow’s friend) and her three children; the Pascal nanny, Alison Stickland; Kristie Groteke, a babysitter employed by Farrow; Sophie Berge, the Farrow kids’ French tutor; Dylan and Satchel. Farrow had “previously instructed Ms. Groteke that Mr. Allen was not to be left alone with Dylan,” but for about 15-20 minutes in the afternoon, Groteke “was unable to locate Mr. Allen or Dylan. After looking for them in the house, she assumed that they were outside with the others.” But Allen and Dylan were not outside with them, according to Berge and Stickland. At a different point in the day, Stickland says she “observed Mr. Allen kneeling with his head on her lap, facing her body. Dylan was sitting on the couch staring vacantly in the direction of a television set.” When Farrow returned home, Berge noticed Dylan “was not wearing anything under her sundress” so Farrow had Groteke put underpants on Dylan. That evening, Stickland claims she told Pascal that she “had seen something at Mia’s that day that was bothering me,” and told of the TV room observation. The next day, Pascal phoned Farrow and told her of Stickland’s statements.

9. Dylan’s Recollections

After the Pascal call, Farrow asked Dylan “whether it was true that daddy had his face in her lap yesterday,” and this is Farrow’s testimony: “Dylan said yes. And then she said that she didn’t like it one bit, no, he was breathing into her, into her legs, she said. And that he was holding her around the waist and I said, why didn’t you get up and she said that she tried to but that he put his hands underneath her and touched her. And she showed me where… her behind.” Farrow then videotaped Dylan’s statements “over the next twenty-four hours,” and “Dylan told Farrow that she had been with Mr. Allen in the attic and that he had touched her privates with his finger.” Farrow phoned her attorney, who advised her to bring Dylan to their local pediatrician, which she did. Dylan “did not repeat the accusation of sexual abuse during this visit” and on the trip home told her mother she “did not like talking about her privates.” On Aug. 6, when she returned to the pediatrician—on the pediatrician’s advice—Dylan repeated what she told her mother on Aug. 5. Meanwhile a “medical examination conducted on Aug. 9 showed no physical evidence of sexual abuse.”

10. Mia’s Skepticism with the Doctors

Dr. Susan Coates, a clinical psychologist who treated Satchel, and Dr. Nancy Schultz, a clinical psychologist who treated Dylan, were two witnesses during the trial, which began on March 19, 1993. According to the decision, in the wake of the allegations, on Aug. 17, 18, and 21, Dr. Schultz would be chauffeured in Allen’s limo to the Farrow home in Connecticut to see Dylan, but Dylan “became increasingly resistant to Dr. Schultz,” and during the third session, “Dylan and Satchel put glue in Dr. Schultz’s hair, cut her dress, and told her to go away.” On Aug. 24 and 27, Farrow expressed anxiety to Dr. Schultz that she was seeing Allen in conjunction with Dylan, since Allen had filed suit for custody of Dylan. “Soon after that… I learned that Dr. Schultz had told [New York] child welfare that Dylan had not reported anything to her. And then a week later, either her lawyer or Dr. Schultz called [New York] child welfare and said she just remembered that Dylan had told her that Mr. Allen had put a finger in her vagina. When I heard that I certainly didn’t trust Dr. Schultz.” Farrow ultimately discontinued Dylan and Satchel’s therapy with Dr. Schultz and Dr. Coates, both of whom were treating Farrow’s children in conjunction with Allen. According to the decision, “Both Dr. Coates and Dr. Schultz expressed their opinions that Mr. Allen did not sexually abuse Dylan.”

11. More Testimony from Dylan

On Dec. 30, 1992, the Connecticut State Police interviewed Dylan. Dylan told them that “at a time Ms. Farrow calculates to be the fall of 1991” she witnessed Allen and Soon-Yi having sex at Allen’s apartment. “Her reporting was childlike but graphic,” says the documents. “She also told the state police that Allen had pushed her face into a plate of hot spaghetti and had threatened to do it again.” Then, says the decision, 10 days before a team from the Child Sexual Abuse Clinic of Yale-New Haven concluded its investigation, Dylan told Farrow for the first time that, in Connecticut, “while she was climbing up the ladder to a bunk bed, Mr. Allen put his hands under her shorts and touched her.” Farrow testified that as Dylan was saying this “she was illustrating graphically where in the genital area.” The Yale-New Haven team later “issued a report which concluded that Mr. Allen had not sexually abused Dylan.”

12. Conclusions on Allen

Regarding Allen’s response to his counsel’s question regarding why he sought custody of his children, the decision reads: “The most relevant portions of the response—that he is a good father and that Ms. Farrow has intentionally turned the children against him—I do not credit.” Furthermore, the judge concluded that Allen’s “trial strategy has been to separate his children from their brothers and sisters; to turn the children against their mother; to divide adopted children from biological children; to incite the family against their household help; and to set household employees against each other. His self-absorption, his lack of judgment and his commitment to the continuation of his divisive assault, thereby impeding the healing of the injuries he has already caused, warrant a careful monitoring of his future contact with the children.”

13. Conclusions on Mia

The decision reads: “There is no credible evidence to support Mr. Allen’s contention that Ms. Farrow coached Dylan or that Ms. Farrow acted upon a desire for revenge against him for seducing Soon-Yi. Mr. Allen’s resort to the stereotypical ‘woman scorned’ defense is an injudicious attempt to divert attention from his failure to act as a responsible parent and adult.” Furthermore, it states: “In a society where children are too often betrayed by adults who ignore or disbelieve their complaints of abuse, Ms. Farrow’s determination to protect Dylan is commendable.”

14. Conclusions on Dylan

The decision reads: “The evidence suggests that it is unlikely that [Allen] could be successfully prosecuted for sexual abuse. I am less certain, however, than is the Yale-New Haven team, that the evidence proves conclusively that there was no sexual abuse.” The judge further concluded that Dr. Schultz’s and Dr. Coates’s opinions “may have been colored by their loyalty to Mr. Allen,” and that the report provided by the Yale-New Haven team was suspect due to the “unavailability of the notes,” which were “destroyed prior to the issuance of the report,” and the doctors' “unwillingness to testify at this trial except through the deposition of Dr. Leventhal,” a pediatrician on the team, “resulted in a report which was sanitized and, therefore, less credible.” The judge concludes: “We will probably never know what occurred on August 4, 1992. The credible testimony of Ms. Farrow, Dr. Coates, Dr. Leventhal, and Mr. Allen does, however, prove that Mr. Allen’s behavior toward Dylan was grossly inappropriate and that measures must be taken to protect her.”