A considerable amount of ink has already been spilled attempting to explain both the critical acclaim and the public backlash to the DAU art project, and the fourteen films generated by this initiative. Two chunks of the project—DAU. Natasha and DAU. Degeneration—were screened at the Berlin Film Festival in late February. Now that an assortment of the films that resulted from a wildly ambitious, but perhaps hubristic, artistic experiment are available for online streaming by the public, it might be a propitious time to reexamine why DAU, in all of its complex manifestations, has been favorably received by most critics while simultaneously proving scandalous for its supposed violations of political and moral rectitude, at least some of which might be more imagined than real.

The brainchild of Russian filmmaker Ilya Khrzhanovsky, the DAU project is not easy to sum up succinctly. It’s usually claimed that Khrzhanovsky initially set out to make a straightforward biopic based on the life of the Soviet scientist Lev Landau (referred to by his nickname, Dau, within the films), who won a Nobel Prize for his work in theoretical physics in 1962. Nevertheless, this multimedia endeavor soon mushroomed into a sort of artistic laboratory that endeavored to both mirror, and creatively distort, the preoccupations of the Soviet elite, as well as those who catered to their needs, within the hermetically sealed confines of the Landau Institute for Theoretical Physics.

Journalists have been predictably fascinated with the “immersive” quality of DAU, which was shot from 2009-2011 in disparate European locations, even though the bulk of the project was filmed on a huge set, supposedly the largest ever constructed in Europe, in Kharkiv in northern Ukraine. Thousands of primarily non-professional actors, as well as a handful of art-world celebrities such as Marina Abramović and Peter Sellars, were encouraged, in an avant-garde twist on Method acting, to fuse their own personalities with the lives of their characters, denizens of a totalitarian universe that strangely mirrors tendencies that still endure in post-communist societies in the East and are certainly percolating at the moment in the post-liberal West. Some of these untrained actors lived in the Institute during filming.

In a characteristically breathless account, Steven Rose in The Guardian insisted that the production yielded “less of a film set than a parallel world: a functioning mini-state, stuck in the mid-20th century and sealed off from the modern world.” In an equally bemused account of the production process, GQ’s Michael Idov described an almost Philip K. Dick-like simulation of the Soviet era in which participants were “encouraged” to snitch on each other and renegades were kept in line.

Journalists, Rose among others, keep returning to the same analogies—efforts to label the project a Soviet-style “Truman Show” or a gargantuan equivalent of a big-budget Hollywood movie made by obsessive directors such as Cimino or Coppola aimed for precision but don’t quite hit the mark needed to categorize an enterprise that was essentially unclassifiable.

Dark rumors that supporting players were being exploited on set proliferated while many were disturbed by the involvement of an actual neo-Nazi, Maxim Martsinkevich, who plays the most despicable protagonist in DAU. Degeneration. A piece in The Telegraph by a participant wondered if a critique of Stalinism had itself congealed into an exercise in Stalinism and reported rumors of on-set sexual abuse that would subsequently resurface at the Berlin Film Festival—while paradoxically concluding that the shoot was an “awe-inspiring” experience.

These contradictory accounts proved useful in publicizing the first public screenings of the films at two theaters in Paris, as well as an exhibition inspired by the project at the Centre Pompidou, in 2019. Perhaps as a savvy promotional ruse, attendees were required to submit a “biometric” application in order to purchase a “visa” for entry to the events, a gimmick apparently designed to remind spectators that they were not privy to a mere cultural happening but were being granted access to an alien artistic realm.

When DAU. Natasha and DAU. Degeneration premiered at Berlin over three months ago, the critic Carmen Gray described the project as “ethically thorny.” Yet she also argued that the controversy swirling around the films prevented many observers from judging the films on their own artistic merits. Despite favorable reviews by the majority of critics from both the trade papers and specialized film journals, five Russian journalists penned an open letter objecting to the festival’s decision to include DAU. Natasha in the competition (it ended up winning a special award for Jürgen Jürges’s cinematography) and summed up their qualms by aligning Khrzhanovsky’s agenda with that of Harvey Weinstein, a convicted rapist. They also questioned the ethical probity of honoring a film that “by its own authors’ stark admission, contains scenes of real psychological and physical violence against non-professional actors,” as well as “allegedly unsimulated sex between actors seemingly under the influence of alcohol.”

The Russian journalists were particularly perturbed by Natasha’s concluding scene, in which a KGB officer and the future head of the institute, Vladimir Azhippo, rapes the title character, a canteen waitress, by forcing her to insert a cognac bottle into her vagina. Despite the claims voiced by the open letter’s signatories, Natalia Berezhnaya, the actress playing Natasha, made it clear during a festival press conference that she was aware that the scene was part of a fictional performance, was a willing collaborator, and squashed accusations that she was a real-life victim of sexual abuse.

How is one to make sense of conflicting views of this film, which alternate between claims that non-professional actors were subject to physical and psychological abuse and assertions that DAU. Natasha merely belongs to a tradition of European art films screened at festivals that foreground unsimulated sex? Although the aggrieved Russian journalists don’t provide documentation for their claims of on-set sexual abuse, their insinuations no doubt reflect journalistic accounts that took Khrzhanovsky to task for reinforcing a hierarchical, even dictatorial pecking order during the production and unearthed evidence that he pried into female performers’ sexual histories during the casting process.

The Daily Beast contacted Khrzhanovsky via email through a representative and asked him to comment on some of the more incendiary accusations lodged by the Russian journalists.

He replied that “modern society now strives for a new form of impeccable morality. Commentators have good intentions; they want to protect people. While trying to protect Natasha Berezhnaya, they are continuing to torment her with these accusations. Despite the fact that I didn’t torment Natasha Berezhnaya, journalists who sincerely wish her well are hurling these accusations. Most people, especially journalists who protest against films, have good intentions, but they also have the potential to destroy lives.”

“Now Natasha and other DAU members, who used to be proud of their participation in the project, find themselves in a situation where they are constantly forced to justify themselves and prove that they were not tortured or experimented with. And no matter what Natasha says, no matter how many interviews she gives that try to persuade people that no one has raped her, everyone will still fight for the rights of an abstract Natasha and end up ruining the real life of Natasha Berezhnaya. This humiliates the project’s participants and causes me anxiety because it is unfair to them and to the project.” (Berezhnaya could not be reached for comment.)

In order to disentangle the thicket of rumors and hints of scandal that continue to envelop the DAU project, I carried on an email correspondence with Boris Nelepo, a Moscow-based journalist and the artistic director of the Spirit of Fire International Debut Film Festival. Nelepo argues that, although the process devised by Khrzhanovsky on the set of the DAU films has been “compared to reality-TV shows such as Big Brother,” these comparisons are entirely fallacious. Nelepo emphasizes that reality-TV shows are “all predicated on the presence of hidden cameras” while the DAU features were “shot exclusively on 35mm…it is almost impossible to forget that you are an actor when you’re in front of at least three people, including the technicians changing the camera rolls and shooting the action.”

Swallowing the films’ playful attempt to blur history and cinematic fictionalization, some spectators seemed to think they are viewing “undiluted reality.” Of course (spoiler alert), “all of the protagonists are killed at the end” of DAU. Degeneration and “we’re shown their corpses,” even though it’s apparent to all audience members that “this is a movie, no one has been killed, and the harrowing sense of reality is the product of a specific improvisational method.”

In responding to the protests raised by the Russian journalists’ open letter, Nelepo maintains that the discussion around the films has become “toxic, even radioactive.” While he has “no animus against people who dislike the DAU films,” he reports that after writing on Facebook that he considered DAU. Degeneration “the strongest film of the entire festival,” commenters branded him a “pervert,” “a sick person,” and incorrectly assumed that he was a friend of the director. For Nelepo, this proved “humiliating… the people condemning the film conceive of it as “a snuff movie, want to ‘cancel’ it; the festival programmers and film critics who defend it are pilloried as co-participants in a crime.” It should also be noted that, in Russia, four of the DAU films have been stigmatized as “pornographic propaganda,” whatever that is, by the state. Perversely enough, supposedly “left-wing” attempts to bar these films from festival screenings coincide with the official diktats of reactionary censors.

While Nelepo is wary of concluding that DAU is “an absolute masterpiece,” he believes the project “is totally unprecedented in the history of Russian cinema.” That being said, he deems DAU. Natasha the “weakest film of the cycle.” He dislikes the ending of the film with its now-infamous “torture” and “rape” because Natasha’s ending corresponds to the conventions of certain festival movies, replete with the kind of pseudo-provocation that frequently surface in prestigious arthouse films.

Nelepo compares its shock tactics with some of the Romanian director Cristian Mungiu’s features, but one might well also invoke some of the more manipulative and less artistically successful scandal-mongering films of Lars von Trier. Even though the protracted conclusion of Natasha might conform to arthouse clichés, the earlier scenes are more rooted in an almost documentary-like chronicle of Natasha’s fraught friendship with her assistant Olga and her increasingly passionate affair with a French scientist.

During a press conference at Berlin, Khrzhanovsky characterized the world of DAU as an “intermediary” realm in which an ostensible desire to replicate a previous epoch is accompanied by quasi-surreal embellishments that depict honest “emotions” which coexist with deliberate historical falsifications. This kind of ambition is more apparent in Degeneration than in the relatively small-scale Natasha. Set in the years 1966-1968, more than ten years after Natasha’s narrative unfolds, Degeneration is an epic reimagining of Brezhnev-era Soviet society that intersperses historical concerns with testimonies from a host of contemporary personages playing themselves: quantum physicists, brain specialists, performance artists and, of course, neo-Nazis. Reinforcing the truism that films about the past are actually about the present, the film implicitly posits a convergence between the repressive nature of state socialism and the right-wing populism that currently looms over much of Europe and the United States. Another potent political theme is driven home by a rabbi’s (Adin Steinsaltz, an Israeli Talmudic scholar) voice-over narration that punctuates the film. Asserting that communism is actually a surrogate religion and that Karl Marx’s work announced the arrival of a “messianic religion,” his musings recall the Christian philosopher Nikolai Berdyaev’s assertion that “Communism persecutes all religions because it is a religion itself.”

Western viewers will of course be most stunned by the characters’ sexual hijinks; Degeneration’s decidedly melancholy orgies go against the grain of our preconceived notions of Soviet-era puritanism. The film’s bacchanalian interludes are indebted to Landau’s unorthodox espousal of “free love,” a now-musty creed that brings to mind activities more reminiscent of the Kinsey Institute than a scientific think tank with ties to Soviet apparatchiks.

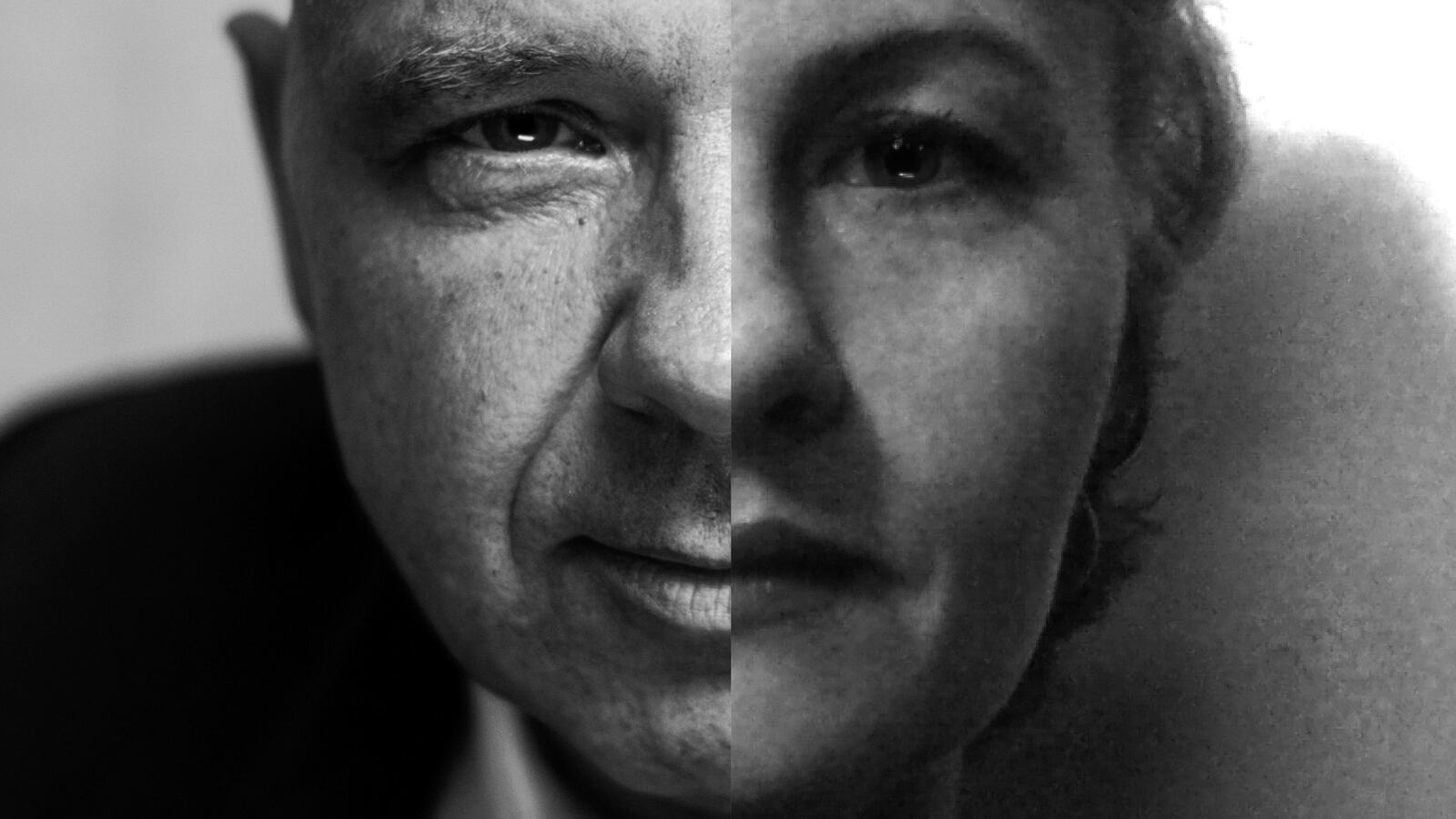

Ilya Khrzhanovsky

Thomas Niedermueller/GettyNot surprisingly, the scenes featuring the brutal antics of Maxim Martsinkevich, a living, breathing neo-Nazi who now resides in a prison, and his fascist cronies (not to mention these hooligans’ onscreen slaughter of a live pig) have inspired a certain amount of critical bewilderment and outrage. Still, even a perfunctory viewing of the film confirms that Steinsatz’s Jewish humanism is meant to triumph over Martsinkevich’s reactionary nihilism. (Khrzhanovsky is Jewish himself.) In this regard, the casting of James Fallon, a distinguished American brain specialist, is a key element of Degeneration’s polemical thrust. Fallon is known for his astonishing discovery that he possessed the genetic profile of a full-blown psychopath. In Degeneration’s absurdist vision, psychopathology has become normalized and is in fact the ruling ideology. As Nelepo points out, “Neo-nazis represent absolute evil in the film. Choosing a neo-Nazi to play a Nazi is part of an artistic experiment. It seems arrogant to dictate what artistic choices a director is allowed to make.”

When asked about the moral and aesthetic rationale of hiring an actual neo-Nazi to play this pivotal role, as well as a scene with Martsinkevich that culminates in the slaughter of a live pig, Khrzhanovsky replied:

“In Degeneration we showed the mechanism of how Nazis come to power in great detail, we showed how the intelligentsia accepts it. When I was planning the film, I did not know I was going to shoot neo-Nazis in DAU, but this unexpected decision was very important. I do not regret it. As a general point, I would have liked to show Degeneration in countries where far-right parties are now gaining more and more votes. It may seem to us that the Nazis are alien presences, but in fact they are very close to our reality. This is the hellish story of what happened in Germany. The Nazis did not arrive from Mars, they lived among the Jews. Just at some point there was a U-turn. This is a story about discerning this U-turn in time to review its mechanisms.”

For Khrzhanovsky, “slaughtering a pig is a demonstration of the ideological mechanisms that we showed in the film. Forgive me, animal defenders, but the sacrifice of the pig in Degeneration was not particularly cruel. It was not much more cruel than the bull slaughtered in Coppola’s Apocalypse Now. The pig is a blatant manifestation of a nightmare called Nazism.”

As if accusations of sexual abuse and being soft on fascists weren’t enough, Khrzhanovsky is embroiled in several other DAU-related controversies that are difficult, if not impossible, for non-Russians to evaluate dispassionately. The director has been criticized for acquiring the major financing for the films from Sergey Adoniev, a Russian oligarch and philanthropist. Investigated by the FBI in 2019 for suspicion that he trafficked a metric ton of cocaine, Adoniev is said to have ties to circles close to Vladimir Putin. When asked to comment on some commentators’ raised eyebrows concerning Adoniev’s funding of the project, Khrhzanovsky defended Adoniev effusively: “Sergey is an extraordinary and brilliant person. Without Sergey’s support, DAU and many other Russian cultural projects would have been unthinkable. He’s told me that he supports unique projects that no one else would subsidize.”

In another brouhaha that’s difficult for outsiders to assess, Khrzhanovsky has recently been appointed the artistic director of the Babyn Yar Holocaust Memorial Center in Kiev, and his plans have raised some hackles. Perhaps predictably, his appointment has drawn fire from critics who associate him with charges of exploitation and sexual abuse. Some are fearful that the museum, which commemorates one of the most horrific massacres of the Second World War, will suffer the fate of a “Holocaust Disneyland.” The site of a notorious massacre where 34,000 Jews were murdered by the Nazis in 1941, Babyn Yar’s legacy remained a sore point for Soviet bureaucrats, who wanted to emphasize the “universal” instead of the specifically Jewish resonances of the event in the post-World War II era. The Soviet authorities attempted to eradicate the historical memory of the genocide, which didn’t become part of the national discourse until the dissident poet Yevgeny Yevtushenko published his poem commemorating the Jewish dead, “Babi Yar,” in 1961.

Much of the uproar spurred on by Khrzhanovsky’s involvement in the Holocaust memorial involves plans for a proposed interactive exhibition, leaked to the press, that would separate museumgoers into “executioners, victims, and collaborators.” In certain respects, these plans seem to echo the DAU project’s attempt to immerse contemporary spectators into the realm of the past and its experimental aesthetic, even though applying this concept to the agenda of a solemn memorial seems somewhat dubious, to say the least.

Khrzhanovsky gave The Daily Beast a detailed account of his still-evolving plans for the Babyn Yar Memorial Holocaust Center: “What happened in Babyn Yar is a terrible tragedy for Jews, Ukrainians and all of humanity. These events also touched my family. I am the son of a Jewish woman, who miraculously managed to escape from Ukraine on the eve of mass destruction. For me, the feelings of people who survived the Holocaust, the descendants of the deceased and survivors, are extremely important. I myself am among them and feel responsible for the sensitivities of the survivors. The memory of the fallen is a very important part of the collective memory of the people, and appropriate ways of working with it are necessary.”

“The methods that I used in the DAU film project are fundamentally different and not suitable for evoking the memory of this tragedy. The experimental DAU project is concerned with degradation of the Soviet system and the trap in which the Soviet people found themselves. Responsibility for the tragedy of Babyn Yar lies entirely with the totalitarian regime of Nazi Germany and there can be no disagreement here. And the project of the Memorial Center cannot be determined singlehandedly; it can only be created collectively in discussion with the public. Much of this work has already been done and reviewed by leading Ukrainian and international scholars.”

“Unfortunately, fragments of a working presentation, in fact the draft that I sketched in the fall of 2019, were anonymously transmitted to the press and are now manipulatively used to criticize me and the project as a whole. I repeat that the presentation was nothing more than a working note created before I took office. I share the indignant reaction to these materials in the American, Ukrainian and Israeli press that arose in response to the appearance of these fragments on the Internet. I did not plan and do not plan anything resembling an amusement park or ‘Disneyland’ on the site of the tragedy. I consider this blasphemy.”

Finally, in a rather jaw-dropping twist, Ukrainian prosecutors began an investigation in April into the alleged “torture” of children on the set of DAU. Degeneration. Mykola Kuleba, Commissioner of the President of Ukraine for Children's Rights, expressed dismay that children from orphanages were recruited for the shoot and appeared as subjects of psychological experiments in a two-minute scene in the film. Kuleba requested that the participation of the children in the film be “investigated by the police.”

When asked about these serious accusations, Khrzhanovsky denied them categorically: “After watching the movie on our official website, a disgruntled person posted that Degeneration conducted actual experiments on children from orphanages. This post inspired a criminal investigation. This scene with children was shot in less than two hours; in the film it takes several minutes. Of course, we had all the permissions from the authorities of the Kharkov region and from the management of the orphanage. There is a whole protocol outlining how such scenes should be filmed.”

“The childrens’ guardians arrived before the shoot and checked the condition of the room, the temperature, and assessed what might happen. Employees of the orphanage were not only present with the children at the site, but also were in the scene itself: they can be seen on the screen. We invited the orphanage staff, to ensure that the children would not experience stress. All this absolutely corresponds to all legislative and universal norms.”

“It was a much more arduous and time-consuming process to obtain, and negotiate permission, to borrow children from orphanages than it would have been if they resided in private homes. It is very important not to confuse artistic representation and the means devised to create it. When audiences notice wires and other medical devices in the frame with babies and we hear their screams, you must remember that the shooting of a feature film involves the imposition and amplification of sound and, of course, the use of other professional ‘special effects.’ Otherwise, if the presence of the corpses of all the main characters at the end of Degeneration was taken at face value, we’d have to investigate actual massacres. For this reason, the reaction to the scene is absurd.”

In addition, Khrzanovsky noted that James Fallon, the well-known brain specialist featured in the scene in which the children undergo these fictional experiments, gave an interview in which he commented on how nurses that accompanied children to the set treated their charges with great tenderness.

In many respects, the furor over this brief scene pinpoints the tendency of the DAU films to literalize the blurred boundaries that have emerged in recent years between fiction and documentary. On the one hand, there is the tendency of observers to confuse representation of atrocities with atrocities themselves. On the other hand, it is also difficult to refute the notion that Khrzhanovsky’s desire to imbue fictional premises with a hyper-real, immersive intensity, his conception of cinema as a vast laboratory in which actors merge their own identities with their characters, often inhabits an ethically grey area. In our correspondence, Khrzhanovsky acknowledged his debt to the Russian director Anatoly Vasiliev’s innovative production of Luigi Pirandello’s Six Characters in Search of an Author. Pirandello’s work embodies the modernist predilection for fusing art and life, a tradition that is discernible in a Russian theatrical tradition that can be traced back to the non-naturalistic experiments of Vsevolod Meyerhold that emphasize extreme physicality. For skeptical observers, the question remains as to whether Khrzhanovsky’s techniques transgress ethical red lines or continue a tradition of legitimately audacious artistic experimentation.

Whatever one’s ultimate judgment, it’s inarguable that the DAU project exemplifies a comprehensive attempt to come to terms with the legacy of totalitarianism. (It should also be noted that some of the films that have so far received less attention from the press than the Berlin premieres—e.g. DAU. Katya Tanya and DAU. Three Days—are considerably more restrained and less sensationalistic.) As Khrzhanovsky concluded at the end of our email correspondence: “The structure of totalitarianism permeates the genetic code of human beings and the development of this virus suffuse all our souls. In this sense, totalitarianism is the same virus as the pandemic raging today and its laws are always the same. I’m convinced of that.”