A grim queue of white vans drove from Yarnell, Arizona, to Phoenix on Monday, transporting the charred bodies of 19 firefighters, 14 of them in their 20s, who had perished during a deadly and unpredictable wildfire the day before.

As investigators struggle to determine what exactly went wrong—how nearly an entire crew of elite firefighters could die in one blaze—residents of the tiny town are left to grapple with shock, loss, and grief.

The fire began Friday, officials said, and most likely was caused by lightning on Yarnell Hill, which overlooks the small community of about 700, many of them retirees. By Sunday, the shifting winds of a monsoon storm drove the flames toward the town. As the flames bore down on their homes, frantic residents of the Glen Ilah neighborhood released horses, pigs, chickens, and other animals from their pens and fled for their lives, transporting walkers and wheelchairs in the backs of their pickup trucks.

"I don't watch movies much, but it was like being in a very bad movie," says Vicki Velasquez, whose house was burned to the ground. "The flames were orange, and it was impossible to judge how close they were. My brain is still a little cloudy. I'm still in shock."

As residents fled, the Granite Mountain Interagency Hotshot Crew, a tight-knit group that included full-time and seasonal firefighters who worked on the front lines of fires across the United States, was in danger.

Fire officials lost contact with the crew around 4:30 p.m. Sunday, said David McAtee, a spokesman with the county’s Yavapai Emergency Operations Center. A helicopter crew spotted their bodies a short time later. “It’s one of those freak incidents where the wind split the fire and flanked them on both sides before they had a chance to get out of there,” McAtee said. “It eliminated their escape.”

It was the deadliest day for firefighters in the U.S. since September 11, 2001.

As of Monday evening, the fire was still raging out of control, having burned more than 8,000 acres, and efforts continued to determine how such a tragedy had occurred.

"Whatever the situation was that took place [with the firefighters' deaths], we haven't been able to explain yet, but there's an investigation taking place," Don Fraijo, the fire chief of nearby Prescott, said in a press conference on Monday.

Many details remain unclear. As the fire bore down on them, all the firefighters deployed a safety device called a fire shelter—a foil-lined, heat-resistant bag meant for firefighters to climb into as a last resort. Some of the bodies, though, were found outside the shelters.

The U.S. Forest Service made carrying fire shelters mandatory in 1977 after three firefighters who weren’t carrying shelters were killed in Colorado. Between 1977 and 2007, 275 firefighters have been saved because of the shelters. But 20 firefighters have perished after deploying them.

“Fire shelters are a last-ditch effort, and you hope the fire passes quickly over,” says Mike Archer, a California wildfire consultant who is not involved with the Arizona investigation. “It will deflect the heat for awhile, but if the fire doesn’t get past you fairly quickly, you will just roast inside of it. That’s why it’s the last-ditch effort. It helps, but it certainly is not the ultimate protection. You won’t last long in a tinfoil tent in those conditions.”

“They cooked to death,” adds Archer. “There’s a limited time you can stay in there and be safe.” Archer says the shelters are designed to be folded up so you can carry one with your pack. “It’s not a silver bullet if you get caught in a burn-over. You have a better chance with a shelter, but not a guarantee.”

Typically, Archer says, a crew like the one that died in Yarnell is sent to the front lines of a blaze with a chain saw and a Pulaski (a combination of ax and hoe) to clear the area of brush. “They want to get rid of the combustible material and get down to something that can’t burn,” he says. “They’ll try to make a line that will parallel the fire and will stop the fire from spreading around the area.”

Archer says fire officials will most likely try to determine if there was anything they could have done to save the firefighters, all of whom died except one. “If there had been an air tanker nearby, they might have been able to drop on the area,” he says, referencing the aircraft capable of dropping large amounts of water directly on top of out-of-control blazes. However, windy conditions or smoke may have prevented that from happening.

McAtee says he doesn’t know if fire officials attempted to drop retardant to save the firefighters. “We know they dropped the [retardant], but we don’t know when in the timeline it happened. They will do an investigation, and details will come out later.”

Only about 100 Yarnell residents remained in the charred town Monday. One was Chuck Tidey, a retired helicopter pilot who fought in Vietnam and felt it was his duty as the president of the chamber of commerce to stay with the ship. He sat in the library and watched helplessly as propane tanks that fueled homes exploded in "one black puff of smoke after another." (His home was untouched.) Tidey then watched cadaver dogs and firefighters pass through town on a grim trip to recover the fallen firefighters’ remains.

On Monday afternoon, officials released the names of the dead.

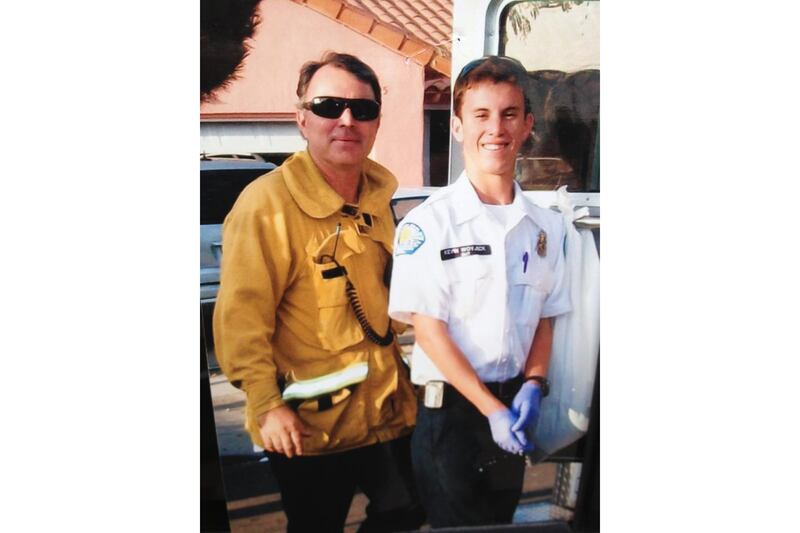

One of the firefighters who lost his life in the inferno was 21-year-old Kevin Woyjeck, whose father is a Los Angeles County firefighter. “He was working very hard to follow in his father’s footsteps,” says Los Angeles County fire inspector Keith Mora. “He was a great kid. He always had a smile on his face.”

Joining the Prescott crew was a dream come true for the former Los Alamitos High School track star, lifeguard, EMT, and top athlete. “It is a physically demanding job,” says Mora. “It’s a young person’s job. You do a lot of hiking. You can be out there for months at a time. You have to be self-motivated and in incredible shape. They have the same physical-fitness levels as athletes.”

“He was laser focused on trying to achieve his career as a firefighter,” says Bill Weston, the director of operations of Care Ambulance, who worked with Woyjeck. “Bottom line is, he really wanted to help people.”