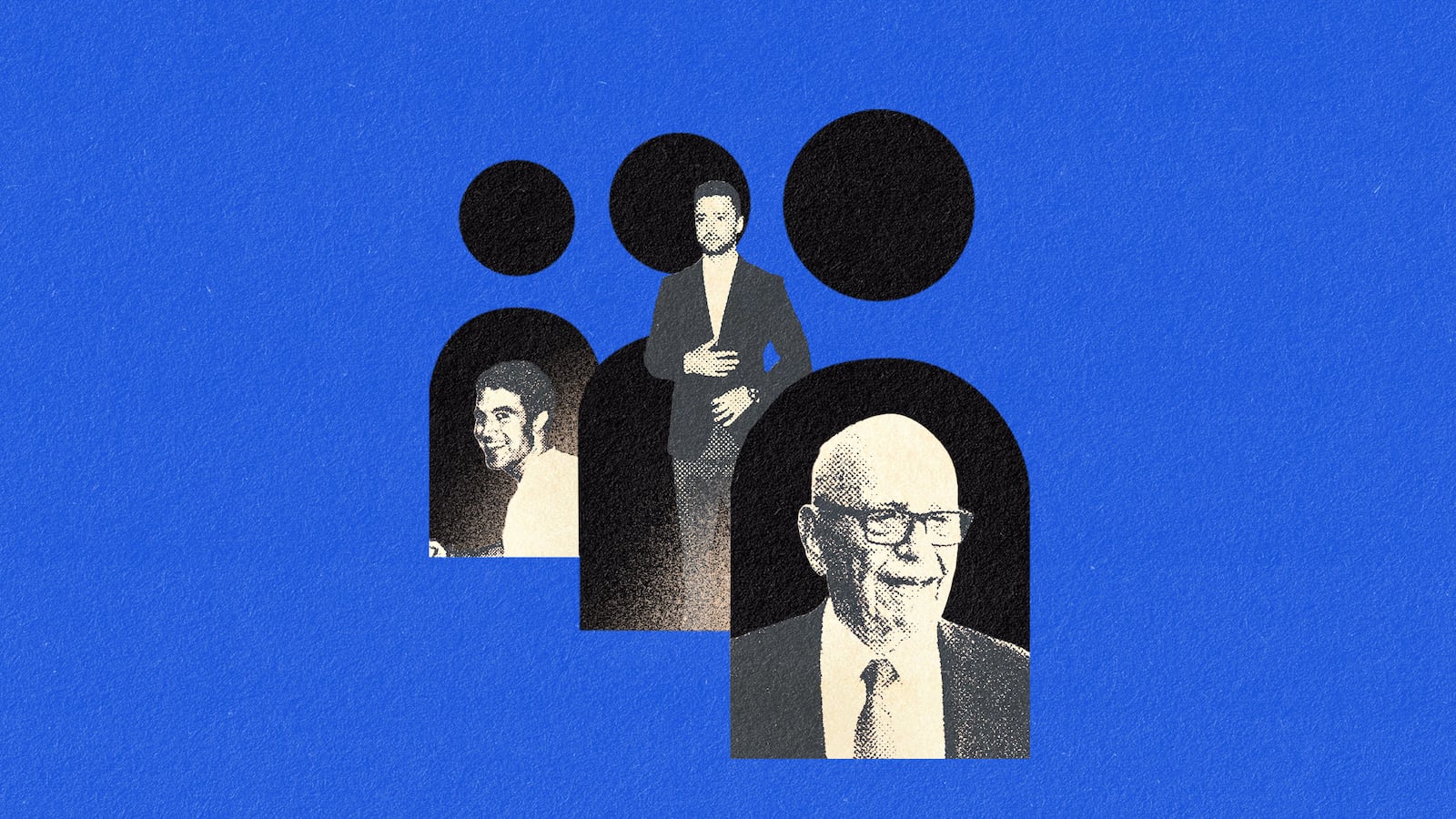

In 2003, UCLA dropout and former punk singer Tom Anderson and marketing executive Chris DeWolfe co-founded MySpace, the best social media website ever. By 2005, MySpace had overcome Google to become the most popular website in the world, and was purchased by Rupert Murdoch’s News Corp for $580 million.

Murdoch immediately struck an advertising partnership with Google for $900 million over three years. But the site began to buckle under the weight of the deal, as well as underlying infrastructure that badly needed an update. As the website became slow to load and filled with spam, users began to flee and Murdoch’s predictions that the site would generate $1 billion in revenue proved to be incorrect. Facebook overtook MySpace in 2008, and DeWolfe and Anderson left the following year.

Murdoch brought in new leadership to right the ship. They had their work cut out for them.

This is an excerpt from Top Eight: How MySpace Changed Music, out this week via Chicago Review Press.

--

A lot of things can be said about Rupert Murdoch and the corroding effect he had on the world at large. But you don’t become one of the richest men in the world if you don’t have a pretty firm grasp on ruthless capitalism, and at some point it became clear to him that it was time to stop throwing good money after bad.

After purchasing MySpace, Murdoch had reportedly been distracted by purchasing Dow Jones and the Wall Street Journal and figuring out how to integrate them into News Corp. But eventually, he became aware of the scope of MySpace’s decline. Murdoch had recently installed the Irish-born Chase Carey, a longtime News Corp executive who’d been away at DirecTV during the MySpace acquisition, as News Corp president and COO. Described by Reuters as “a straight-talking, dollars and cents kind of executive whose only obvious extravagance is his remark- able handlebar mustache,” Carey had no particular affection for MySpace and told Reuters it had “quarters not years” to turn things around.

That attempt to turn things around took the form of a relaunch in October of 2010, when the site’s monthly visitors had dropped to around sixty million. (It had been losing a million visitors a month for the past two years.) Rather than fixing problems incrementally, MySpace CEO Mike Jones had decided to save it all for one last push. Instead of competing with Facebook directly, Jones decided to focus on MySpace’s reputation as the place where music fans and other pop culture vultures found new artists and traded recommendations.

In retrospect, it seemed like a way to remind people that while Facebook may have been less chaotic, it also had much less personality. The new, cleaned-up feed got rid of the old “a place for friends” logo and operated on a grid system that made it easier to share and organize your favs. It was also easier to sync up with your Twitter and Facebook accounts and for artists to install third-party applications such as the fundraising tool Pledge Music. The relaunch even tried to stay true to the site’s discovery ethos with the feature Hunted Real Time Radio, which played the most popular MySpace artists of the last sixty seconds.

It still wasn’t enough. Four months later, MySpace’s unique visitors had fallen to thirty-eight million, a shocking 30 percent drop. In January of 2011, five hundred employees were laid off, a reduction of 47 percent. Finally, running out of patience, Murdoch began looking for someone to pawn off MySpace on. DeWolfe, backed by the investors Austin Ventures, expressed interest, as did Anderson, backed by Criterion Capital Partners LLC, and so did the Chinese Internet holding company Tencent. News Corp also approached Vevo, an online music video site jointly owned, at the time, by Universal Music, Sony Music, and Abu Dhabi Holdings, about a possible venture, and the video game company Activision Blizzard Inc. was also in the running.

Eventually, MySpace was purchased by Specific Media, a digital ad network, for $35 million, less than the $100 million that News Corp was hoping for, and much, much, much less than the $580 million News Corp had originally paid for it. Clearly, Murdoch was willing to take a steep loss just to be done.

Specific Media was founded in 1999 by brothers Tim, Chris, and Russell Vanderhook, from Irvine, California. The company originally sold advertising space for websites. It later moved into harvesting users’ browsing history, demographic data, and other unique information for targeted advertising. Specific wasn’t a well-known company, so the Van- derhook brothers decided to bring in some high-profile help. They also laid off half of the remaining five hundred employees.

In The Social Network, David Fincher’s 2010 film about the battle over who exactly created Facebook, Justin Timberlake played Napster cofounder Sean Parker. Perhaps that experience unlocked something in Timberlake, because in 2011 Specific Media chief executive Tim Vander- hook said that the pop star turned Serious Actor would help “lead the business strategy” for the relaunch, with a focus on bringing the creative community on board. This seemed to mostly mean the alt-pop artist Kenna, whom Timberlake brought on as a consultant. Vanderhook also said Timberlake had put his own money into the sale for a minority stake but wouldn’t specify how much. But people who actually worked at MySpace doubt the official story. “These guys were not afraid to throw money at this purchase that they had,” says Kevin Hershey. “So they threw a million dollars to Justin Timberlake and said, “Hey, can we say that you’re an investor?”

Vanderhook talked a good game, telling the Hollywood Reporter in 2012 that the newly relaunched site would be a “a social network for the creative community to connect to their fans.” He said there would be a feature wherein fans would be able to be featured on their favorite art- ists’ page, and that after the initial campaign wore down, the site would “eventually reach out to undiscovered talent and music fans.” Along the way, MySpace officially became stylized as Myspace.

SEAN PERCIVAL (VICE PRESIDENT, ONLINE MARKETING): Murdoch was saying we were going to do a billion dollars in revenue. We weren’t even close to that. When the bar was that high, the team probably realized, “Oh crap, we’ll never get there.” But they still sacrificed the product a lot trying to.

BÍCH NGỌC CAO (MYSPACE MUSIC EDITOR): After it was purchased by Specific Media, it wasn’t worth anything, because the user base was old and also could not be ported anywhere.

SARAH JOYCE (SENIOR DIRECTOR, CORPORATE COMMUNICATIONS): Everyone who was a MySpace Music person was like, “Can we just become our own thing?” And our only focus was artist tools and connecting artists and fans and just maybe selling merch and tickets and continuing to evolve that product and stay very narrow on that. If they were iterating with that in mind and said, “Let’s cut the crap. We’ve lost the social element of this. We don’t need a TV vertical. Let’s double down on music,” then I would argue MySpace could have kept up and would have been a Spotify competitor. But it didn’t. It crashed and burned fast.

KEVIN HERSHEY (DIRECTOR, PARTNER AND LABEL RELATIONS): MySpace being for sale was not a shock. It was expected in my world, because I was sitting here, hearing top-level numbers based on what MySpace music was doing and generating.

PERCIVAL: So the week I started, they actually had laid off, I think, five hundred, six hundred people maybe. So I walked into an office where entire floors were empty. And the first meeting I had with the marketing team, the best way to describe it is depression. They were defeated. You could just see it in their eyes. Half of them had already checked out, and they had just lost half of their department. So I think there was this concern of like, when am I next?

JOYCE: The hardest thing to do is say no. I’d argue they were the first Internet social company to achieve that level. It was phenomenal. I remember being at Comcast before Fox bought it, and I remember telling my boss, “Oh, we should buy MySpace.” There was no precedent for that kind of level of explosive growth from both the culture and actual business numbers, driving traffic and being the first of its kind. So they said yes to everything. They lost their way.

PERCIVAL: They felt that we have to eliminate all these silos and get more collaborative. Rupert Murdoch even came to the office. I don’t know if he ever came to the office prior to that year. It’s a bit like Darth Vader coming on the bridge.

COURTNEY HOLT (MYSPACE MUSIC PRESIDENT): At that time, music was eating MySpace. MySpace as a social network was less valuable to consumers, but the music part of the MySpace business was growing. So MySpace was shrinking, music was growing. And basically the site that we relaunched was almost entirely rooted in music and culture. And it was the right thing to do, but it was probably just too late. And ultimately we were still trying to meet the needs of commercial deals that had been done on the advertising side.

JOYCE: We had two CEOs, and one came from a content entertainment background, the other one came from a tech background. A lot of money, a lot of ego. No one had really had a clear direction. And you got to move before the world moves.

PERCIVAL: We were hemorrhaging so much cash at that point. There were so many liabilities with vendors. I don’t know what we were burning per month. I would assume it was at least $10 million. So I wasn’t too surprised. I was surprised (it was sold to) such a small company. I was also surprised that it was essentially the same thing as eUniverse and these other things, because that’s kind of what they were just doing. They just wanted a lot of ad impressions was the way I looked at it.

HOLT: When Chris, Tom, and Jason were working on this site’s relaunch and the rebrand, that was a big pain point, because it was like, “Do you want us to make the company and the site better?” And thereby there’s all these things we have to forgo, like ad experience and delivery, in order to make the site more valuable, or “Do you want the thing off the books, because we just need to get rid of it?” And then you could have saved a bunch of time and money in rebranding and relaunching when ultimately the goal was just to get it off the books.

HERSHEY: So for them to sell it for $30 million to a bunch of bros from Orange County who were only known to us as brothers who learned how to traffic ads in their mother’s house when they were in their late teens, and somehow by doing that, created this company and it was pretty lucrative for them, we’re just kind of sitting there going, “OK, they bought MySpace for $30 million and their forte is trafficking ads. This is not going too well. Like it’s already bad, but they’re just going to turn this into a complete and total shit show.” As far as the user experience, just being bombarded by eye candy and things that you didn’t necessarily sign up for. Now, that eye candy wasn’t going to be like gifs and glitter and ponies; it was now going to be ads for FedEx. And that’s pretty much what wound up happening.

—

Michael Tedder is a freelance journalist who has written for Esquire, MEL, Variety, Stereogum, and Playboy. His book, Top Eight: How MySpace Changed Music, is available now.