A major breathalyzer manufacturer is under criminal investigation for possible forgery. Police forces nationwide have been using the same company’s machines to turn alleged drink-drivers into convicted ones—seizing licenses, imposing fines, and, in some cases, imprisoning people. Defendants have been asking judges to look under the hood of the machine that tests them, only for the breathalyzer maker to refuse to play ball.

These aren’t dystopian hypotheticals, but the reality surrounding a major supplier of breath-alcohol testing machines to cops across America.

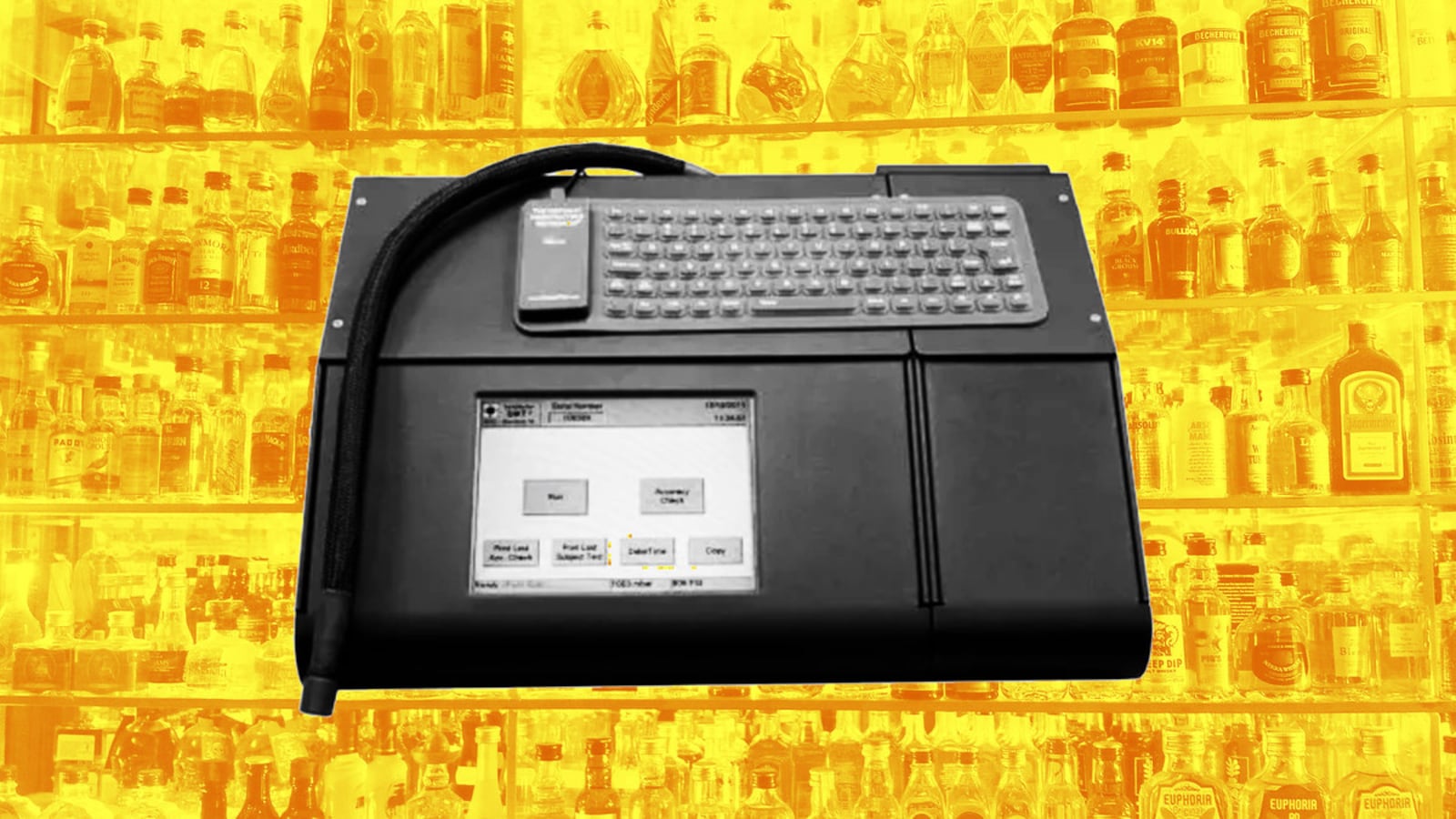

Police departments in 11 states use the Datamaster DMT, a breathalyzer the size of a printer. Cops ranging from the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department to Vermont State Police have relied on it to test suspected drink-drivers at precinct houses, where—unlike the tests done on the side of the road—results are a major factor in criminal cases.

At least they did. In January, Michigan State Police announced it had suspended its contract with the maker of the Datamaster DMT, Intoximeters, and even mounted a criminal probe into possible fraud by the company in calibrating 203 devices in the state, the Detroit News reported.

The cops alleged that two members of the company’s maintenance staff, responsible for the state’s Datamaster DMTs, falsified records on multiple occasions. Police were investigating whether the technicians forged public documents saying they had performed routine maintenance when they had not, thus allowing the machines’ accuracy to erode.

But Intoximeters’ alleged obfuscation is not confined to Michigan.

In fact, the company has resisted at least three Minnesota court mandates that police furnish the source code of its breathalyzer software to defendants, court records and interviews show. Instead of cooperating, Intoximeters has submitted documents saying it is open to police doing so—contingent on various conditions—and then opposed requests to actually follow through.

The code underpinning the Datamaster DMT and other breath testing machines has remained obscure to advocates and defense lawyers for many years, and as a recent New York Times investigation reported, the reliability of breathalyzer devices in general is suspect. But even when courts have compelled cops to reveal the code, the case of Intoximeters shows how they have nimbly evaded disclosure—and risked sabotaging their police clients.

“Unless the court order is addressed to Intoximeters itself, they’re not violating it, but the court could well order the results of a test inadmissible, which would likely result in the case being dismissed without other evidence of intoxication,” said Georgetown law professor Paul Rothstein, author of three books on legal evidence.

Intoximeters, like other industry majors, has long insisted its products are both accurate and cutting edge. In a 2013 press release announcing the company’s acquisition of the Datamaster’s original maker, National Patent Analytical Systems (NPAS), Intoximeters CEO Rankine Forrester said, “We have long felt that NPAS has the best infrared technology in the industry.”

But that doesn’t mean they welcome anyone looking too closely at the inner workings of their machinery.

“Source code is a red herring,” Intoximeters’ counsel Wilbur Tomlinson concluded in his rejection of an October 2018 court order in Hennepin County, Minnesota, after inveighing at length against the prospect: “Testing the instrument itself is the recognized method for determining whether the instrument has an issue. Any problem with the source code that could produce an erroneous result should be detectable by testing the instrument. The converse, however, is not true.”

Even as emerging techniques of modern law enforcement like facial recognition and large-scale data analysis have raised new privacy questions, the breathalyzer has remained ubiquitous in American policing. So have concerns about the precision of their measurements. A Minnesota district court judge found in 2018 that the state’s Datamaster DMT machines were falsely rounding up their results. (The company claimed the judge didn’t get how it worked.)

But critics say the legal tactics employed by the companies are just as disturbing as the machines themselves.

“The hallmark of good science is transparency, which is not what Intoximeters is doing,” said Charles Ramsay, an attorney representing defendants in the Minnesota cases. “They safeguard their software more tightly than Microsoft. It’s not because it’s something they need to do to protect their business. They do it to prevent us from discovering the fatal flaws in the software.”

<p><strong><em>Do you know about a breathalyzer company that’s fighting to keep information hidden? Do you work for a private forensics company? Contact this reporter at <a href="mailto:blake.montgomery@thedailybeast.com">blake.montgomery@thedailybeast.com</a> or from a secure device at <a href="mailto:blake.montgomery@thedailybeast.com">blake.montgomery@</a>protonmail.com.</strong></em></p>

The company does not see it that way.

“The consent order does not comply with Intoximeters’ contractual obligation with the State,” Tomlinson wrote in response to an October 2018 Minnesota court order. He asserted that a protective order meant to safeguard Intoximeters’ intellectual property was inadequate, and disputed the qualifications of the defendant’s expert, who wanted to analyze the source code.

When contacted by phone, Tomlinson declined to comment. A spokesperson for Intoximeters itself did not respond to requests for comment for this story.

The company’s fight against transparency is not unique in an industry that has traditionally worked hard to conceal trade secrets. But shoddy design and subpar maintenance by police affecting various breathalyzer brands have had dire consequences for the U.S. legal system. Judges in Massachusetts and New Jersey have invalidated upwards of 30,000 breath tests over the past year alone, according to the Times investigation.

“It’s basically the defendant’s constitutional right to defend himself and confront the evidence versus the need of commercial companies to protect information that they own,” Rothstein said. “There is a societal interest in protecting trade secrets. On the other hand, the defendant’s right is expressly in the Constitution, so that weighs very heavily.”

There may not be a clear winner—the defendant’s right to confront the evidence or protecting IP—until such a forensics case makes its way to the Supreme Court, according to Rothstein.

Until then, part of how companies like Intoximeters get away with this is simple geography: The company is headquartered in Missouri, where a Minnesota judge has no jurisdiction, and Missouri also has not signed an interstate evidence sharing agreement with Minnesota, according to a court order in the ongoing case of a Minnesotan accused of driving while impaired with a suspended license. The man’s driving privileges were revoked for months based on two Datamaster DMT tests.

But even if a technology company like Intoximeters might have legitimate intellectual property concerns, judges have shown signs of cracking down harder on attempts to keep breathalyzers secret in recent years.

Chastising the state commissioner of public safety for not providing the code in a case, Minnesota District Court Judge Andrew Pearson wrote in a December 2019 court order, “The Court points out that this request for discovery of the source code is neither surprising nor unexpected, given Minnesota’s experience with the prior model of breath testing machine or the litigation surrounding it.” The judge also suggested that Intoximeters had failed to cooperate with at least one prior Minnesota court order.

Courts have repeatedly ordered the Minnesota Department of Public Safety (DPS) to supply the source code, according to documents obtained by The Daily Beast. The contract for the Minnesota DPS purchase of Datamaster DMT machines grants the agency the right to share the source code and obligates it to do so at a court’s request, Judge Pearson wrote in December.

But Minnesota DPS won’t submit the code because, spokeswoman Jill Oliveira argued, the agency does not “own, possess, or control” it, making disclosure impossible. By the department’s logic, Intoximeters, the manufacturer of the machines and the software that runs on them, owns the code.

Pearson disagreed. “The Court concludes that the Commissioner does have possession and control of the source code for the purposes of this discovery motion,” he said. The case is ongoing.

That question—whether cops have the ability to disclose the source code of the machines they use to make cases—has divided judges. Another judge in Minnesota, JaPaul Harris, ruled in September that the state did not possess the source code after Intoximeters refused to give it up. But Harris had issued a ruling reaching the opposite conclusion in the same case back in March.

Even Intoximeters itself may not own the entirety of the code: The company said in a 2016 disclosure agreement that there are some elements of the code it does not have the intellectual property rights to share. It has left unspecified exactly who does.

Technical arguments about possession of IP aside, judges and experts say inspecting the source code of breathalyzers remains important because it allows defendants to analyze the methodology used to convict them of driving under the influence.

“If a person doesn’t get to test the evidence that’s relied on to convict them, doesn’t get to confront that evidence, doesn’t get to test the accuracy of that evidence, doesn’t get to air these questions in public, it violates their Constitutional rights to due process,” said Vera Eidelman, staff attorney with the ACLU’s Speech, Privacy, and Technology Project.

Judge Pearson seemed to agree. In the December 2019 court order, he wrote, “Given that there is no way to retest this sample on a different machine, source code review of the only analysis that will ever be performed on this now-absent breath sample is that much more crucial and proportional.”

One Minnesota forensic expert said in July went so far as to say he believed the Datamaster DMT produced “bad evidence.”

Other experts say source code analysis isn’t necessary. The National Safety Council Committee on Alcohol and Other Drugs, a safety advocacy nonprofit, issued a position statement in February 2009 asserting that analyzing the source code of a breathalyzer was not “pertinent, required, or useful for examination or evaluation of the analyzer’s accuracy, scientific reliability, forensic validity.” The Safety Council stood by the opinion when contacted by The Daily Beast for this story, and Intoximeters cited the paper in at least one rejection of a court order for disclosure.

Privacy advocates aren’t having it.

“The evidence is presented as being from an infallible, truth-telling computer,” Eidelman said. “But algorithms are human constructs that are subject to human bias and mistakes, which get in the way of their design and use.”

Drink-driving cases involving fights over source code disclosure have persisted for more than a decade. The Minnesota Supreme Court ruled in 2009 that another company, CMI, must make the source code for one of its testing devices available to a defendant. CMI initially declined, claiming the code was a trade secret, but later made it available. Meanwhile, in 2013, a North Carolina judge ruled that Intoximeters could withhold the source code from a defendant.

In 2007, a New Jersey court ruled that a defendant’s experts could analyze a breathalyzer made by Dräger, an Intoximeters competitor. The analysts described it as riddled with “thousands of programming errors,” but the court deemed the machine “generally scientifically reliable,” even if it also had “shortcomings,” according to the Times. The company claimed it quickly fixed the problems.

“There is a problem with junk science in forensics. We’ve seen numerous instances of technologies used in court getting debunked,” Eidelman said. “Public access to information about that technology and the underlying principles has been central in making those challenges successful.”

One source code inspection of a breathalyzer in Washington state made by Dräger revealed alleged flaws so glaring that the analysts commissioned by defense lawyers summed up their findings in a report titled “Defective Design = Reasonable Doubt.” The researchers said the company quashed the report with legal threats, to which Dräger replied that it was only protecting its intellectual property.

But privacy stalwarts say these quiet legal fights over breathalyzer code point to larger trends in the legal system. Those trends do not favor defendants.

“This isn’t happening only with breathalyzers,” Eidelman said. “Only more problems will be coming out as more forensic analysis becomes computerized.”