Hours after a debacle that marred Monday’s Iowa Democratic presidential caucuses, investors in a company hired to tabulate votes through a new mobile app worked to distance themselves from the company at the center of the chaos, scrubbing digital trails publicly connecting them to the firm.

The chaos in Iowa on Monday evening put a microscope on one of Democratic Party’s youngest and fastest-rising digital stars, Tara McGowan, prompting serious questions—and some conspiracy theories—about the constellation of advocacy, technology, and quasi-news organizations she's built.

“It is a pattern of fake it till you make it,” one top Democrative operative said of McGowan and her firm, ACRONYM. “You talk a big game and then sort of hope it becomes true.”

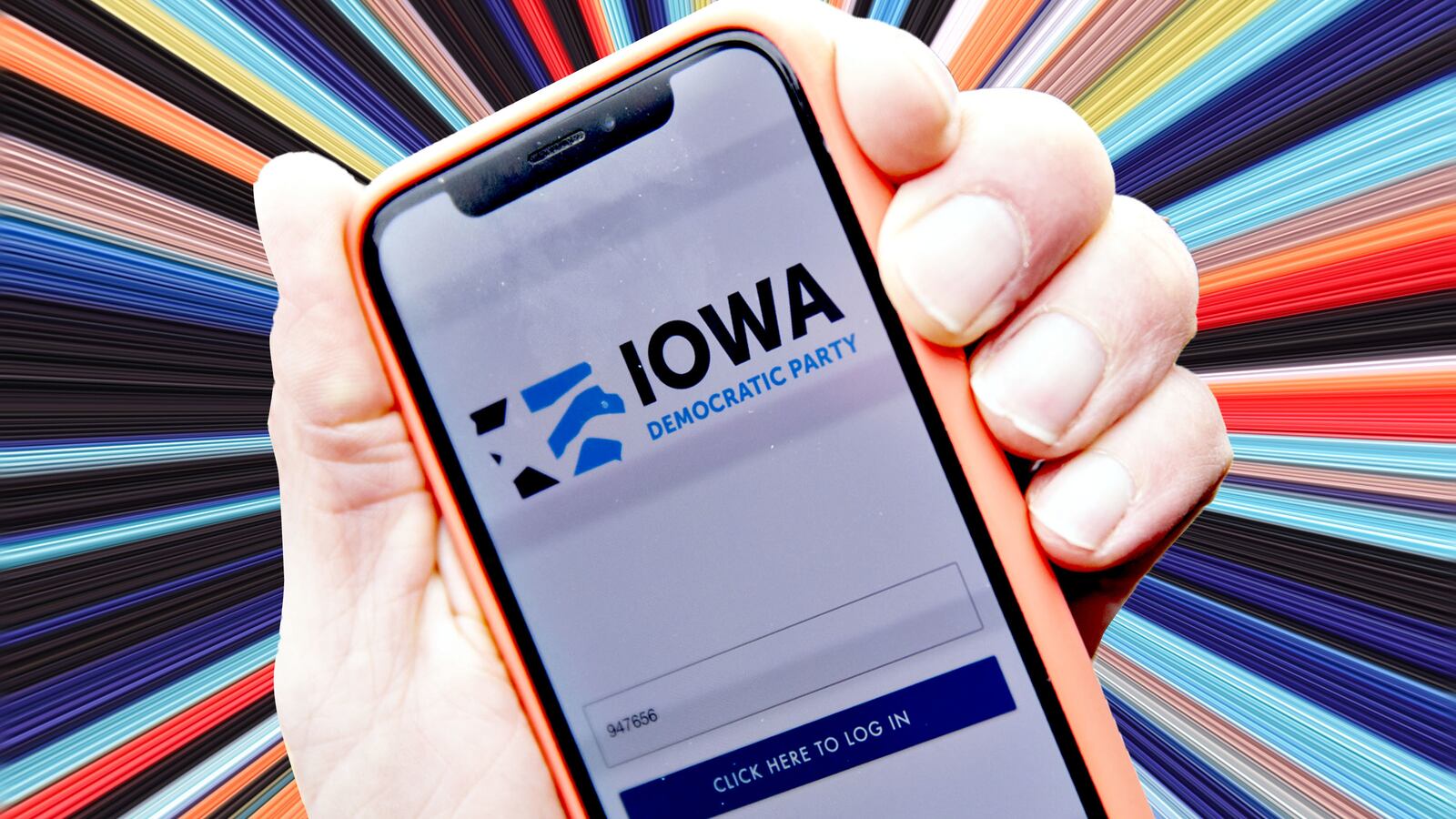

On Monday, all eyes turned to one company in McGowan’s portfolio, Shadow Inc., as Iowa precinct chairs reported serious flaws with the app it had developed to tabulate the vote. As complaints about the app trickled in on Monday, McGowan, who is the chief executive of Shadow investor ACRONYM, took to Twitter to describe her group as just that, an investor.

Not too long ago, however, ACRONYM’s website had described its relationship with Shadow in different terms. The digital, data, and text messaging vendor “will exist under the ACRONYM umbrella,” wrote Gerard Neimera, Shadow’s CEO, in a January 2019 blog post announcing the group’s investment.

McGowan herself had said that ACRONYM had “acquired” the company GroundBase, which Neimera had used to develop Shadow’s underlying technology. As of Sunday, ACRONYM’s website boasted that it had “launched Shadow.” By Tuesday, that language had been changed to say it had simply “invested” in the company.

When Shadow filed incorporation paperwork in Colorado in September, it listed its mailing address as ACRONYM’s downtown D.C. headquarters. And on the day that ACRONYM announced its investment in Shadow, McGowan excitedly tweeted a photo of the company’s staff and captioned it, “Meet the Shadow team.”

On Tuesday morning, Neimera’s blog post was no longer available on ACRONYM’s website. Between Monday evening and Tuesday morning, GroundBase was also removed from a list of portfolio companies on the website of Higher Ground Labs, an early GroundBase investor.

The swift attempts to create distance came amid intense and growing criticism directed at Shadow and ACRONYM, which did not respond to a detailed list questions for this story, in the wake of Monday night’s hectic Iowa caucuses. Iowa Democrats put out a statement on Monday evening denying reports that Shadow’s app—which had been designed as a way to report caucus results—had crashed or malfunctioned. But a number of precinct chairs said they struggled to get the technology to function as designed. Some gave up using it altogether.

The firm sought to control some of the damage in a statement released on Tuesday afternoon. "We sincerely regret the delay in the reporting of the results of last night’s Iowa caucuses and the uncertainty it has caused to the candidates, their campaigns, and Democratic caucus-goers,” the company wrote. Shadow “contracted with the Iowa Democratic Party to build a caucus reporting mobile app, which was optional for local officials to use. The goal of the app was to ensure accuracy in a complex reporting process.”

Those hiccups had already caught the attention of conspiracy theorists who noted that Shadow received tens of thousands of dollars last year from the presidential campaigns of Democrats Joe Biden and Pete Buttigieg. Those payments were simply for use of the company’s text messaging technology. Indeed, one Democratic operative from a campaign that used Shadow said that they had done so for the purposes of peer-to-peer texting, with the goal of wracking up $1 donations to help their candidate hit the donor threshold to qualify for Democratic debates.

"Our campaign used Shadow only once and on a very small scale, for sending text messages to voters about our campaign kickoff in Philadelphia,” said a Biden aide. “Our IT team expressed security concerns about it, and it ultimately did not pass our cybersecurity checklist, so we declined to use it again."

The Buttigieg campaign sent a similar statement. "We contracted with this vendor for txt messaging services to help us contact voters," a spokesperson said in an email.

But that explanation wasn’t enough to mute questions about a supposed conflict of interest: mainly, why was a company that received money from two of Iowa’s top contenders tabulating votes for all of them? As Bernie Sanders surrogate Shaun King breathlessly—and dubiously—put it: “Pete’s team funded the company that built the failed election app in Iowa.” Another Sanders surrogate, former National Nurses United chief RoseAnn DeMoro, falsely accused Buttigieg of “owning part of” Shadow’s app.

The allegations were off-target, but they were also widespread. And the Shadow recriminations soon led to a set of larger questions about ACRONYM itself: What, exactly, was the firm doing with all its time and money?

McGowan is a veteran digital operative. She’s worked for prominent Democrats including Barack Obama and Tom Steyer, and for the deep-pocketed super PAC Priorities USA. She founded ACRONYM in 2017, and it’s sought to be the biggest player in Democratic digital politics: in November, she announced plans to drop $75 million in anti-Trump ads ahead of the 2020 election.

ACRONYM and a constellation of affiliated organizations—political action committee PACRONYM, consulting firm Lockwood Strategy, and a network of ostensibly independent digital news outlets—have skyrocketed to the heights of Democratic digital politics since its founding. They’ve courted huge investment from big names in Silicon Valley. And they’ve been heralded as the antidote to perceived Republican digital dominance since the 2016 presidential campaign.

But in trying to take on such a wide swath of digital political roles, ACRONYM has also been drawn into roles that appear to be in conflict: not just political vendor and vote tabulator, but also ostensibly-independent media mogul and Democratic activist.

Such conflicts have been apparent in ACRONYM’s backing of a handful of state-specific media organs billed as editorially-independent journalistic outfits. Through investment in an entity called Courier Newsroom, McGowan’s group has seeded such outlets in the key swing states of Wisconsin, Virginia, Arizona, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and North Carolina. The left-leaning consulting firm Lockwood Strategy, in turn, has helped staff up the outlets, and in at least one case, Lockwood was on the payroll of the Virginia Democratic Partyas an ACRONYM-backed outlet favorably covered the party’s 2019 statehouse candidates.

In other words, one McGowan company was drawing a paycheck from the party as another pumped out news content boosting its election prospects.

More recently, Lockwood and ACRONYM teamed up with a Democratic dark money group called House Majority Forward to test Democratic messaging in ten competitive House races, according to documents posted on an obscure “research” section of HMF’s website. The test campaign gauged voters’ responses to digital and direct mail ads hitting key issues such as drug prices and Washington corruption.

That test campaign ran from late November to early December. Shortly thereafter, Courier began running Facebook ads backing the Democrats in many of those same House races, including Reps. Elissa Slotkin, Lauren Underwood, Gil Cisneros, Antonio Delgado, and Tom Malinowski. And those ads mirrored the messages that ACRONYM and HMF had been testing.

Creative digital strategies such as its news ventures have earned ACRONYM a fair amount of coverage, much of it flattering. But others in the Democratic digital space say the attention the group has received is overblown or unwarranted.

One top Democratic operative noted that ACRONYM had publicly reported that they were going to launch $1 million of impeachment-related ads. But as of January 29, Advertising Analytics had shown them spending just $186,000, with their affiliate PACronym having spent $38,000.

Party officials were left even more incredulous and perplexed by Shadow’s work. The company had scored the contract to build the app just months ago and for a scant sum of $60,000. And there was no indication that it had the institutional capacity to handle the job. One Democratic official, who worked on the effort to rebuild the Obamacare website after it famously failed upon launch, recalled feeling queasy reading about those plans when they were announced. A successful operation would have required Shadow to have done a dry run during a previous election cycle or, at least, mock caucus to account for and mitigate against human error.

“I remember seeing them say we decided to do an app and thinking, ‘wow that is a terrible idea,’” the operative said.

The Nevada Democratic Party had been slated to use the Shadow app for its own caucuses on February 22. By midday Tuesday, the party put out a statement saying it would not be using the same app or vendor.