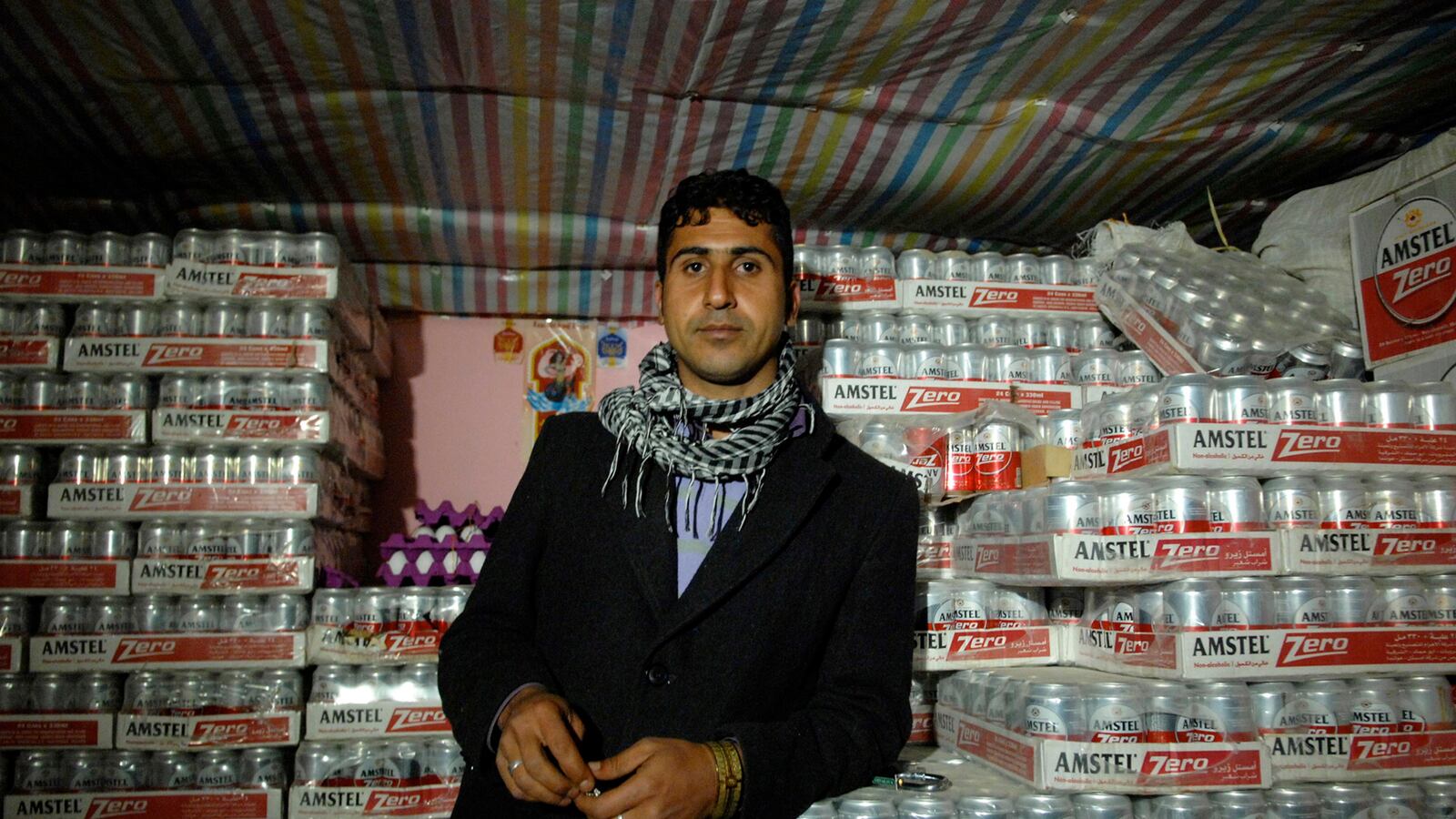

Islam forbids the drinking of alcohol and the Islamic Republic of Iran has very tough laws against buying, selling and consuming it. Very tough. According to Article 265 of the new Islamic Penal Code adopted in 2013, drinking alcohol is punishable by 80 lashes, regardless of whether the offender is a man or a woman. Yet the threat of such cruel penalties has not managed to reduce the popularity of drinking alcohol, particularly among young people, or its dramatic abuse by a stunning number of alcoholics.

Indeed, Iran has one of the most serious alcohol problems in the world. Although it ranks number 166 in alcohol consumption per capita, if you look at the World Health Organization estimates for people who drink 35 liters or more alcohol over the course of a year, the country comes in at 19th in the world. In other words, the number of alcoholics per capita puts Iran ahead of Russia (ranked 30), Germany (83), Britain (95), the United States (104) and Saudi Arabia (184).

The Islamic Republic is for the most part in denial. The government refuses to acknowledge or address the problem. (According to official statistics, nobody drinks alcohol in Iran.) Although alcoholism has been a problem in Iran for decades, the Ministry of Health only recently granted a permit to a clinic that deals with alcohol-related issues. It will only be open one day a week and will not employ qualified nurses or physicians.

Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) has operated in Tehran for a number of years. One former alcoholic, Alireza, regularly attends AA meetings. He has been “clean” for six years, he says, but like many alcoholics he’s taking things one day at a time. “Things that make other people happy—money, fame, a job and what have you—cannot satisfy an alcoholic,” he says.

According to Alireza, detoxification is a long process, lasting about three weeks. But even in the private sector there are still very few centers aimed at helping alcoholics give up drinking.

“If you are lucky and are friends with a caring doctor, he can come to your home and attend to you,” says Alireza. “Otherwise you have to go through the whole three weeks by yourself and without any help. There are many camps and clinics for drug detox, but there are none for quitting alcohol.”

Alireza says that he knows of at least three people who have died trying to kick their addiction.

A specialist at Tehran’s Bahman Hospital is only too well aware of the risks. “Unfortunately, everything in Iran has become ideological,” he tells IranWire. This includes medical protocols. When a person suffering from alcohol addiction stops drinking, “there is a high probability of seizures and heart failure, especially for those who have been alcoholics for a long time,” he says. Side effects can include severe depression and hallucinations. All these symptoms can be treated and controlled with medical care, but that’s just not available to most of Iran’s alcoholics. “If there is any good judgment remaining in this country,” says the doctor, “then it should be used to set up thousands of clinics to cater to those who want to give up alcohol.”

Former alcoholic Alireza says the new Health Ministry center is not much of a practical step forward, but its mere existence breaks taboos. It’s possible, he says, that some authorities are emerging from their state of denial and acknowledging “the old policies do not work.”

Because alcohol is illegal, it’s also extremely expensive. It takes a lot of money to buy a bottle of smuggled-in whiskey, so many people resort to drinking home-distilled alcohol or ethanol. “Such a clandestine and pathological way of drinking increases the chances of becoming an alcoholic exponentially,” says Alireza.

Even with hints that attitudes are changing, it’s still hard to imagine that people seeking a cure would be allowed to check into clinics and hospitals in Iran without getting into some sort of legal trouble, risking social stigmatization at a minimum, and possibly 80 lashes.

So, the trend of uncontrolled, dangerous alcohol consumption is likely to continue. Those wishing—or needing—to give it up will be forced to do so on their own, without the support of formal medical care. And in many cases, they’ll be risking their lives in the process.

This article is adapted from one written by Marjan Namazi for IranWire.