America faces an array of growing airborne military threats, from rockets fired at U.S. troops in Iraq to concerns that China is rapidly developing “aircraft carrier-killer” missiles. America’s chief of naval operations, Admiral Mike Gilday, warned last month that there was no time to waste in putting new technologies at sea within the next decade to keep up with threats.

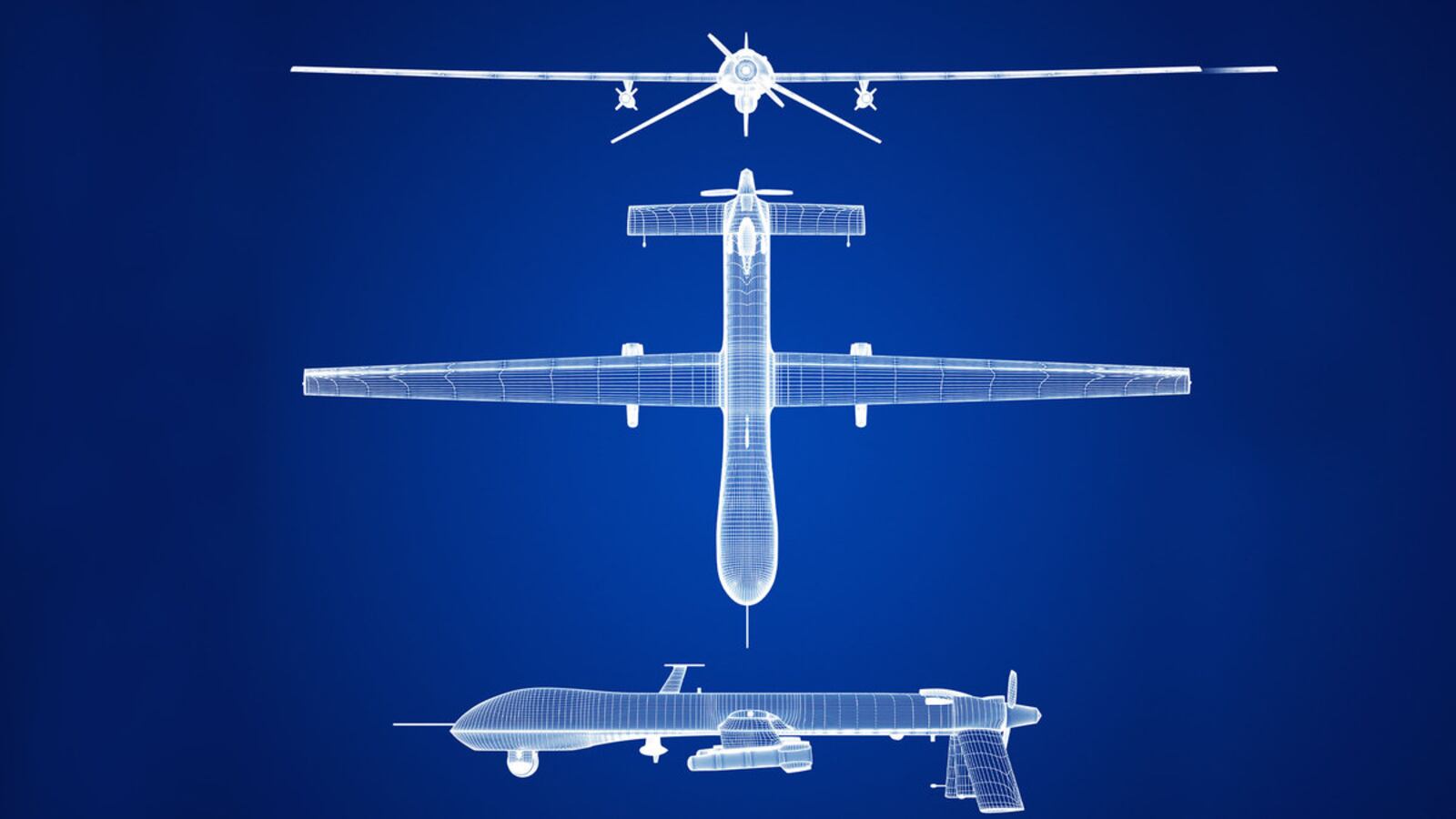

The nightmare scenario is already emerging. Iran used a drone swarm of 25 cruise missiles and drones to attack Saudi Arabia’s Abqaiq energy facility, temporarily disrupting half the kingdom’s oil output. Iran also downed a $220 million American Global Hawk surveillance drone in 2019. Tehran has been suffering tough sanctions from Washington and yet it is fielding unique technology that has major ramifications for the future battlefield. In short, the U.S. and other countries need better air defense to deal with threats at sea, in the air, and on land. The race is on globally for countries to build better radar, more precise missile interceptors, and drones and weapons that can evade these defenses.

Over the past year, The Daily Beast has spoken to experts in air defense and drone warfare from the U.S. to Israel, former drone pilots and engineers, and they all sound a similar alarm. "Today defense challenges are becoming versatile and require high operational capabilities and flexibility,” said Ron Tryfus, a vice-president a Israel Aerospace Industries Systems, Missile and Space Group.

Indeed, Israel has designed some of the most advanced air defense systems. Individual air defense systems cost hundreds of millions of dollars and global spending looks to explode in coming years. Washington has been supporting joint development of several systems, such as David’s Sling, with Israel, worth $500 million a year. India signed a $777 million deal for air defense systems from Israel’s IAI in 2018. Many countries are surprised at the cost of acquiring just a handful of systems. Poland was surprised to learn a 2017 deal for four U.S. Patriot systems would be $10 billion. Just the radar for the Iron Dome system costs millions, as Czech Republic found out when it spent $125 million on Israel’s Iron Dome radars made by Elta in 2019. It’s difficult to estimate overall spending for air defense globally, but these programs run into the tens of billions of dollars.

Across the sea in the U.S., a former UAV operator said drones are coming of age.

The shock of what it means to be left naked without defenses was revealed a year ago when Iran fired more than a dozen ballistic missiles, each 40 feet long with 1,600 lbs of explosives, at U.S. forces in Iraq. Iran was retaliating for the U.S. killing of Iranian general Qasem Soleimani. For the 110 troops injured in the attack it was a lasting trauma. The massive missiles came in over an hour in several volleys. There were no defenses to stop them. Now the U.S. is seeking to remedy this across the board to stop drones, mortars, rockets, and giant missiles.

Just after the New Year, Israel announced that it had delivered a second Iron Dome battery to the U.S. Army. The deal had been in the works for years and the first batch of the advanced Israeli air defense system had been sent to the U.S. in the fall of 2020. The final plans for the Iron Dome in the U.S. is not clear, a large country like America with sprawling bases all over the world would need dozens of these systems to integrate as air defense. The final concept will be to see how Iron Dome works and how a version of it might be practical for U.S. forces, perhaps as a mobile version on bases in sensitive places.

The Israeli system, which is now being built with Raytheon in the U.S., is about to celebrate its 10-year anniversary of first downing a rocket fired from Gaza in 2011. Weapon systems don’t usually get garlanded like people, but for Iron Dome, the anniversary is especially poignant. It is a symbol of how air defense systems have become increasingly important. This is especially true in an era with new drone swarms and missiles that maneuver toward their target, making them hard to intercept.

Around the world countries are investing in better air defense systems and the sensors that go along with them, such as better radar to detect incoming threats. This investment might not have been obvious several decades ago when the Cold War ended and large conventional militaries appeared ready to be moth-balled. Twenty years of the U.S. waging a global war on terror saw the U.S. military invest in armed drones, better surveillance and special forces. While that is one trend globally, the U.S. military is increasingly looking to how to come to terms with a rising China and more assertive Russia.

The Middle East is where new air defense systems have often been tested. The Patriot missile system was deployed during the Gulf War 30 years ago and used to confront Iraq’s Scud missiles. However, the system was criticized for failing to engage many targets. At the same time Israel and the U.S. began to work on the Arrow system, initially designed to counter short-range ballistic missiles. Billions was spent on the program and the U.S. and Israel also co-developed the David’s Sling system, which was envisioned as a unique missile interceptor to counter rockets and cruise missiles, which maneuver and are slow. These systems were developed in the 1990s and 2000s and are now operational. Alongside Iron Dome they form Israel’s multi-layered missile defense shield. Iron Dome has been most effective, intercepting around 1,000 projectiles by 2014. David’s Sling and Arrow have also been used in drills and several times in combat.

To understand how important air defense is today, it is worth looking beyond Israel and the U.S. to recent developments in Russia, Turkey, the Persian Gulf, and India. Russia has a plethora of air defense systems, some designed to counter short-range threats like helicopters, and others like the S-400 for long-range threats. Russia’s S-400 has become a symbol of its strategic military diplomacy, using the system to engage with countries that were once close to the U.S. For instance Turkey, a member of NATO, purchased the S-400 and is now under U.S. sanctions because of its choice. India has considered the system and Russia has dangled it, or other versions of Russian air defense, in front of Egypt, Saudi Arabia and Iraq. Serbia has also acquired Russia’s Pantsir air defense systems.

In India, Israel Aerospace Industries and several high-profile Indian companies are building a medium-range surface-to-air missile system called MRSAM. The multi-billion-dollar program will see this system deployed with ground forces. India has also acquired it for the navy. Like other air defense systems these days it is supposed to be able to shoot down planes, helicopters, drones, and missiles.

U.S. forces since May 2019 have found themselves under attack by pro-Iranian militias firing rockets at bases where U.S. personnel are located. A U.S. contractor was killed in December 2019 and three members of the U.S.-led anti-ISIS coalition were killed in March 2020. This was part of growing tensions with Iran that have taken place during the Trump era. For military planners the best way to confront the rockets was to install a system called C-RAM at the U.S. embassy in Baghdad. It’s not every day U.S. embassies get their own air defense. Last year marked a turning point in this regard. C-RAM is supposed to be able to shoot down rockets, artillery and mortars. Like other short-range systems it can defend a small area of several miles, but you’d need numerous weapons like this to defend bases across Iraq. The U.S. has now withdrawn from a half-dozen of the bases it was using in Iraq.

It is also worthwhile looking at several recent incidents. In Azerbaijan—as The Daily Beast reported—the armed forces acquired large numbers of drones and used them to target Armenian forces. The drones, some of them from Israel and Turkey, hunted down Armenian air defense and destroyed radar and vehicles. They also hit Armenian tanks and artillery, helping Azerbaijan win a border conflict. Reports in the U.K. say that Britain now wants more armed drones after seeing that success.

In September 2019, Saudi Arabia awoke to a shock after Iranian drones and cruise missiles struck its Abqaiq facility. The drones and cruise missiles avoided air defense at Abqaiq, flying low and approaching from a side that radar did not cover to cause havoc. This type of attack, sometimes called a “drone swarm,” is meant to either get around defenses or overwhelm a system. Air defense systems usually use missiles, or sometimes even guns, lasers, and jammers, to take out threats. But the systems don’t have an endless supply of missiles. If you launch enough drones at them, or hit their radar, they are effectively blinded.

Most militaries are still unprotected in this new era. For instance, when the Iraqi army stormed into Mosul in 2016, it had no defenses against ISIS’ home-made drones. U.S. drones have been so successful against terror groups from Pakistan to Somalia precisely because the insurgents had no air defenses against them. But that battlefield is changing now. The U.S. is no longer the world’s sole drone superpower and the U.S. is also learning from Israel how to deploy multi-layered air defense. At the same time, Iran has been testing new drones. At a drill in early January, Iran showed off new kamikaze drones and drones that can launch missiles. It has supplied drone know-how to allies like the Houthi rebels in Yemen, and also to Hezbollah and others. It is unclear if Iran’s adversaries have the right technology to confront Tehran’s new drones. It appears that almost every day brings new types of these complex threats. Even the Taliban in Afghanistan are using drones. The Afghan army, despite billions in funding over the years, doesn’t seem to have a way to stop them.

The arms race to confront new aerial threats has been going on for years. During the Cold War it involved systems like the Russian SAM and U.S. Hawk missiles. Today’s arms race is different because of the multiplicity of threats. I’ve seen this race up close covering wars from Gaza to Ukraine and Iraq. Prior to Iron Dome rockets fired from Hamas militants in Gaza would land in southern Israel and the only thing people could do is run for cover when air raid sirens sounded. In Ukraine, I sat in trenches and we listened for drones piloted by Donbas separatists overflying the Ukrainian positions. Even ISIS terrorized its adversaries with drones, and the Taliban is using them too.

In mid-December, Israel launched a major air defense drill, combining the U.S.-backed Arrow, David’s Sling and Iron Dome systems. These were designed to confront different layers of threats, so that the Arrow might shoot down a large ballistic missile, while Iron Dome goes after short range missiles. The systems have been improved to stop drones, cruise missiles and maneuvering weapons. What that means is that a system designed to calculate the trajectory of a rocket and intercept it, now can hunt down a drone that might be flying low and hiding in canyons and wadis.

The implications of countries acquiring air defense are not only financial and technological. The systems cost billions of dollars and are a major investment. They also take years to procure. The U.S. army for instance has been looking at Iron Dome since at least 2017. Turkey acquired the S-400 in 2017 but has only barely made it operational. Procurement is slow and the systems take years to make. The technology and the threats change more rapidly than the systems. It took the U.S. almost a year to deploy C-RAM in Baghdad, despite threats from rockets.

Israel believes that its multi-layered air defense system enabled it to postpone conflicts in Gaza. Israel went to war with Hamas, launching a ground invasion of the Gaza Strip in 2009 and 2014, and a shorter clash in 2012, partly because of increased rocket fire. However in 2018 and 2019 there were nearly 1,500 rockets fired at Israel from Gaza and Israel intercepted most of them, reducing the push for a wider war. The calculations that countries need to consider in their investments in air defense is whether the systems will also enable commanders and political leaders to make more pragmatic choices, rather than have to move quickly as cities are under fire from rockets. On the other side of the coin they have to consider rapid investment in new systems because of game-changing threats, such as China’s “aircraft carrier killer” DF-21 missile.

Countries that are investing in air defense tend to be purchasing and developing only aspects of an integrated system. Many countries have aging air defense from the Cold War era and are only modernizing pieces of their forces. That may be economical for countries that are not facing a conflict in the near future. However as recent conflicts in Libya, Yemen, Azerbaijan, Syria and tensions between India and China illustrate, there is an immediate need to modernize air defenses.

Russia has been successful selling its S-400s but it is Israel that has come to the fore. Jerusalem has managed to transform decades of experience in dealing with multilayered aerial threats into a booming global industry that shows no sign of slowing down.