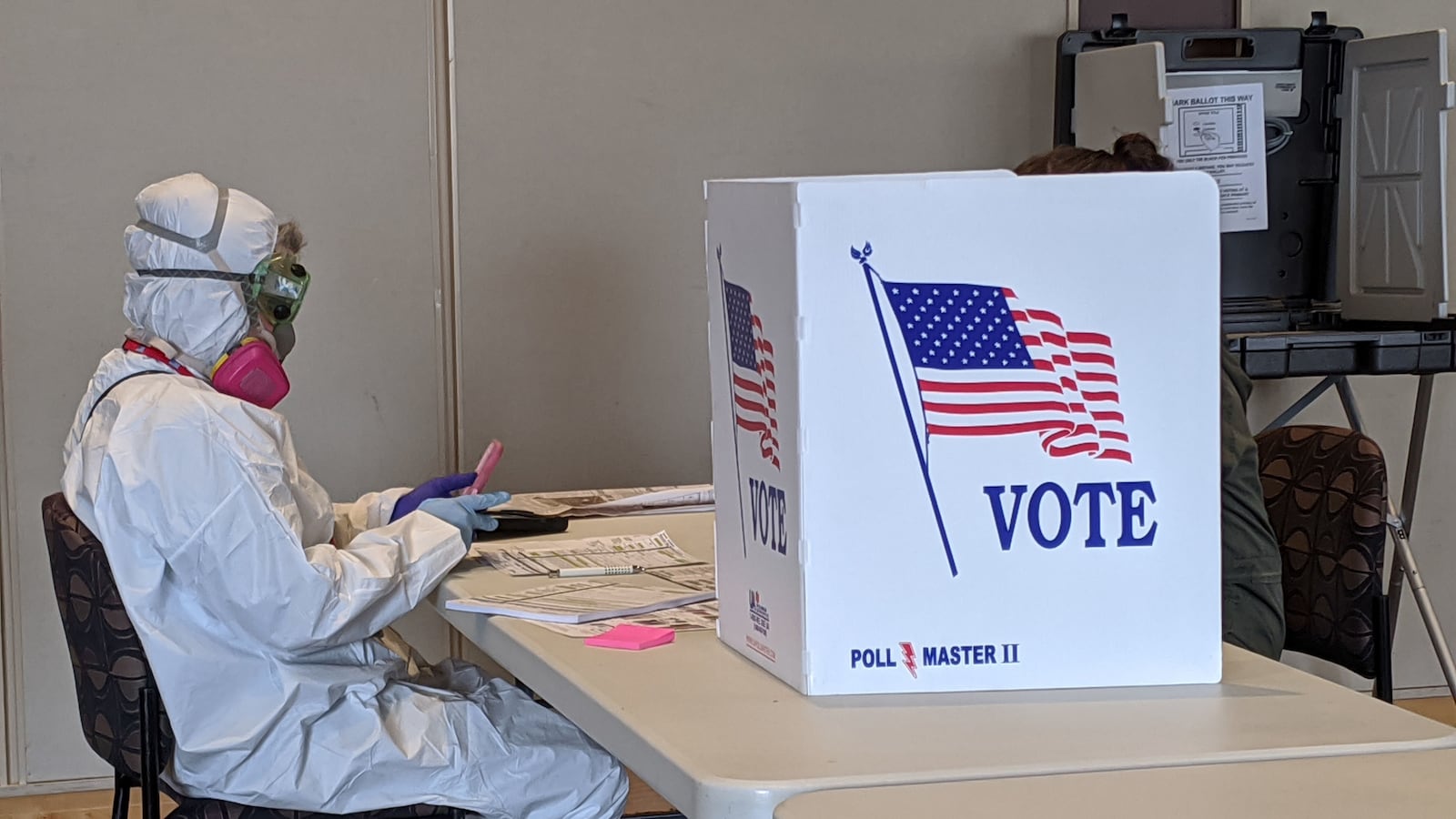

The fear in Wisconsin was clear.

The coronavirus pandemic was still relatively new in early April as the Wisconsin governor's late attempt to delay the fast-approaching primary election was thwarted by a GOP court challenge. And even with a crucial state supreme court seat on the line, along with the presidential primary, some Democrats worried that asking people to head to the polls on election day could be a major health risk.

Four months later, as other states have also taken a similar blended election approach with an emphasis on mail-in voting along with in-person options, those concerns may have not been as far-reaching as some had first feared. But as the country hurtles towards holding a contentious presidential election during the pandemic, both health and voting rights experts remain alarmed as political battles rage over elections during the pandemic.

“We were lucky in April here, I don't know if we would be that lucky again,” said Malia Jones, an associate scientist in health geography for the applied population laboratory at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

In early April, there was "very little disease circulating," in the state, Jones said, noting that voting by mail “is clearly the safer option.”

There doesn’t appear at the moment to be a definitive sign that in-person voting on the day of Wisconsin’s April 7 contest became the kind of cataclysmic super-spreading event that would have been a nightmare scenario for many in the state. But in the months since, as primaries have wavered between the messy June 9 contest in Georgia and those running more smoothly like Kentucky’s June 23 primary election, the tension between public health and voting remains a complex one where clarity on the true health impact of heading to the polls in person on a given election day can remain in question.

A spokesperson for Wisconsin’s Department of Health Services said in an email to The Daily Beast that “71 people who tested COVID-19 positive after April 9 reported that they voted in person or worked the polls on election day,” but also noted that some of those positive cases “reported other possible exposures as well.” And an official for Kentucky’s Cabinet for Health and Family Services said the state was “unaware of any coronavirus cases linked to voting in the primary.”

In Georgia, which became a health policy battleground following the Republican governor’s fast push to reopen, the state’s public health department said in an email it “cannot definitively link cases to the primary elections” because “there is widespread community transmission throughout the state as well as businesses reopening and people generally more out and about.”

That’s part of the reason why Lawrence Gostin, director of the O’Neill Institute for National and Global Health Law at Georgetown University, remains “very concerned” about in-person voting during the pandemic. What the states are saying is “not reassuring at all,” he said pointing to the concept that “if you don’t look for cases, you’re not going to find them.”

“There's very little doubt in my mind that the only way you can do this safely is by postal ballot and by spreading out the vote to allow a lot of early voting," Gostin said. “But if you just have on election day people lining up to try to vote, it's going to be a disastrous period for the United States, both healthwise and for our democracy.”

When there's “really high” community spread of the coronavirus, it amounts to being nearly impossible to figure out where it's coming from, said Travis Glenn, a professor of environmental health science at the University of Georgia.

“If the level of spread is really high, how can you tell if a poll worker got it from sitting at the poll on Tuesday and not at the grocery store Monday night?” Glenn said.

But when it comes to individual voters the risks are “sort of low to modest” Glenn said, adding that it depends on the specific circumstances.

“I wouldn't expect for most people that this will be significantly more risky than shopping,” he said.

The safety and ability of holding elections during the coronavirus pandemic has become a tense topic across the country, as President Donald Trump has waged a war of words against mail in voting during the pandemic. At the same time however, voting by mail has helped ensure that states are still able to hold necessary elections even as the virus continues to spread, though issues with mail in ballots unrelated to fraud have on occasion led to lengthy wait times for results, like in New York’s June 23 primary.

In person voting is still a key part of the electoral process however as Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden made clear on Twitter amid the president’s scattershot attacks on voting by mail.

“Every American should be able to safely make their voice heard this November,” Biden tweeted. “We need to: - Expand vote-by-mail and early voting - Implement online voter registration - Make it safe and easy to vote in-person.”

Trump, who conceded support for mail in ballots in the must-win state of Florida, has been more blunt. During a recent appearance via telephone on Fox & Friends, Trump said: “We have people that really want to get out and vote. It's going to be very safe. But by Nov. 3, time-wise that's eternity, frankly, as far as I'm concerned.”

States need to be making vote by mail an option for everyone, said Sean Morales-Doyle, deputy director of the voting rights and elections program at the Brennan Center for Justice, but the reality remains that in-person voting is going to happen in November because "we are not capable as a nation of turning to an all-mail system," by then.

The risk can’t be eliminated, Morales-Doyle said, though elections officials implementing robust protection measures helps. But they must also figure out ways to reduce the amount of people that can crowd a polling place and hurt social distancing efforts, he said, including by expanding early voting, having polling places that allow for social distancing and encouraging vote by mail.

“We think if elections officials do all of those things that there is a way for in person voting to happen with a reduced risk,” he said.

A roundup of studies by Wisconsin Public Radio in May showed there were different findings about the public health impact of the Wisconsin primary, though a recent report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention focusing on Milwaukee had a more favorable view.

“No clear increase in cases, hospitalizations, or deaths was observed after the election, suggesting possible benefit of the mitigation strategies, which limited in-person voting and aimed to ensure safety of the polling sites open on election day,” the report said. “Epidemiologic trends were likely also influenced by a relatively lower turnout of voters overall compared to spring 2016.”

Even with more widespread voting options the potential for issues remain, with a clear example being Georgia’s delayed election that was held on June 9. To Nsé Ufot, CEO of the New Georgia Project, the day was one that saw “extraordinary long lines,” a lack of familiarity with machines by both election workers and voters and confusion with the vote by mail process.

Looking ahead, safety concerns haven’t been far from Ufot’s mind.

“From what we've seen in Georgia, what we're seeing in other states, there are still measures that county election officials and our secretary of state can take to preserve a safe in person voting option, and we just don't see that they've gone all the way yet,” Ufot said.

And back in Wisconsin, the fears that were present leading up to the primary election haven’t subsided for some ahead of November. On Wisconsin’s April election day, Price County Democratic Party chairman Steve Gustafson told The Daily Beast he was worried about the virus spreading because of in-person voting, pointing to concerns that people are “going to spread the virus and people are going to die. And that's not right.”

Asked again about his fear’s as November fast approaches, the county Democratic chair was once again blunt.

“I don’t think anything has changed since then,” he said.