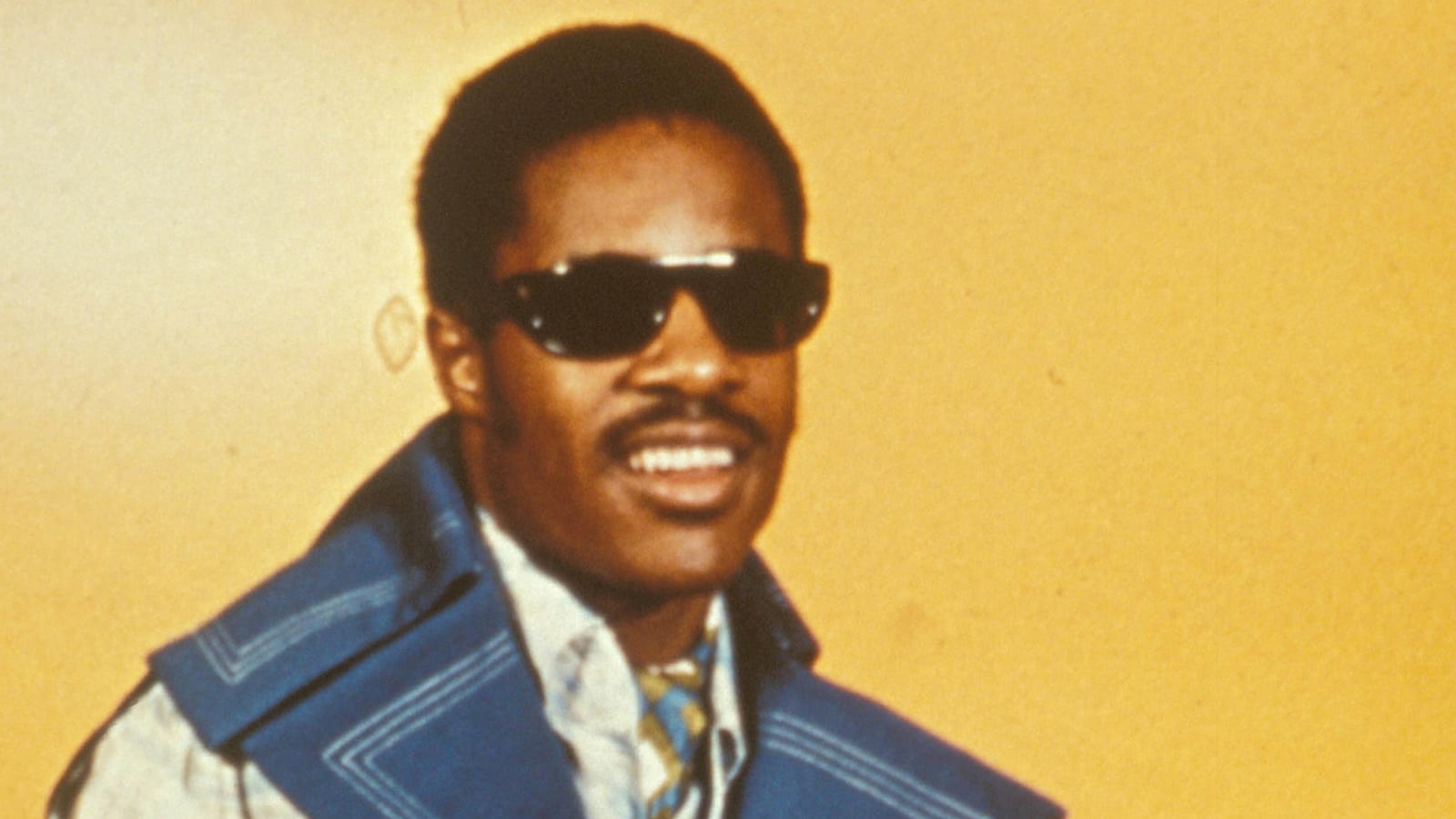

Stevie Wonder is robbing a widow, according to said widow.

Susan Strack has hauled the superstar to a Nevada federal court to recoup $7 million cash, “plus interest,” that she says is hers because of a contractual agreement between Wonder and her late husband Johanan Vigoda to pay 6 percent of Wonder’s royalties to Vigoda’s heirs forever.

Vigoda, who died in 2011 after a battle with pancreatic cancer, was a colorful character. According to his friend and fellow lawyer Bob Lefsetz, Vigoda enjoyed “exotic diets” and wandering around Venice Beach, dressed like a homeless person. He played a judge handing down a stiff sentence in Wonder’s extended version of the hit track “Living For The City” and according to one obituary he secured Wonder’s new contract while “standing on his head, doing yoga.”

Vigoda had been Wonder’s lawyer for over 40 years. He had famously freed Wonder from his terrible 1960s Motown contract, which was described by Strack’s lawyers as “oppressive,” and secured him a new one that was “among the most lucrative in the music industry.”

Under that new contract, the royalties alone on any of Wonder’s hits are worth millions, and the late lawyer had his client execute documents ensuring that Vigoda and his heirs would receive of 6 percent (1 percent above the industry standard) in perpetuity.

But now Wonder (referred to by his real name as Stevland Morris in court papers) claims he was misled. The contention is that either the clauses were intentionally shielded from Wonder or that the singer, who has been blind since birth, couldn’t catch the generous portion of his royalties that would go to Vigoda and kin in perpetuity when the paperwork was read to him.

A source close to the legendary singer and songwriter told The Daily Beast that if the terms established by Vigoda to give royalties to him and his heirs forever were ever read to anyone or spelled out, somebody would have brought it to Wonder’s attention before he dipped his fingers in ink to sign.

“If we ever heard anything like this somebody would have spoken up, and said ‘Stevie, let’s go over here and talk about this,’” the source said. “It’s amazing that that language had been repeated over those years and I just can’t even imagine anybody seeing that and not saying something about it.”

“There would have been comments made,” the source said. “It’s beyond my comprehension that these details were even introduced.”

The documents were executed from 1971 up until 1992 by Wonder affixing his inked fingerprint as his signature, with witnesses (who varied from his wife to friends) by his side. Of course, it is possible that the witnesses could have overlooked or failed to catch something fishy.

“Unless they’re either an attorney or well-versed in the music profession I would say it’s very difficult for them to understand that [language],” said Kevin J. Greene, a professor who teaches entertainment law at Thomas Jefferson Law School in San Diego. “As a layperson, they could read that provision and not necessarily understand what is going on.”

Greene said Stevie Wonder’s music catalogue is “worth a fortune” and to siphon a sizeable percentage to Vigoda’s heirs in perpetuity is “quite unusual,” he added.

“That’s more like a share of the copyright and that’s something that any court is going to look at with a lot of suspicion unless it was properly witnessed by a legal professional,” Greene said.

Greene, who recently repped funk icon George Clinton in his bid to reclaim his copyrights, pointed out that Vigoda’s terms may be extreme, even as far as music contracts go.

“That’s a phenomenal sum of money,” he said, adding that the backend payout in perpetuity pushes the standard practice. “To take that kind of percentage out of the copyright is definitely excessive.”

There are parameters in California, for instance, where lawyers must not overstep when it comes to compensation. Overcharging or setting up self-serving deals that may hinder the client are defined as “unconscionable.”

However, Chicago-based entertainment lawyer Peter J. Strand says “the part that the client continues to pay post-death as long as the client continues to receive royalties is not unique. I don’t know that I’ve seen a fee arrangement where the lawyer’s heirs continue to collect. But in my experience it’s not shocking; even with the heirs.”

Perhaps more worrisome, according to Strand, is that Wonder signed these contracts in what may be questionable circumstances. “You wonder how did they validly get him to sign and was it explained to him appropriately,” he said. “And if there was a witness (in Wonder’s case one of the witnesses was his ex-wife) if they have a stake in the deal.”

“But the way artists are, sometimes they will sign anything that’s in front of them—sighted or not,” Strand said.

Wonder’s lawyers contend that he would have “never agreed to such an arrangement” if he could see. They say that Vigoda may have been in dereliction of his duties both as a fiduciary and a lawyer by failing to “adequately explain the concept of heir,” not informing Wonder that he should retain an independent attorney “to review and advise him on the contract,” and luring Wonder to endorse terms that basically gave away the farm with Vigoda collecting “a percentage of royalties… forever, even after the attorney and the artist died,” which Wonder’s lawyers write in their counterclaim was “unfair and unprecedented.”

Even more important, Vigoda’s agreements with Wonder may be void because Vigoda could have been advising without a license when the papers were drawn up.

According to the counterclaim filed by Wonder’s attorneys, Vigoda “was never licensed as an attorney in California…” and “since Jan. 1, 1982 was never licensed as an attorney in any jurisdiction.”

The Daily Beast can confirm that indeed Vigoda was not licensed to practice law in the Golden State, where it appears the majority of Stevie Wonder’s retainer contracts were executed. He would have been forced to take the California State Bar exam to be a lawyer in L.A., state officials confirmed.

While we found that Vigoda passed the New York State bar back in 1953, it’s unclear if he was permitted to practice in Nevada where his wife still resides.

The Daily Beast’s numerous phone calls and emails to reach attorneys representing both Strack and Stevie Wonder were not immediately returned.

According to his own declaration document filed on April 16, 2015, Wonder believes any dealings with his attorney carried an expiration date. “I met Vigoda in New York and I executed my original agreement with Vigoda (where I agreed to pay him 6 percent of my income over a certain period of time),” Wonder wrote and signed with his fingerprints.

After her husband’s death, the widow Strack allegedly sealed her financial fate by going stealth and keeping out of touch, even “avoiding [Wonder’s] telephone calls.” The court papers suggest that she went to a probate court to make the royalties agreement bulletproof when she “secretly applied for and received an order… that she was entitled to the 6 percent that had previously been paid to Vigoda.”

Armed with the order, she then solicited music companies that paid Stevie Wonder his royalties and “directed that they pay her 6 percent,” according to the counterclaim filed by Wonder’s attorneys. In the counterclaim Strack “did this in secret, without telling [Wonder].”

Only after discovering the subterfuge in 2013 did Stevie Wonder call the record companies to get them “to stop paying Strack.”

Since then, the lawsuits and counter-lawsuits have been flying. “With each passing day, [Stevie Wonder and his companies] line their pockets with Ms. Strack’s money,” says Strack’s amended complaint.

According to her complaint, her husband, heralded in his prime as “one of the most effective attorneys in the music industry,” essentially gave Wonder his own money printing machine.

Vigoda’s longtime friend and fellow music industry lawyer Bob Lefsetz described Wonder’s lawyer as a brilliant mind and loyal to the end. “He was a phenomenal entertainment business lawyer who did great work for Stevie Wonder,” Lefsetz said, noting that Wonder wasn’t his pal’s only notable client.

In terms of the legal imbroglio between his buddy’s widow and Wonder, Lefsetz is in the dark. “I know Johanan started working for him in the 1970s and I know that many music business attorneys are on percentage deals,” he said. “But this is a complicated case with a blind man and probably ancient contracts.”

“Johanan Vigoda was someone I knew and he was someone who had an excellent reputation as an excellent lawyer,” Lefsetz said. “He was a very smart man. And legend has it he did very good work for Stevie Wonder. But I can’t speak for the dead.”