I wasn’t expecting any other moviegoing experience this year to top my rambunctious screening of Don’t Worry Darling on opening day. Then I saw the premiere of Is That Black Enough for You?!?, a new Netflix documentary analyzing the legacy of 1970s Black cinema, at last month’s New York Film Festival. Based on the crowd’s sporadic cheers and applause–as well as one man on my left who was literally on the edge of his seat—you’d think we were watching a sporting event and not a 135-minute nonfiction film about Hollywood racism.

That reaction was entirely appropriate, considering one of Is That Black Enough for You?!?’s main arguments: not only does representation for Black people in film matter, it’s also exhilarating.

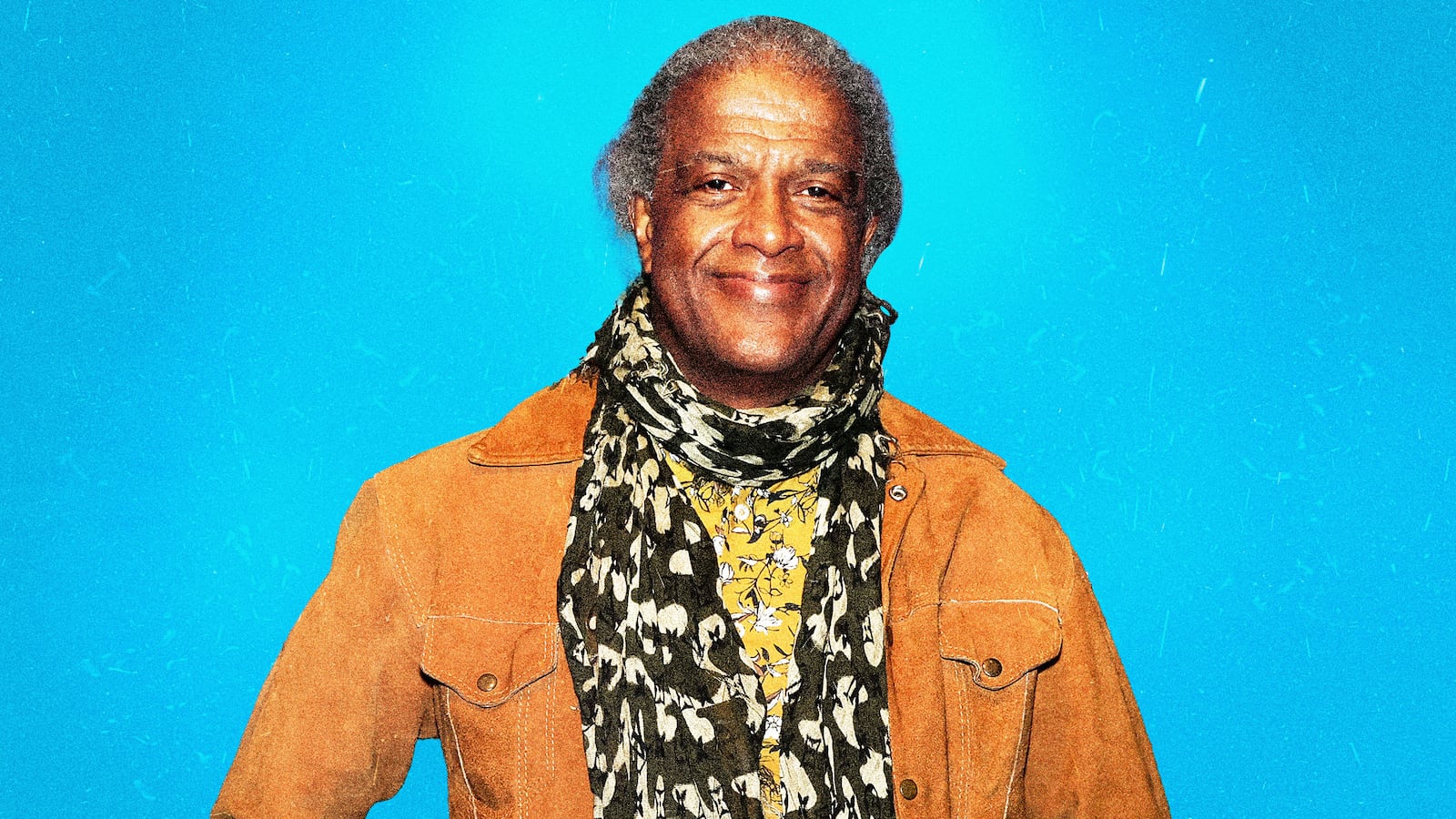

When I brought up the audience’s response to Elvis Mitchell, the documentary’s director and writer, over Zoom, he was pleasantly stunned. (I incorrectly assumed he sat in the audience after he introduced the film at the NYFF screening.) Yet it’s Mitchell’s infectious enthusiasm and fiery voice as a narrator that makes Is That Black Enough for You?!? , now streaming on Netflix, so effective and cathartic.

Produced by David Fincher and Steven Soderbergh, the documentary is a sprawling overview of a thrilling and influential decade of Black cinema that’s often inaccurately reduced to the label “Blaxploitation” by film scholars, cinephiles, and art institutions—that is, when it’s not being wholly ignored. When discussing the impetus for making Is That Black Enough for You?!? at the premiere’s Q&A, Mitchell referenced Peter Biskind’s seminal 1998 work Raging Bulls, Easy Riders: How the Sex-Drugs-and-Rock ’N Roll Generation Saved Hollywood about the same time period and how it glosses over the contributions of Black filmmakers. Likewise, a good portion of his film explains just how impactful movies like Shaft, Super Fly, and Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song were to that time period, from marketing to costuming to opening credit sequences.

Micthell’s keen perspective as a film connoisseur and a Black man, whose identity has historically been degraded by the medium, guides the documentary, forming a rigorous analysis of cinematic history and a personal love letter to Black artists. While the film creates a timeline from classic Hollywood to the 1978 financial failure The Wiz, the movie occasionally abandons this chronological structure to focus on certain critical junctures, like the silent film work of Oscar Micheaux, or William Greaves’ 1968 experimental film Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One. Additionally, the film features some incisive, funny, and brutally honest commentary from Whoopi Goldberg, Samuel L. Jackson, Charles Burnett, Mario Van Peebles, Zendaya, and Harry Belafonte, among other Black Hollywood figures.

The doc maintains an energetic, freewheeling energy, and in a recent conversation over Zoom, Mitchell is just as bursting with interesting nuggets and digressions about Black cinema and pop culture as he is throughout the film. The highly respected journalist and host of The Treatment spoke to The Daily Beast about his journey from film critic to filmmaker, a possible book adaptation, and whether Black cinema is becoming more acknowledged in a post-Black Lives Matter world.

At the Q&A after the NYFF screening, you said you had initially tried to pitch the idea for this documentary as a book and was turned down by publishers. After the critical success of the film, are you still interested in exploring the topic as a book?

If that were to become a possibility, yes. I would certainly respond to it. Put it this way—I wouldn’t miss any meals waiting for that to happen. To quote Austin Powers, that train has sailed, I think. And so I think that I got to make this, and that’s what I’m happiest about. Because I have mentioned this before, that the fun of doing it as a movie is that I get to use all the tools that this medium has to offer, which is to say, picking clips that are not the kinds of things we normally see—like, explaining what that chase sequence in Superfly meant and how it was staged and why that was important. It starts to beg the question of what would I do with a book? I guess I could talk about a lot of things I didn’t get a chance to.

For example, I leave this thread for anybody who knows: two of the biggest shows in the ’70s were inspired by movies [from] this period. Norman Lear and his producing partner Bud Yorkin saw Cotton Comes To Harlem, saw Red Fox dressed as an old junk dealer and said, “We just bought this British show that we’re trying to do an American version of called Steptoe and Son. So would you be interested in playing a junkman?” So that becomes Sanford and Son. And then Cooley High is turned into the show What’s Happening!!. So there’s so much stuff that I could have gotten into that I just didn’t get a chance to explicate. And if the book comes along, maybe I’ll just end up self-publishing it.

Did you find the filmmaking process easier or more difficult than you expected?

Well, it wasn’t easier [laughs]. But what I’ve learned about this–if you’re surrounded by great people, then they’ll note if anything is a problem. There were some issues. We had to get a certain license. A sequence we built together based on getting a certain clip or piece of music—and someone would go, “Oh no, you can have that” for whatever reason. And that, to me, became an enthralling part of the process. I said, “Oh, no wonder that people love post-production,” because you really see what the possibilities are. I was afraid that I wouldn’t be able to meet the challenge. But instead it was stimulating having a new set of instruments to use to solve problems with.

I’ve said before, there was one sequence. And I just thought, “Oh my god, we can’t do this.” And both Fincher and Soderbergh said, “That’s a movie moment. Why would you take that out?” And I said, “Oh, you guys do this kind of stuff on purpose.” It doesn’t just happen. You actually have deliberation in these ways. And that was wonderful.

How much research did you have to do for the film compared to what you already knew as a film scholar?

It’s funny because a lot of the things just came up in the course of my life and pieces I was going to write that I didn’t get to write for a publication. I’m a vinyl collector, so I was just constantly buying records. I collect posters, too. I had amassed what were, in fact, research materials. And I always have kept notebooks and journals and wrote thoughts and ideas I had. And when I was at dinner with Toni [Morrison], she just started talking about Pam Grier and grabbing napkins off other tables and writing things down. So this accretion of my interests just ended up being this hidden, inadvertent compiling of research.

You cover so many films in this doc and even touch on other points in pop culture before the ’70s. How did you know when you wanted to stop?

The time period makes it so much easier, ’68 to ’78. So just treating it kind of like a calendar gave me some place to go. The thing that I thought was hardest was trying to build a structure, as if there was a rise to a climax and then the down cycle as we start to realize that the studios really have no faith. They have no faith in anything other than Black action films. There was no real push for a movie such as Sparkle, which has one of those phenomenal Curtis Mayfield scores—again, five scores in 10 years. Who writes five scores in 10 years?

So, having this go to 1978 and to be able to end on hope—not only the hope, the optimism that I think a piece of art such as Killer of Sheep evokes, you think, this is itself a climax. This is one of the greatest moments in ’70s film. But I think it needed to end with going back to Sidney. And there were questions. How does Sidney Poitier figure into all of this? And I thought it wasn’t worth it if I couldn’t figure out something to offer about Sidney. Then I realized he gave it to me. And I could just use that, and that’s a way to end it.

Post-BLM, there’s been a push by streaming platforms and film libraries like The Criterion Channel, Netflix, and Hulu to spotlight Black movies, both contemporary and these older hidden gems you include in the documentary. Have you noticed an improvement in how these institutions engage with Black films, or do you still see a lack of curiosity?

I mean, I think places that really guide and influence people’s taste, places such as Criterion and Netflix—when these kinds of movies go up on Criterion, folks kind of go, “Oh, they must be important.” Because so often, people don’t know what “important” is. And Criterion giving them that that real seal of approval means something. But also offering them up on a platform such as Netflix that everybody goes to makes people say, “Oh, this is worth my time.” So these things are all important. I think as long as there’s access, I think that begets curiosity. And with curiosity, we move somebody to make the next movie or do the next thing.