Veteran financial journalist Luisa Kroll, who co-edits the Forbes 400 rankings of the richest people in the United States, has stopped taking calls from an especially unpleasant plutocrat.

“These people are used to getting their way—they don’t like being told no,” Kroll told The Daily Beast about the unnamed tycoon, one of a handful of wealthy folks who feel so bitterly underappreciated by Forbes that they have personally lobbied the magazine—Donald Trump prominent among them—for higher and occasionally fictitious valuations.

“Quite frankly, there was one billionaire who became so abusive that I now have one of my deputy editors dealing with that person,” Kroll said. “I’ve been screamed at—literally screamed at, like, spewing! You literally hold the phone away from your ear… That person believed to the bottom of his soul that his assets were worth more than we set.”

Once again this week, in a decades-old rite of autumn, the 102-year-old magazine will burnish—or bruise—hundreds of massive egos, indulge a collective impulse for financial voyeurism, and possibly even provoke a bit of class resentment by publishing its annual Forbes 400.

It will also reignite a timeworn debate concerning the accuracy or, more likely, inaccuracy of such rich lists, including the rival Bloomberg Billionaires Index, which has been ranking the planet’s wealthiest humans since 2012 and adjusts its valuations on a daily basis (minus former New York Mayor Mike Bloomberg—No. 10 on last year’s Forbes 400, with $51.8 billion—because of a quaint in-house policy that his eponymous financial services and media empire does not cover itself).

Forbes, meanwhile, has been compiling its own list of the world’s richest people—and publishing its international ranking of more than 2,000 billionaires every March—since 1987, a quarter-century before the appearance of the Bloomberg rankings.

Yet, when it comes to personal fortunes derived from privately held companies—such as Mike Bloomberg’s, Revlon billionaire Ronald Perelman’s, or, for that matter, President Trump’s—the numbers are notoriously difficult to determine. One indication of these difficulties is the significant disparity in valuations between several of the Forbes and Bloomberg rankings.

For instance, Forbes has Jacqueline Mars, of the candy empire, at $29.7 billion; Bloomberg puts her net worth at $43.8 billion. Forbes values Warner Music owner Len Blavatnik at $19 billion; Bloomberg, on the other hand, says $25.4 billion.

“It’s really purely guesswork and dick-measuring at its finest,” said a person who regularly deals with Forbes on behalf of super-rich clients (and asked not to further identified). “They will say, ‘We have research that shows this person gets this amount’—they estimate. They allow you to tweak it. They are wildly inaccurate. There’s no attribution. They never tell you where the client will be on the list.”

A second billionaire’s functionary—again, insisting on anonymity—is even blunter. “It’s a big fucking waste of time,” this person told The Daily Beast. “These guys don’t listen. They demand all this information that no one would ever give them and then, if they don’t get it, they just make it up. They’re impossible to deal with.”

Not surprisingly, the journalists who toil on the personal wealth beat—both at Forbes and at Bloomberg, where former Forbes journalists Peter Newcomb and Matthew G. Miller created Bloomberg’s wealth rankings before starting Daybreak, the company’s morning news service—argue that their methods are meticulous, as well as careful and conservative, and in many cases informed by decades of data on individual fortunes.

It’s not possible, however, to be exact, especially when the money is privately held, as opposed to invested in publicly traded companies, and thus not subject to Securities and Exchange Commission disclosure requirements. If the actual numbers are not forthcoming from the principals, then the list-makers use “comps” of publicly traded companies in the same or similar businesses to estimate values. Real estate, yachts, private planes, and art collections are also among the assets thrown into the mix.

“It’s an art, not a science,” said a person intimately familiar with the process. “A lot of it is precedent—it builds off the existing database and information over time. It’s the same people who have been working on it for years and they understand it. They do have tremendous skill and forensic ability.”

“If you were to say to any newsroom in the world, ‘Go find the 2,000 richest people on the planet,’ they would say it’s an impossible task,” Forbes wealth reporter Dan Alexander told The Daily Beast. “Forgive me for being immodest on behalf of my company, but I think the Forbes 400 and the world billionaires list comprise the most ambitious investigative business journalism project that exists.”

Yet, as Forbes itself has acknowledged, it’s quite conceivable for an especially creative and shameless billionaire to fool a gimlet-eyed wealth reporter. Trump, for one, managed to get away with inflating his net worth on the Forbes 400 list for decades, using his favorite lawyer, Roy Cohn, and his fictitious PR executive, John Barron (who was actually Trump on the phone), to lie and cheat his way onto the 1984 list, for instance.

In Timothy O’Brien’s 2005 biography TrumpNation: The Art of Being the Donald—which prompted the reality-television mogul to sue the author unsuccessfully for $5 billion after O’Brien reported Trump wasn’t even a billionaire but actually worth between $150 million and $250 million—O’Brien wrote:

“Donald and the Forbes 400 were mutually reinforcing. The more Donald’s verbal fortune rose, the more often he received prominent mentions in Forbes. The more often Forbes mentioned him, the more credible Donald’s claim to vast wealth became. The more credible his claim to vast wealth became, the easier it was for him to get on the Forbes 400—which became the standard that other media, and apparently some of the country’s biggest banks, used when judging Donald’s riches.”

As top Forbes editor Randall Lane reported in 2015, while the presidential campaign was getting underway, Trump personally orchestrated a long-running “epic fantasy” that the magazine sometimes enabled and more often did not. In 1990, after Forbes devalued Trump’s net worth to $500 million from $1.7 billion the year before, he got the Los Angeles Times Syndicate to publish his typically nasty ad hominem attack on publisher Malcolm Forbes, who had recently died at age 70, under the scurrilous headline “FORBES CARRIED OUT PERSONAL VENDETTA IN PRINT.”

Forbes’ current valuation of Trump is $3.1 billion—a figure based on his known real-estate holdings against publicly recorded bank loans. O’Brien, for one, argues that the figure is suspect because it’s unclear if the president has secret loan obligations. White House press secretary Stephanie Grisham didn’t respond to an email requesting the president’s current views concerning the Forbes 400.

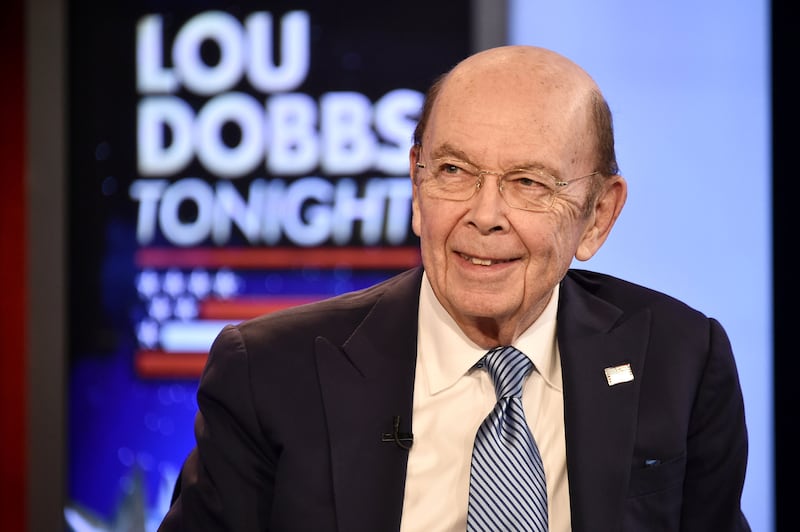

Also conspicuous among the flim-flam artists who have tried to hoodwink the magazine, and occasionally succeeded, are Trump’s secretary of commerce, Wilbur Ross—who personally fibbed to Forbes’ Dan Alexander about $2 billion in family trusts that never existed (in an October 2017 phone call that Alexander posted online)—and Saudi Arabian Prince Alwaleed Bin Talal.

As Forbes reported in 2013, the prince would temporarily pump up the share price of his Kingdom Holding investment company—only 5 percent of which was traded on the Saudi stock exchange, where Bin Talal could effectively manipulate the market—in the weeks before the publication of the world billionaires rankings.

“If someone is really determined to scam us, they can make a pretty good shot at it,” said a journalist on the wealth beat. “But the stories of those who have scammed in the past—those make people more hyper-aware, and I would say it’s gotten a lot harder. You don’t take many things at face value anymore.

“If someone comes to you and says, ‘Here are all the financials of my business,’ you don’t take it necessarily as a given, whereas 10 or 15 years ago people would, and that’s a mistake that has been made by lots of people in this industry. You learn from those mistakes. But if someone is still very, very determined, I’m not going to say we won’t make a mistake."

Forbes’ Randall Lane (a former Daily Beast colleague) said his reporters are ever-alert to bamboozling: “We go on the assumption that everybody’s either trying to spin us up or down.”

Indeed, some billionaires would rather not be listed at all for any number of reasons—not wishing to attract undue attention from the IRS, ex-spouses, or charity fundraisers, for instance. On the other hand, Los Angeles billionaire Nicolas Berggruen willingly cooperates with Forbes (which ranked him No. 1425 on the world list, with $1.6 billion, although he wasn’t rich enough to be included on the Forbes 400 as of 2017), because it enhances his profile as a philanthropist and think-tank founder.

“Nobody seems to be happy with where they actually are,” Lane added.

Oil refinery, real estate, and Gristedes supermarket mogul John Catsimatidis is a rare aggrieved billionaire willing to speak on the record. “I believe they’re undervaluing me substantially, but I’m not gonna argue with them, because who gives a shit?” said Catsimatidis, who was assessed at $3.1 billion and ranked No. 259 on last year’s Forbes 400 list (and No. 715 on the world list), but has been knocked down to $2.7 billion in Forbes’ running online tally.

“They had me at $3.1 billion for about four or five years now, and I’ve made a couple of billion since then,” Catsimatidis told The Daily Beast, claiming that he’s currently worth north of $5 billion. Notwithstanding that he gave Forbes an interview about his holdings for the 2018 rankings, he insisted, “I don’t deal with them. I let my people talk to them. But I understand that the San Francisco types do not like New Yorkers. I’ll just leave it at that”—a reference to Luisa Kroll’s San Francisco-based co-editor, Kerry A. Dolan.

“I have nothing against them. They got a job to do, let them do it… I don’t get spun up,” Catsimatidis said. “I don’t care. It’s just when certain people want to reflect the wrong stuff, you look at them and you say, ‘Eh. Bullshit.’”

Forbes’ Dolan responded: “The main reason Mr. Catsimatidis’ net worth has fallen is that values of publicly traded oil refineries dropped significantly in the past year; we use those as a guide to value his refinery. Forbes asked Mr. Catsimatidis and several people who work for him to provide documentation of his claimed additional assets and they declined to do so.”

A second well-known billionaire who asked not to be further identified said he instructs his team not to engage with the rich lists; he argued that the methodology of both the Forbes and Bloomberg rankings is vulnerable to embellishment.

The assessments are dodgy “except for reported wealth in official documents—SEC disclosures, etc., where if you’re an officer of a [publicly traded] company and you have great wealth, it’s down to the dollar, and all compensation is reported as well, so those are factual matters,” this billionaire told The Daily Beast. “But for most of the people on these lists, their primary wealth doesn’t come from being a corporately listed player.

“Therefore, the only way that Forbes can get its information is if the people cooperated. Trump is an exemplar. Most people, when they cooperate, put forward a greater figure than reality, because that’s what people do. I doubt people are sending their tax returns or the audited financial balance sheets of individuals. So it’s promotional. And out of that comes the question, why would anyone do it?

“Who would want to, other than for ego? It shows that these people are assertive, egocentric, and generally exaggerators. So it goes to character,” said this billionaire, who calls the entire process “unseemly.”

This week’s new rankings will be the 38th installment of the Forbes 400 since it was launched by the magazine’s media-savvy publisher Malcolm Forbes, who celebrated extravagance as a virtue and brazenly publicized his own lavish lifestyle of yachts, private jets, posh estates, hot-air balloon flights, and Fabergé eggs until his death in 1990.

He created his rich list as a promotional gimmick to compete with Time Inc.’s long-established Fortune 500 franchise.

“Malcolm wanted the Forbes 400 to be for personal wealth what the Fortune 500 was for corporate wealth,” said former Forbes journalist Jonathan Greenberg, who worked directly under the larger-than-life publisher on the very first rankings in 1982. “There actually was a Forbes 500 for corporations, which was very good, but when people would refer to it, they’d refer to it as the ‘Fortune 500’—which drove Malcolm crazy.”

At the time, Forbes was considered the No. 3 business mag after Fortune and Businessweek (which was acquired by Bloomberg LP in 2009 and rebranded Bloomberg Businessweek). Malcolm Forbes saw the Forbes 400 as a way to shake up the status quo.

“I think what drove it was celebrity culture, especially in the ’80s, but it continues to this day,” Greenberg recalled. “The concept of business people being celebrities was something that was very unknown at the time. In a sense, Malcolm was one of the first celebrity business people. And that publicity was very helpful for him in advancing the profile of the magazine, which became a magazine that wasn’t just dry business news but made stars out of business people.”

The rich lists continue to exert a strange power over its denizens.

“I am sometimes extraordinarily shocked that these people bother with us so much,” said Forbes’ Luisa Kroll, noting that some billionaires personally have sent her their bank statements while others have emailed her late at night in their efforts to lobby for valuations. “There are definitely people who could care less, but I find it particularly interesting that some of these people—who really have reached the pinnacle of success—care still.

“I have this whole theory that to be that successful, there’s gotta be something quirky driving you—something that makes you a little bit different. That kind of hyper-drive, or that insecurity, or the desire to be at the top—whatever it is—really drives a lot of these people.”

—with additional reporting by Lachlan Cartwright