Shortly after September 11, 2001, then President George W. Bush spoke directly to Muslims. “We respect your faith,” he said, calling it “good and peaceful.” Terrorists, he added, “are traitors to their own faith, trying, in effect, to hijack Islam itself.”

Recently, TODAY’s Matt Lauer reminded Bush of his words. “I understood right off the bat, Matt, that this was an ideological conflict—that people who murder the innocent are not religious people,” Bush explained.

Those words epitomize an important, but controversial question: is someone who acts violently in the name of a faith truly a member of that faith? According to recently highlighted data from the Public Religion Research Institute (PRRI)—which focuses primarily on Christian responses to that yes/no question—potential answers may result in a “double standard.” Christians are more likely to say that other Christians acting violently are not true Christians, while failing to provide the same latitude for Muslims.

But how closely does this represent the reality? When I asked Christian theologians the why behind that simple survey, the answers were—perhaps surprisingly—more complicated and diverse.

According to PRRI, 50 percent of Americans in general say that violence in the name of Islam does not represent Islam—75 percent say the same of Christianity. The numbers shift, however, the more specific the demographic gets, creating the alleged “double standard.” White mainline Protestants (77 percent) and Catholics (79 percent) reject the idea that true Christians act violently, with 41 percent and 58 percent respectively being willing to say the same of Muslims.

White evangelicals stand out the most, having what PRRI calls the “larger double-standard”—87 percent disown Christians who commit violent acts, with only 44 percent willing to say the same about Muslims.

Many, however, believe that Christians who commit acts of terror are overlooked in the West—that “terrorist” is a biased word used only of non-white violent acts done in the name of Islam.

Early in February, the White House issued a report of 78 terror attacks the Trump administration says were ignored by the media. The list was widely dissected by the press and pundits, with news outlets challenging the claims (listing their own coverage as proof), taking the metaphorical red pencil to the list’s many clear spelling errors, and noting the conspicuous absence of attacks by professed white Christians. Notably, the list did not include the recent attack on a mosque in Quebec, as CNN’s Jake Tapper pointed out.

Understandably, most people are unlikely to associate willfully with anyone who acts horribly in the name of a faith they love. When terrorist attacks do occur, faith representatives frequently waste little time in denouncing them (PRRI’s “double standard”) but not all are sure that these open repudiations represent the reality.

Reverend Susan Thistlethwaite, professor of theology at the United Church of Christ’s Chicago Theological Seminary, for example, believes there is value in calling violent actors by their chosen faith.

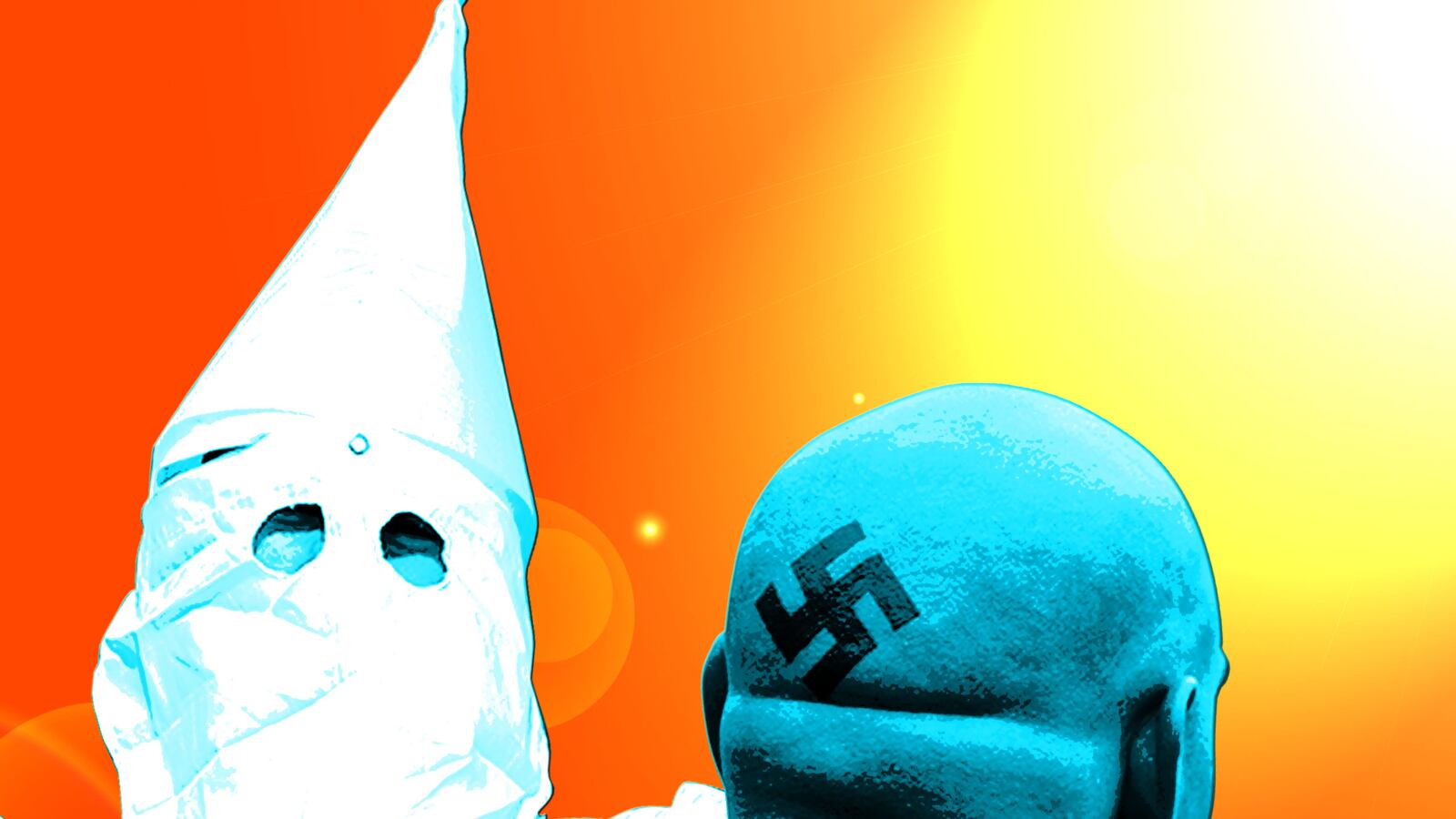

“Christians who commit terrorists acts in the name of their religion are, of course, Christian terrorists,” she says. This does not mean that “Christianity is only a violent religion,” but “it has been complicit in horrific and systemic violence across history, from the Crusades to the Inquisition to the Nazis, and today’s Ku Klux Klan and neo-Nazis.”

She believes it is important that Christians face the issue honestly. “Christians don’t get a ‘hall pass’ to go innocently through the bloody history of what has been done by Christians in the name of Christianity over time. It is absolutely critical that Christians not turn away from the Christian theological elements in such religiously inspired terrorism.”

The same goes for Islam, she says.

“When Muslims commit horrific acts in the name of their religion, I do not think they cease to be Muslims.” She recognizes that Muslims who distance themselves from ISIS might say, “That’s not Islam,” but she believes it is more complicated than that.

“I know many thoughtful Muslims who know they need to dig deeply into their own faith in order to look at the temptations to violence, such as thinking you are doing the ‘will of God’ when what you are really doing is using Islam in order to gain political power.”

Daniel Kirk, pastoral director at Newbigin House of Studies, agrees that violence does not negate one’s Christian or Muslim status.

“Each religion and every religious text holds potential for harm as well as good. Acts of violence can be, and often are, religious expressions. It is critical that we recognize the human component involved when religious communities shape behavior. If we deny the religious component we misinterpret the action and lose our opportunity to respond to it appropriately.”

When shooters (or potential shooters) like Dylan Roof, Benjamin McDowell, Robert Doggart, and Robert Dear, identify themselves as Christians, many might hope to rescind their membership or say it was never valid, but others, like Kirk, believe that approach is problematic.

“Unless a person is being intentionally deceitful, someone who claims to be acting on the basis of religious fervor should be treated as an adherent to that religion. I do not get to judge whether or not a person is ‘really’ of their faith. As a Christian I can only try to persuade other Christians as to why certain behaviors are incompatible with the Christian faith.”

Others believe that the difference between Christians and Muslims is more distinct—that the religion of Jesus rejects violence, but that Islam does not.

“The alleged double-standard claimed by the PRRI survey essentially dissolves when we consider the example and teachings of the respective founders, Jesus and Muhammad,” says evangelical professor Paul Copan, Pledger Family Chair of Philosophy and Ethics at Palm Beach Atlantic University. “Jesus repudiated violence—that is, the unjust use of force—done in his name.”

“By contrast, Muhammad himself engaged in violent, ruthless actions during his career,” he adds. “He taught such ruthlessness as normative in the Quran.”

While agreeing with the larger results of the survey, Copan says the discussion has layers, noting particularly the role of Christians in the military who—assuming they have a just cause—may have to kill. They are in a different situation. It is also possible, he says, for “misguided” Christians to act violently (and therefore, “unjustly”), even if it is contrary to the faith.

When it comes to Islam, he adds that he’s known “plenty of gracious, hospitable Muslims” who “repudiate violence done in the name of Islam” by “screening off any violent texts of the Quran,” though he can’t say that violence in the name of Islam is inconsistent with the faith.

Evangelical J. Robert Douglass, associate professor of theological studies at Winebrenner Theological Seminary, takes a cautious approach to the question, recognizing that both faiths have sacred texts that could be understood violently.

“My understanding of the Christian faith does not permit violence in the name of Christ,” he says. “However, I am not prepared to say that a person who acts in a way contradictory to the teachings of Christ is excluded from being a Christian.” He recognizes that there are complications behind violence, like ignorance, manipulation, and mental illness.

“If behaving in opposition to the teachings of Christ kept one from being a Christian, I could not consider myself one.”

He admits that due to competing factions in Islam with varying interpretations vying for “authentic representation”—some advocating violence and others peace—the question is more difficult to answer “definitively.”

“Both the Bible and the Quran have passages that advocate violence, at least within particular historical contexts,” says Douglass. He says he doesn’t find “a sizable faction within Christianity that is still explicitly advocating the legitimacy of violence in a manner that we presently see in Islam,” but “since Christianity had a historical head start, perhaps in 500 or 600 years this will no longer be true for Islam either.”

Other theologians readily reject the face value of a faith label attached to an act of violence, agreeing with Christians or Muslims who say, “That’s not my faith.”

Greg Boyd, senior pastor of Woodland Hills Church in St. Paul, Minnesota and an outspoken pacifist, finds himself taking a very different stance, saying that anyone—Christian or Muslim—who acts out in violence is not truly a part of those faiths.

“Jesus made one’s commitment to refrain from violence, and to instead love and bless one’s enemies, the precondition for being considered ‘a child of your Father in heaven’ (Matthew 5:39-45). Though followers of Jesus are never allowed to judge another person’s heart or ‘salvation,’ Jesus’ teaching rules out killing another human for any reason, let alone doing so as an act of terror in his name!”

“While the Quran allows Muslims to take the lives of others under certain conditions,” he adds, “these conditions rule out murdering innocent people to install terror in others (6:151). I therefore side with the majority of Muslims who do not consider Islamic terrorists to be true Muslims.”

The briefest dive into this conversation about religious identity quickly reveals an undeniable mosaic of views. And—perhaps to the surprise of some—it should be noted that the flipside of this conversation among Muslims may result in conclusions similar to these Christian perspectives.

“If someone claiming to be Christian commits an act of violence in the name of Christianity,” says Harris Zafar, National Spokesperson for Ahmadiyya Muslim Community USA, “it certainly cannot be my place as a Muslim to decide whether or not that person is a true Christian.” He sees that as “the burden” of his “Christian friends,” though he does believe violence contradicts the “teachings of Christianity.”

“And to be honest,” he adds, “the same holds true with regards to a Muslim. As a Muslim, if I were to look at those Muslims who commit horrible acts of violence and terrorism and say they are not real Muslims, I’m committing the ‘no true Scotsman’ fallacy.”

The goal of Islam is not to judge others, he says, noting that the Prophet Muhammad saw such actions as a “sin.”

Instead he “would focus on highlighting all of the teachings of Islam that this person is violating. And Muslims who commit acts of terror can certainly call themselves Muslims if they would like, but I can easily illustrate the fundamental teachings of Islam that they are starkly violating.”

Islam, says Zafar, calls its adherents to “stop that injustice” and “unite people together through a bond of humanity and mutual respect—not to divide people with injustice or violence.”

Undeniably, this is a conversation and debate with years of life left in it. The diversity of opinion belies the reality: there is no such thing as a single or simple Christian perspective on how to understand violence and religiosity.

It was former president and self-professed Christian, Barack Obama, for example, who once offered a similar sentiment to that of Bush. When asked in a CNN town hall why he wouldn’t use the words “radical Islamic terrorist,” he said didn’t want to lump “these murderers” with the world’s billions of peaceful Muslims.

“There is no doubt that these folks think and claim that they are speaking for Islam,” he said, “but I don’t want to validate what they do. If you had an organization that was going around killing and blowing people up and said, ‘We’re on the vanguard of Christianity.’ As a Christian, I’m not going to let them claim my religion and say, ‘you’re killing for Christ.’ I would say, that’s ridiculous.”