On September 3rd of this year Kurt Schrimm, Germany’s special prosecutor for investigating Nazi-era crimes, recommended bringing charges against 49 men and women who allegedly served as guards at Auschwitz. In the German system, the special prosecutor reviews potential cases and recommends for action only those that meet the highest standards of evidence. It is then up to local prosecutors where suspected criminals live to mount cases or not.

What’s the use of prosecuting people, now in their mid-eighties to nineties, who will be moribund or dead by the time of their trials? Why re-open a story that’s already been so fully told, especially when the millions spent on prosecution could be better spent teaching children to recognize and resist fascism? Such objections are reasonable. But Germany and the world have a compelling interest in pursuing these people even if they never see the inside of a courtroom. Not only does justice demand it; their trials would offer a much-needed reminder as the last perpetrators are dying off.

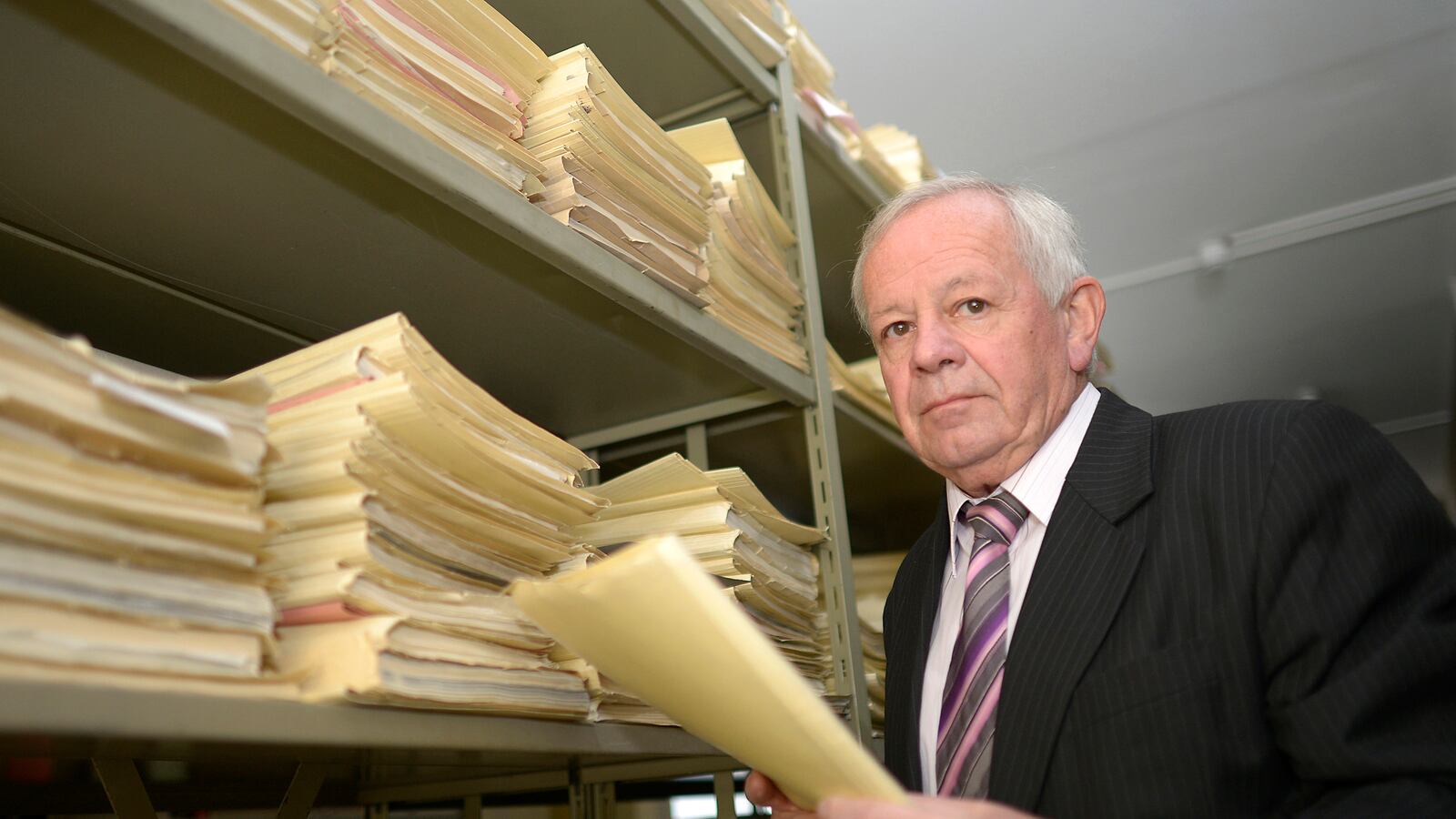

Schrimm based his recommendations on the work of historians at the Nazi Archive in Ludwigsburg, Germany. Located in a former women’s prison, the Archive houses one of the largest catalogs of misery ever assembled. The particularity of the crimes documented there is what most chilled me on a trip to Ludwigsburg to research a book. There’s one document I won’t soon forget: a commendation for a soldier who’d shown special zeal for shooting Russian prisoners in the neck.

The existence of such records defies logic. If you’re going to murder dozens of people or praise someone for the deed, why leave a record and risk later exposure? Because the Nazis didn’t think of themselves as criminals, nor did they expect to lose the war. They understood the task of extermination was difficult, and they wanted a record of the hard but necessary work to purify the race. They believed that two hundred years into the thousand-year Reich, the executioner’s great-great-grandchildren would stand over his grave with pride for his having sacrificed so that his descendants could live in a world free of Jews and Slavs. It’s one of history’s grim ironies that documents meant to glorify Nazis have become weapons used to destroy them.

When you approach the Archive in Ludwigsburg, you find high stone perimeter walls, original prison cell windows swapped out for bullet-proof glass, steel gates, and multiple security cameras set on motorized swivel mounts. These days, the government no longer aims to keep prisoners from breaking out but rather neo-Nazis from breaking in and torching the place. They’d like nothing better, for there’s treasure in this drab building: government-issued cabinets stuffed with color-coded files detailing names, dates, and numbers. Proof, in a word, that the Holocaust was real. You don’t find body parts in the Archive; but if you close your eyes and give a thought to what those numbers mean, you don’t have to do much imagining.

If history is any guide, the latest call to try Nazi perpetrators won’t succeed. In the thirty years after the war, the Federal Republic of Germany mounted 85,802 proceedings against those suspected of Nazi-era crimes. A full ninety percent, nearly 80,000 cases, led to nothing. Of the relatively few convicted, only 14 were sentenced to death and 166, to life terms.

Why then pursue these prosecutions? On the one hand, we have the absurdity of spending millions to convict suspected guards who either won’t survive a trial or more than a few years of incarceration. On the other, we have a record of failure to convict. The entire effort seems futile.

But it isn’t. Elie Wiesel and others remind us that the Nazis murdered individuals, each with a name and a life. Each murdered, multiplied by millions. The mind can barely hold it. The Ludwigsburg Archive makes a parallel claim: that it wasn’t the Nazi war machine that killed but individuals in the machine who did the killing: particular men, with names, men who joked and drank sudsy beer in their off hours, who also dropped gas canisters through the slots and shot children into freshly dug graves. The Archive’s documentation of pain and perversion should become a World Heritage Site; for it is nothing short of an essential, obscene gift from the Nazis to present and future generations of what we can become.

We must seize every chance we can to remember that evil is an individual act, not a systemic one. We’re seventy years removed from the war and, soon enough, the Archive will be the domain of historians only. Prosecutors should try any perpetrators who can be caught, whatever their age. Force them to stand and face history. More important, remind us of what we’re constantly forgetting: regimes don’t kill, individual men and women who’ve given their souls to regimes kill. If we’re going to change things, we could do worse than to begin there.