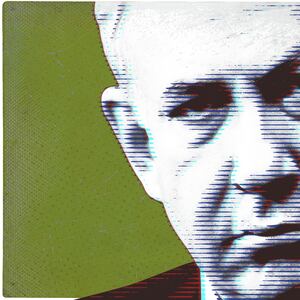

Startling new charges recommended by the Israeli police threaten to blow open the secrets of its entire leadership caste, including a cousin of prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu and the dashing former commander of its navy.

These are all men much more accustomed to the shadows.

The last time Maj. Gen. Eliezer Marom had a brush with scandal was in 2009, while serving as Commander of the Israeli navy.

The well-known officer was seen by passersby at the Go-Go Girls strip club in downtown Tel Aviv “smoking a cigar, drinking alcohol and surrounded by bare-chested women” in the words of Yediot Ahronot, the tabloid that published a breathless report the next morning.

That time, Marom got away with the tittering of Tel Aviv café goers, a verbal reprimand from the army chief of staff and a written apology.

This time, Marom, now a highly decorated retired officer, finds himself embroiled in a scandal of entirely different dimensions, accused of taking $160,000 in bribes.

He is one of six men connected to Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s inner circle who the police recommend should be indicted for bribery, money laundering and other misdeeds allegedly aimed at directing one of Israel’s largest naval acquisition deals for personal gain.

Netanyahu is not a suspect in the procurement scandal, known in Israel as the “Submarines Affair,” but several months ago the police recommended he be charged with bribery, fraud and breach of trust in two other corruption probes.

Formal charges can only be brought by the attorney general, serving as state prosecutor, who has yet to decide on any of the cases.

But it is impossible to avoid the metaphor of a noose tightening around Netanyahu. Also ensnared are the prime minister’s cousin and confidant, David Shimron; his former chief of staff ,David Sharan; and retired Brig. Gen. Avriel Bar Yosef, his 2016 nominee for the post of national security advisor.

Bar Yosef was forced to withdraw his candidacy as, unbeknownst to the public, he faced the police investigation.

Rounding out the crew are former minister Eliezer Sandberg, whom Netanyahu appointed head of the powerful Keren Hayesod, a quasi-governmental organization that raises funds for Israel abroad; and reserve Brig. Gen. Shay Brosh, former commander of the ultra-élite naval commando unit Shayetet 13.

Shimron, a discreet behind-the-scenes operator and a blue-chip lawyer, is the least likely figure to be caught up in a sprawling, unseemly, bribery case involving the multibillion-dollar purchase of submarines and missile boats from Germany.

Two years younger than the prime minister, Shimron grew up in the same élite Jerusalem milieu as the Netanyahu brothers. His father, Erwin, served as Israel’s second state attorney.

He has represented the notoriously untrusting Netanyahu in legal and political matters for more than four decades and at least once, he had the lead role resolving an intensely personal concern: in 1993, Shimron handled Netanyahu’s delicate negotiations with his wife, Sara, after the revelation of an extramarital affair with a campaign aide.

Tall and publicly taciturn, Shimron denies any wrongdoing. On Thursday, he said, “I’ve committed no crime. I am confident that the case will prove to be groundless and no indictment will be filed against me.”

He is nonetheless at the heart of the scandal, which first exploded into public view in November 2016, when investigative journalist Raviv Drucker revealed he had evidence proving Shimron had aggressively lobbied Israel’s defense ministry to choose the German concern ThyssenKrupp Marine Systems for the procurement of vessels Israel needed to protect its offshore gas fields.

The attorney general ordered an immediate police investigation.

Shimron’s defiance of regulations requiring sealed international proposals for a multibillion-dollar deal raised concerns from the defense ministry’s counsel, whom Shimron allegedly called to ask why an international tender had been issued, as regulations require.

Ahaz Ben-Ari, the ministry’s legal adviser, immediately reported the call from the prime minister’s ubiquitous right-hand man to his boss, the ministry director general.

Shimron, it quickly emerged, represented not only Netanyahu, but also Michael Ganor, ThyssenKrupp’s agent in Israel, a client of the top Jerusalem firm Shimron, Molho, Persky & Co.

“I was …called by attorney David Shimron, who represents the ThyssenKrupp Consortium,” Ben-Ari reported in an email dated July 22, 2014, “who wanted to know if we were stopping the tender procedures in order to negotiate with his clients, as was requested by the Prime Minister.”

Shimron and Netanyahu both deny having knowledge of the other’s actions, Shimron claiming he was acting only on behalf of the German company when he made the call, and Netanyahu asserting his “only consideration” was the security of the state of Israel.

At the time, Shimron insisted he had “not spoken with any state officials about the privatization of the naval shipyard, nor … dealt with any state officials about vessels purchased by the State of Israel.”

Given the importance and vulnerability of Israel’s offshore fuel infrastructure, and the possibility that the submarines have a second-strike capacity against a potential attack from Iran, many Israeli analysts speculate the Mossad, Israel’s intelligence agency, had to have approved the deal, and could not have done so without the consent of the prime minister.

In 2017, after Shimron was briefly put under house arrest in connection with the probe, Netanyahu tried to put some distance between himself and his lifelong friend, informing journalists who accompanied him on a trip to Hungary that Shimron was his second—not first—cousin.

On Thursday, the police asserted that Shimron abused his “status and proximity to the prime minister” to advance Michael Ganor’s interests as ThyssenKrupp’s representative.

In exchange, the police says Shimron received nearly $75,000 for influencing officials and greasing the skids.

Ganor turned state’s witness in 2017, signing a plea limiting his legal exposure to charges of tax evasion and his potential sentence to no more than 12 months in prison, in addition to a fine of about $2.7 million.

Tweeting on Thursday, former prime minister and former army chief of staff Ehud Barak, who is no fan of Netanyahu, said the entire affair amounted to “Netanyahu's downfall and the betrayal of state security.”

If Netanyahu knew, Barak posted, “his place is in jail. If he didn’t know, he's not qualified to lead a country.”

“Treason, shame and disgrace,” he concluded.

ThyssenKrupp, which has always contended Ganor hired Shimron without the company’s approval, said on Thursday that “the information at our disposal comes only from the media; we have received no other official information. As soon as we know all of the facts, we will consider additional measures in the framework of the legal options available to us.”

If wrongdoing is found, the entire submarine deal, one of Israel’s most significant military acquisitions, will be annulled.

A spokesman for Germany’s chancellor Angel Merkel, who also had to sign off on the deal, said she was ”surprised by the new details" in the police report and that ThyssenKrupp “would rather lose a deal than be involved in anything dirty.”

The police said David Sharan, who served as Netanyahu’s chief of staff from 2014 to 2016, accepted about $35,000 from Ganor starting in 2013, when Sharan worked in the finance ministry.

Bar-Yosef is charged with assisting Ganor to get the job representing ThyssenKrupp in order to get a percentage of his earnings from the deal.

Zandberg allegedly opened his rolodex for Ganor, introducing him to senior officials and illegally transmitting insider information, for which he received a payoff of about $27,000.

Netanyahu has made no comment since the police announced the extensive conspiracy.