On February 15, 2012, Italian navy marines Massimiliano Latorre and Salvatore Girone were on lookout duty as anti-pirate armed guards aboard the Italian-flagged Enrica Lexie oil tanker as it traveled from Singapore to Egypt. They had just entered Indian waters some 20 nautical miles off the shore of Kerala, India, when the marines say they spotted a rogue-looking 14-meter vessel called the St. Antony on a collision course heading straight towards them.

Indian waters are the third most dangerous pirate-infested seas in the world, after the coasts off Africa and Southeast Asia, and there had been a number of violent attacks in recent weeks, which is why the Enrica Lexie had sought the help of the Italian navy for protection. The Italian marines had been trained to spot and ward off pirates and they say that the boat coming towards them fit all the characteristics. Latorre, who was the chief sergeant of the six-member security team onboard the Enrica Lexie, fired off 12 warning rounds from his automatic weapon into the water near the boat while Girone fired off eight.

But, unbeknownst to the Italians, the men in the boat—identified as Ajesh “Pinky” Bink and Jelestine—were not pirates after all. They were fishermen guiding a boat full of fresh tuna and ten sleeping crewmembers who had retired to the sleeping quarters below deck after a long week trawling the seas. And the warning shots proved fatal, hitting and killing both men within a few minutes. The fishing vessel’s captain, called Freddy, took control of the boat after the men were killed at the wheel. He later told investigators that “it was raining bullets” as the marines kept shooting while the fishermen tried to make their escape.

The Indian coast guard was called and a few days later, they intercepted the Enrica Lexie and guided it to the port of Kochi. Once they matched the bullets that had killed the dead fishermen to the weapons belonging to Girone and Latorre, the two Italians were taken off the ship and placed into custody. Before the arrests, the Italian navy had defended the men, lauding them for warding off pirates and protecting the Italian vessel. But soon it became apparent that the Indian officials saw things in an entirely different light. The men were put under investigation for murder, attempted murder, maritime mischief and intent to harm. According to Indian media reports, the Italians were accused of carelessly shooting like “cowboys at sea”.

The men have still not been charged, and on February 18, nearly two years after the incident, India’s Supreme Court in New Delhi will rule on whether to charge the men with manslaughter under anti-piracy and anti-terrorism legislation. The use of anti-terrorism laws to charge military men who were actually fighting terrorism and piracy has angered Italian and European Union officials, who say India is out of line. In a senate hearing dedicated to the case on Thursday, Italy’s foreign minister Emma Bonino did not mince words. “This is no longer a dispute between Italy and India,” she said. “This is a global problem now. India is playing with the application of the anti-terrorism laws in an increasingly dangerous game.”

India does not agree. They say that the Italians were careless with the use of armed guards aboard the vessels. The practice of using military protection for civil transport is a contentious topic for nations like India and Africa, who say the procedure is unregulated. Indian’s foreign minister Syed Akbaruddin says the Italian military incident could set the precedent going forward when it comes to patrolling the seas. “This is a unique case without precedence anywhere in the world,” Akbaruddin told Indian reporters outside of the New Dehli courthouse where the Supreme Court heard arguments earlier this week. “We can understand how our Italian friends might be confused or misinterpret this legal proceeding, but this is a matter that must follow our legal system under our sovereign authority.”

According to local press in New Dehli, the captain of the Enrica Lexie had not asked for permission to cross Indian waters with armed military on board. And upon interviewing the Enrica Lexie captain, the Indian investigators claim that the Italian marines had not followed proper procedure. According to the scant court documents in the case, Umberto Vitelli, the ship’s captain, apparently told Indian investigators that neither he nor the four crew members had been made aware that their ship was under attack by suspected pirates. Only after he heard the shots fired, Vitelli reportedly said, did he sound the ship’s alarm because he didn’t know where the shots came from or what provoked them, according to Indian media reports. Vitelli’s lawyers in Naples, the Enrica Lexie’s home port, say that the interrogation wasn’t exactly that clear and that the captain would never make such careless comments without a lawyer present.

The Italian military has released their own version of events, also quoting Vitelli, who they say told them he followed procedure when they spotted the pirate vessel coming towards them by “setting into motion the alarm, flashing search lights and horns,” according to the Italian foreign ministry under Bonino, which is closely following the case. They also say that Indian authorities overstepped their jurisdiction by boarding the Italian vessel to arrest the Italian marines who, they say, were sailing in international waters when the incident occurred.

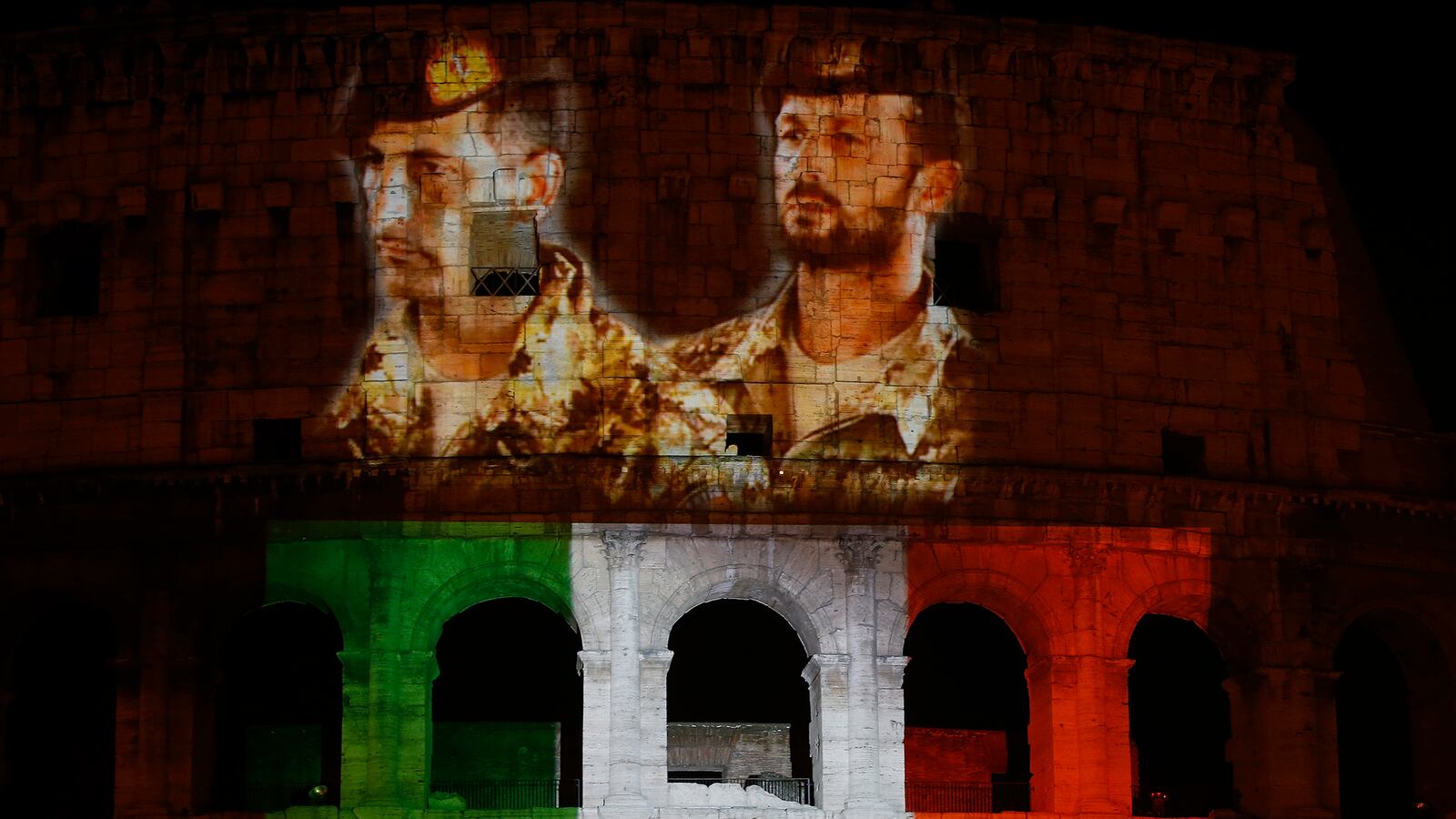

The Italian marines spent 100 days in India’s Travandrum prison with limited access to legal consultation and what they have described as “few modern comforts” before being released to the Italian embassy in New Delhi on a €143,000 bond each with the stipulation that they must check in with local police once a week. They were allowed to return to Italy for a brief visit for Christmas 2012, nearly a year after being taken into custody. They had still not been officially charged with a crime, but investigators said they were moving closer to an indictment. The two men returned to Italy, where they received a hero’s welcome, complete with the president of the Republic meeting them at the airport, which angered the Indian investigators who saw the marines as murder suspects. They returned to India without incident in January 2013.

A month later, in February 2013, the marines—still not charged with any crime—were again given leave to come back to Italy, this time to vote in national elections. But 10 days before they were scheduled to return, Rome said it would not send the military men back to face a trial that could result in the death penalty, which is a common punishment for murder in India. Instead, Italy’s foreign minister at the time said the men would be tried in an Italian tribunal. The Indian government swiftly detained the Italian ambassador to India in response, barring him or his family from leaving the country while the two nations teetering on the brink of a serious international incident. In March 2013, after assurances that India would waive the death penalty should the men be convicted, Rome succumbed and sent the marines back to face trial. The ambassador was then released.

The marines were not given leave to come back to Italy this Christmas and are now awaiting the February 18 by the three-judge panel. In early February, the move by the Indian attorney general to petition the Supreme Court to charge the men under anti-terrorism and anti-piracy legislation has caused outrage in Italy and beyond. “They are marine officers and not pirates. They cannot be tried under the antipiracy law,” the marines’ lawyer Mukul Rohatgi told the New Delhi court earlier this week. “They should be allowed to return home instead.”

At the news of the potential terrorist charges, Italy’s Prime Minister Enrico Letta said, “Italy is not a terrorist country. Any decision to try the two under anti-piracy legislation would be absolutely unacceptable.” He added, “It would bring about negative consequences for [India’s] relations with Italy and the European Union, with equally negative consequences on the global fight against piracy.” He later tweeted, “Italy and the EU will respond.”

The European Union agrees. “The legislation that appears to be used suggests that somehow this is about terrorism,” the EU policy chief Catherine Ashton said in a statement. “And this has enormous implications for Italy but also for all countries engaged in activities that are anti-piracy. I do think colleagues need to now be very concerned.”

The move to try the men under anti-terrorism laws also prompted NATO chief Anders Fogh Rasmussen to call for what he termed an “appropriate resolution.”

“I am personally very concerned about the situation of the two Italian sailors. I am also concerned by the suggestion that they could be tried for terrorism offences,” Rasmussen told reporters in Brussels. “This could have possible negative implications for the international fight against piracy—a fight which is in all of our interests.”

There is also growing concern in Italy that the move to stand tough against the Italian marines could be part of internal Indian politics. The current president of the leading Indian National Congress party is Italian-born Sonia Gandhi, who entered politics on a wave of public popularity several years after her husband, then-prime minister Rajiv Gandhi, was assassinated in 1991. She and her son Rahul are set to launch their joint campaign to stay in power next week. Italian foreign ministry officials have expressed concern that if India is perceived to be soft on the Italians, it could reflect poorly on Gandhi’s leadership ahead of the crucial general elections which are set to begin in late April of this year. When Rome refused to send Latorre and Girone back last February, the Italian-born Ghandi was put under pressure to take a stand against her birthplace. “The trust in the Italian government in the case of the marines and their betrayal of their promise to our supreme court is totally unacceptable,” she told Indian parliament at the time. “No country can or should or is authorized to undervalue India.”

The United Nations has refused to get involved in the matter, despite Italy’s insistence that using anti-terrorism and anti-piracy laws is in defiance of international standards. Ban Ki-moon instead said while he was “surprised” India was considering trying the men under anti-terrorism legislation, the UN would not intervene. “This is a bilateral issue,” he said Wednesday through his spokesman, Martin Nesirsky. The Italians responded by saying that if the UN would not help them by becoming an arbitrator between Italy and India, Italy may reconsider cooperating in UN missions abroad. Italy currently provides peace-keeping troops in 26 UN-led missions in 21 countries. “The story of our two marines is intrinsically tied to our international cooperation,” Italy’s defense minister Mario Mauro said Wednesday. “We must win the tug of war for these men, even if the battle is with the United Nations.”