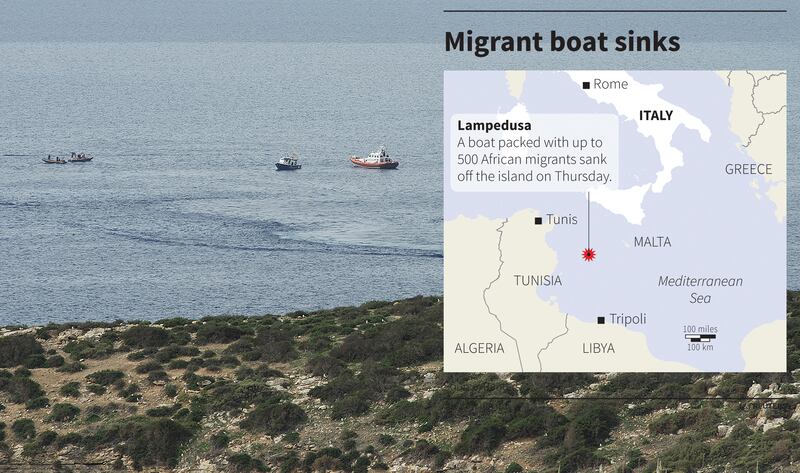

Just before dawn on Thursday morning, a rickety fishing boat with around 500 migrants stuffed onboard started taking on water off the island of Lampedusa, to the southeast of Sicily. The motor flooded and failed and several of the passengers used their cigarette lighters to create light to try to find and fix the leak. A nearby fishing boat sent a distress signal to the Italian coast guard, but not before the boat caught fire from the lighters. In a chaotic panic, those onboard fled the flames and gathered on the safe side of the burning vessel, tipping the boat into the sea just moments before authorities arrived. By midday, 94 corpses had been fished from the water and lined up along Lampedusa’s tiny fishing port. Among the dead were four children and one noticeably pregnant woman. Miraculously, 159 people were saved. But an estimated 250 remain missing at sea, and by now are presumed dead. Of more than 100 women on board, only three survived. Most of the passengers and victims were from Eritrea, Ghana, and Somalia. The disaster is among the worst in a long history of deadly shipwrecks on the island, now known for its tragic naufrages.

Last week, a similar boat arrived on Lampedusa with 398 Syrian nationals on board. One diabetic woman who fell ill on the journey died along the way. Her body was preserved in the ship’s hull, not dumped into the sea. The Syrian boat was no yacht, but it was certainly in a better state than the crippled African vessel that arrived on Thursday. The Coast Guard was able to pull the passengers to safety after someone onboard called a hotel in Lampedusa to see if there were rooms. The hotelier alerted authorities who sent a Coast Guard ship to meet the incoming boat. Unlike the North African migrants, many of whom pay smugglers more than $5,000 for the treacherous journey, the Syrians reportedly only paid half that amount for their passage.

And unlike the North African migrants and refugees, the Syrians readily handed over their identification papers and were whisked almost immediately to the Italian mainland where they were automatically granted refugee status. The North African migrants who survived Thursday’s incident will instead be stuffed into a reception center on the island, built for 350 people, which is already more than 1,000 people over capacity.

ADVERTISEMENT

Earlier this summer, another Syrian boat arrived on a crowded beach on the southern tip of Sicily just as Italians were settling into their summer beach holidays. Italians in Speedos and bikinis were photographed carrying Syrian babies and helping veiled women to safety. Many witnesses to the wreck said some Syrians got off the ship carrying tablet computers and luggage –a stark contrast to the North Africans who arrive in soaked clothing and with nothing but what’s in their pockets.

Some were met by waiting cars, which took them to airports to fly to Sweden, the first European nation to offer asylum and permanent residency to any Syrian refugees coming to Europe. The asylum only applies to Syrians; many of the North Africans are instead deported back to their troubled nations.

Carla Trommino, a lawyer in Syracuse, Sicily, who also heads the Association for the Legal Studies on Immigration to Sicily, told journalists on the scene that the Syrian refugees often have money and are well-dressed. “They try to avoid identification by the authorities because they want to go to Sweden and not end up in the system of Italian refugee centers. We often see relatives waiting with cars on the dock," she said. More than 3,000 Syrian refugees have landed on Sicily since July, according to the United Nations High Commission on Refugees. One Syrian woman gave birth on her journey over the summer; another Syrian woman who died en route gave her family permission to donate her organs when they reached shore, according to the Italian news agency ANSA, which reported that her liver and kidneys were given to three Italian patients.

Even when the Syrians are identified and processed through the standard refugee centers on the Italian islands and mainland, special sections have been created to segregate them from other migrants. Those who do not travel into Europe have found homes in Italian cities. Many have taken jobs and some have even integrated into the expat social circles in Rome and Milan.

The Syrians’ plight illustrates that not all refugees and migrants are treated alike on Italian shores. Of the 26,000 illegal migrants and refugees who have reached Italy so far this year, more than half will be turned back to where they came – no matter how bad things are in those countries. Italy, in the muck of an economic crisis, simply cannot afford to help everyone who lands on the shores. The Italian government on Thursday called for greater European intervention to help shoulder the pressure on the Italians who are struggling to find space for the mass influx of migrants. “This is a European tragedy,” said Angelino Alfano, deputy prime minister to Enrico Letta. “This is about European frontiers, not Italian borders.”

The sentiment was echoed by Pope Francis, who went to Lampedusa this summer on his first papal voyage, at which time he lamented the “global indifference” to those searching for a better life. On Thursday he called the tragedy “shameful”, calling for action. “Let us join forces so these tragedies never happen again.”