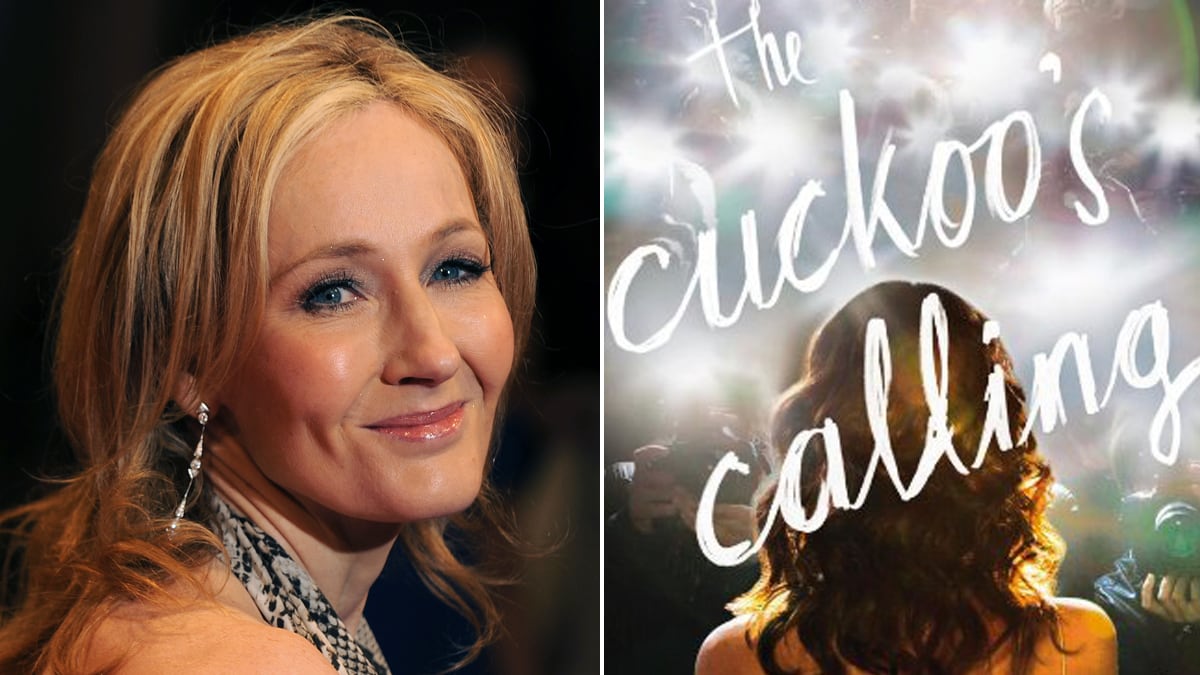

It must have been fun while it lasted, but now J.K. Rowling is back to square one. In a new statement on her website, she comes clean as the perpetrator of one of the best literary hoaxes in recent memory: in April, in collusion with her English editor, she published a detective story titled The Cuckoo’s Calling under the pseudonym Robert Galbraith. The novel was enthusiastically endorsed by such high-profile crime writers as Val McDermid, even though they had no idea who the real author was. It also got excellent reviews. Then last weekend the Sunday Times broke the story of her authorship, and Rowling quickly fessed up.

But the most fascinating part of her explanation on the website addresses her motivation: “It has been wonderful to publish without hype or expectation and pure pleasure to get feedback from publishers and readers under a different name.” In other words, she got to slip the yoke, at least for a little while, of having everything she ever wrote judged in light of the Harry Potter books. Clearly the fact that novel had sold about 450 copies in England, according to The Guardian, didn’t bother an author who is already one of the wealthiest people on the planet. What gratified her was that critics and other novelists embraced her book with no idea as to who actually wrote it. Now, of course, the news is out, The Cuckoo’s Calling is the No. 1 bestseller on Amazon, and J.K. Rowling is back to being J.K. Rowling. So the fun’s over, at least for her.

I have no idea what I would have thought of The Cuckoo’s Calling had I read it without knowing who actually wrote it. If I’d believed, like those early critics, that I was reading a first novel by a former British military policeman, I’d have probably been over the moon, too. Instead, I knew all along I was reading a Rowling novel, so my expectations were pretty high from the start.

I wasn’t disappointed. Whether she’s writing about Dementors or detectives, Rowling is a pro. The Casual Vacancy, her dark and savage satire of small-town life and her first adult novel, though not perfect, proved that she could also write for an audience whose favorite drink is not the juice box. That novel’s real problem was that it tried too hard; there was something self-conscious about it, something too tightly wound. The Cuckoo’s Calling is much looser, more relaxed, more fun, and as a result a much better book. And Cormoran Strike is a private eye whose company I would share again no matter whose name is on the dust jacket.

Strike joins that long list of tough-guy detectives who are incorruptible men much smarter than their bank balances would indicate. A former military-police detective who lost a leg in Afghanistan, Strike has set up shop as a London private eye, but he has only two clients, one of them so disgruntled that he’s taken to sending Strike death threats, and most of the detective’s time is spent dodging his creditors. Then a wealthy lawyer comes calling, and the game’s afoot.

John Bristow wants Strike to find out what really happened to Bristow’s sister, a supermodel named Lula Landry who died after falling from a four-story apartment building. The police called it suicide; Bristow believes it was murder.

One of the great features of crime fiction is that a detective can go anywhere, from the mansions of the wealthy to the hovels of the poor. If you want to read novels that portray a cross-section of society today, you’re probably reading George Pelecanos or Kate Atkinson. Dickens, who created one of the first great detectives in Inspector Bucket, would surely salute Cormoran Strike, whose relentless digging takes him—and us—into posh law offices, drug clinics, high-fashion photo shoots, pubs, police stations, and chic nightclubs (including the drolly named Uzi).

The plot of The Cuckoo’s Nest is so complicated that it takes Strike about 15 pages to explain what happened at the end. It reminded me of the story about William Faulkner and Leigh Brackett writing the screenplay for The Big Sleep. In the midst of translating Raymond Chandler’s novel to the big screen, they couldn’t figure out who killed the Sternwoods’ chauffeur and dumped him and his limousine into the Pacific Ocean. So they called Chandler and asked him. He couldn’t figure it out either. If Faulkner and Brackett had been writing the screenplay for this novel, they’d have called more than once.

But who reads The Big Sleep for the plot? You read it to tag along with hardboiled detective Philip Marlowe. It’s the same with The Cuckoo’s Calling, whose chief attraction first and last is Strike himself, a tall, lumpish man so decidedly unhandsome that Rowling describes him at one point as a “boxer Beethoven.” In classic private-eye style, he drinks, smokes, is unlucky in love, and so poor that he lives in his shabby office, where he can barely afford his temp secretary, Robin (who emerges as a delightful Watson—a very smart one, it turns out—to his Holmes). The missing leg is only the most obvious sign that Strike is damaged goods, a loner wounded by life long before he went overseas. But if he can’t heal himself, he has no trouble seeing into the dark hearts of the people he encounters, and it’s this blend of vulnerability and acuity that makes him such good company.

Rowling has always loved playing with names and language, and in this novel she just goes on a tear, never using one adjective when she can use two (“paunchy and mottle-faced,” “bloated and distended”). She’s especially keen on baroque words for people’s eyes (“chrysoberyl eyes,” “marmoset eyes”). But she hits the mark more than she misses, e.g., a debauched rock star is described as looking like “a Pierrot gone bad.” And now and then, this fondness for words, coupled with a near-flawless ear for dialect, produces prose that takes your breath away.

“She wuz depressed,” says Rochelle, one of the dead woman’s friends, a lower-class addict. “’It’s an illness,’ she said, although she made the words sound like ‘it’s uh nillness.’

“Nillness, thought Shrike … Nillness, that was where Lula Landry had gone, and where all of them, he and Rochelle included, were headed. Sometimes illness turned slowly to nillness, as was happening to Bristow’s mother … sometimes nillness rose to meet you out of nowhere, like a concrete road slamming your skull apart.”

The Cuckoo’s Calling may be a little too long (Rowling seems constitutionally incapable of writing a short book), and a little too complicated. But the author never stops having fun, and neither do we, right to the end. Indeed, the best joke in the book occurs in the “About the Author” section at the back: at the end of the author bio (“Robert Galbraith spent several years with the Royal Military Police,” etc.), we come upon the very last line: “’Robert Galbraith’ is a pseudonym.” You can’t say she didn’t try to warn us.