When the British went to war exactly 80 years ago they swiftly lost the individual freedom to make fundamental choices over the way they lived.

Freedom of travel, freedom to choose work, freedom to remain where they lived, freedom to choose a school for the kids, freedom to buy the clothes they wanted, even the freedom to decide how many books were printed, how many movies were made, and what kind of news could be reported and what could not—all gone.

That’s what being on a war footing meant. The state became all powerful. In order to survive, we were told, individual choice was a luxury Britain could no longer afford.

And there was one other curtailment of individual choice that touched every home in the land: what people could eat.

In war Britain’s position as an offshore island of Europe had an upside and a downside. The upside was that invasion by land was impossible. The downside was that the population could not be fed from the island’s own resources.

Hitler understood that vulnerability. He set out to starve the British by sending swarms of submarines into the north Atlantic to wreak havoc on convoys bringing food from Canada and America.

In the decade before the war Britain imported around 22 million tons of food a year, almost two-thirds of its food supply. During the war that was halved, to around 11.5 million tons.

But the British never starved. In fact, they ate the healthiest diet they had ever enjoyed.

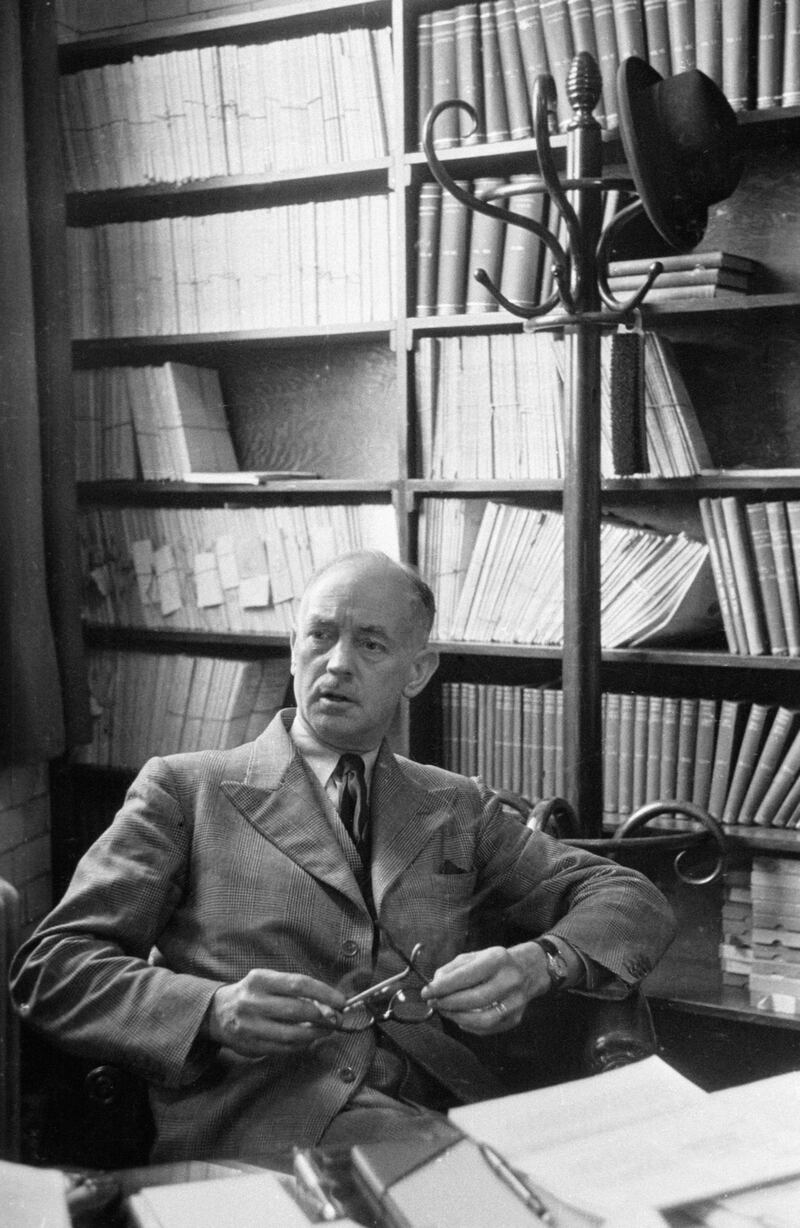

This was made possible largely by the work of one man, a biochemist named Jack Drummond. In a classic example of the right man being in the right place at the right time to acquire absolute power over a policy, the arrival of Drummond as scientific adviser to the Ministry of Food in 1940 has few equals.

Quite simply, Drummond laid down the daily menus for the whole country.

Sir Jack Drummond, wartime adviser on nutrition, now research chief of Boots, Nottingham.

Kurt Hutton/GettyBut his power extended beyond that. He decided what foods should be imported and what should not. He ordained a new balance between imported foods and home-produced foods, limiting imports to essentials and specifying what Britain should provide more of for itself.

Only in wartime and with a leader as responsive to scientific arguments as Winston Churchill could one man with a rigorous doctrine of his own have cut through all the bureaucracies, vested interests and red tape with such speed and results.

After the war the American Public Health Association, citing Drummond for an award, said his work was “one of the greatest demonstrations in public health administration that the world has ever seen.”

But Drummond had a conviction and personal authority that was hard to challenge. He gained recognition by advancing the knowledge of how vitamins worked, first as a pupil of a Polish biochemist, Casimir Funk, who coined the word “vitamine” while working at the Cancer Research Institute in London.

Drummond, dropping the final “e,” identified and named vitamins A, B and C. At the age of 31 he became the first professor of biochemistry at University College London.

But then, with the help of a young research assistant, Anne Wilbraham, Drummond began a personal journey into the subject that really fascinated him: What the British ate and why they ate it. The two of them produced a book, The Englishman’s Food, that covered 500 years of British gastronomy, such as it was.

It turned out to be a scientific skewering of centuries of bad diets and the ravages of public health that they caused, a kind of founding thesis for a science not yet fully embraced: nutritionism.

To read the book is to take a view of a country that is a living, crazy montage of malnutrition and gluttony.

For example, an 18th-century “country gentleman” sat down to a typical dinner: First course of cod, some mutton, some soup, a chicken pie. Second course pigeons and asparagus, fillet of veal with mushrooms, roasted sweetbreads, hot lobster, apricot tart. Dessert a pyramid of syllabubs and jellies with white port.

The working-class dinner of the same period was, if you were lucky, a shin of beef, a small beer and a slice of bread.

Drawing from a mountain of anecdotal evidence Drummond concluded that between these two extremes the British could and should have a diet that, at the very least, met basic daily energy requirements. That, he said, meant for an active young man a diet that provided 3,200 calories a day and for a woman about 2,300 calories.

As the book was delivered in 1939 Drummond had a personal crisis to handle. His marriage broke up. He and Wilbraham had become lovers while they worked on the book, and after he was divorced they married in 1940, just after he was appointed diet supremo.

I still clearly remember the day when food rationing began in January 1940.

Every family was issued with a ration book that contained coupons, the size of postage stamps. The coupons were not money. Their worth was determined by the quantity and type of food they could be exchanged for, and that value constantly changed depending on the food supply – for example, according to what cut of meat and what weight was available each week.

My mother flipped through the pages—the books were printed on cheap, coarse paper—and tried to figure out the system. This was followed by regular arguments with the grocer, the butcher and the baker about what we were entitled to have.

Three young children enjoying a portable, healthy snack - a carrot on a stick. Ice cream is not available due to war rationing.

Ashwood/GettyAnd, as with any such imposition, people found ways around it. The officially approved way was to grow your own stuff. Anyone with a garden or a so-called “allotment”, a strip of nearby land available for cultivation, could get the seeds to grow vegetables.

We had both a garden and an allotment and my father, who grew up on a farm, had green fingers. Everything he planted flourished. But this brought its own problems. There was far more of some things than we could eat – for example, I was assigned to sell off surplus of carrots. And the vegetables were limited to their seasons, so for large parts of the year we would never see a carrot or a tomato.

My father also had the skills of a nocturnal hunter-gatherer. He frequently disappeared with a small rifle and came back with a brace of rabbits or a hare. I became a big fan of my mother’s rabbit stew and only encountered a superior version once, decades later, in Tuscany.

Other people were less scrupulous. A neighbor was arrested after a schoolteacher asked his two kids why they hadn’t had a bath in two months. The kids, with dangerous candor, disclosed that the bathtub was occupied by half a side of a pig that was curing.

The abiding genius of Drummond’s doctrine was the way that it governed how fluctuating food supplies were managed to guarantee that the basic diet (if rabbits were not available) was healthy.

To cut back on imports of wheat a “national loaf” was produced, virtually a whole-grain bread that retained all the key nutrients in the flour, with calcium carbonate added to provide the calcium; vitamins A and D were added to margarine as a healthier substitute for butter; and children received a free daily bottle of milk at school. Orange juice, cod liver oil and tablets of vitamins A and D went to pregnant women and small children. (I developed a taste for cod liver oil that has never left me, it’s my elixir.)

When Drummond discovered that dried eggs were being produced in California and Wisconsin he had them included in the Lend-Lease program arranged by Churchill and Roosevelt. The new food technologies of drying and condensing meant that eggs and milk required far less of the valuable cargo space in those dangerous convoys.

What was not imported was sometimes as important as what was: sugar imports were cut to 19th-century levels, with a corresponding improvement in health that was particularly evident to dentists.

In fact, that was but one measure of what the new British diet achieved. Infant mortality rates were the lowest on record; bone growth and the height of children increased and the rate of every diet-related disease declined dramatically.

So, rather than being starved into submission the British ended the war in robust health. I have always felt that growing up at that time was, in health terms, very lucky. My young body had no opportunity to be seduced by the kind of programmed obesity that afflicts so many kids today.

It should also be noted that in the war more people died of famine than in combat: At least 20 million of famine and 19.5 million in combat. The rate in some countries was horrendous: 2,000 Greeks under Nazi occupation were dying of hunger a day by 1943, and the infant mortality rate rose to 50 percent.

A family picture of the English DRUMMOND family, in 1944 : Sir Jack DRUMOND, 53 years old, director of a biology laboratory at the University of London, his wife Lady Ann DRUMMOND, born WILBRAHAM, 39 years old, and their 2 year old daughter Elizabeth.

Keystone-France/GettyAt the end of the war Drummond was knighted for his work. But his life had a gruesome conclusion.

In the summer of 1952 he set off with his wife and daughter for a driving holiday in France. One evening, when they reached a part of rural Provence, they pulled off the road to spend the night sleeping in their car.

In the morning Sir Jack and his wife were found shot in the car. Their daughter was found nearby, beaten to death with a rifle butt.

Gaston Dominici, a 75-year-old farmer, was arrested and found guilty of the murders. He was sentenced to death but, after three years on death row the sentence was reduced to life imprisonment. He was released in 1960 because of his age and health.

Dominici’s family have always insisted on his innocence. There was no apparent motive. And, as is inevitable with such a distinguished man as the victim, there is a minor industry of conspiracy theorists.

French police at the scene of the murders of British biochemist Sir Jack Drummond (1891 - 1952), his wife Anne and their 10 year-old daughter Elizabeth on a road near the village of Lurs, in the Basses-Alpes department in Southern France, 6th August 1952. The Drummonds were killed on the night of 4th-5th August, while travelling on holiday. Their green Hillman estate car is labelled at top right, as are the spots where each of the three bodies was found.

Keystone/GettyAfter he left government service Drummond joined one of Britain’s leading pharmaceutical companies, Boots, as head of research. One theory has it that the trip to the south of France involved his carrying out some industrial espionage on a French rival, and, having been detected, was assassinated. There is no evidence that Boots ever operated like that, or that Drummond had any talent for espionage.

In France “The Dominici Affair” is now seen as a miscarriage of justice and one of the most tantalizing cold cases of its time.

As for one of Drummond’s curious lasting effects on me, it will always be how special a banana is. He decreed that importing bananas was a needless risk for the ships to undertake since they provided nothing that was not already in his diet. When bananas returned in 1945 they seemed to me like the most exotic fruit in the world, and they still do.