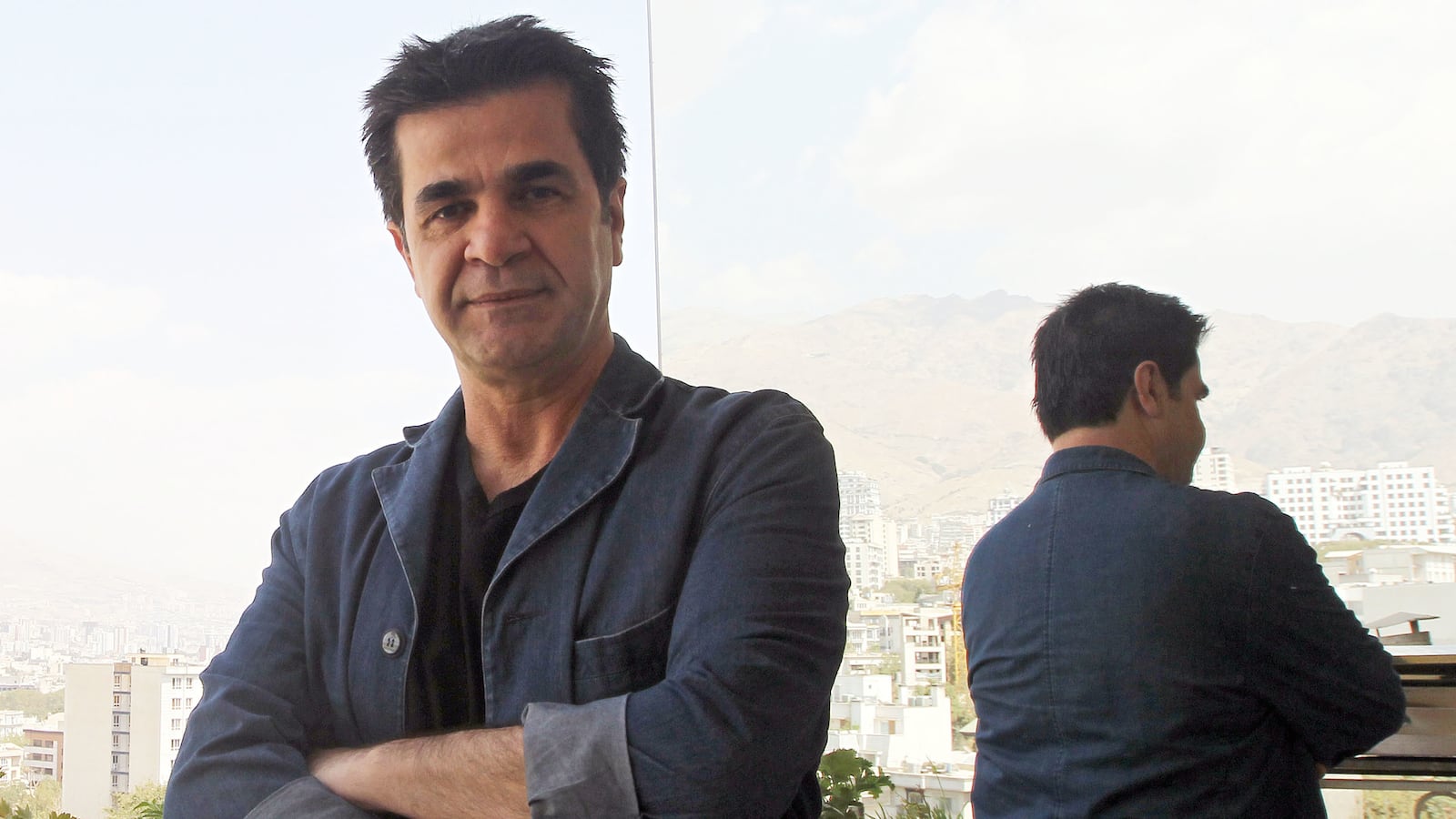

Jafar Panahi’s new film Closed Curtain is an unexpected addition to his remarkable oeuvre. Unexpected not only as another film by a director officially banned from making films, but also as a significant aesthetic departure for him. It marks a startling transition from the familiar social landscapes of the The White Balloon and The Circle to the uncharted labyrinths of the mind.

Panahi was arrested by the Islamic Republic police in 2009 during the clandestine shooting of a film without a government permit. Security agents raided his apartment where the filming was in progress and arrested everyone, including another dissident filmmaker, Mohammad Rasoulof, who was co-directing the ill-fated film about the 2009 failed uprising known as the Green Movement in Iran.

International uproar over the arrest and Panahi’s own hunger strike in jail led to his release after three months, but he was subsequently sentenced to a six-year jail term and a 20-year ban from making films, giving interviews, and traveling abroad. He was slapped with the same phantom charges the government routinely levels against all dissident intellectuals in Iran: acting against national security and spreading anti-government propaganda.

Despite an interview ban for 20 years, Panahi recently talked to me over telephone from Tehran, the megapolis he now calls “my larger prison,” about his aborted film. “It dealt with the consequences of the Green Movement crackdown and how it affected the lives of a family,” said Panahi. “The son is arrested, and his parents clash over how they should react.” Panahi and Rasoulof had shot the majority of the interior scenes and were planning to do the exteriors surreptitiously when they were arrested. All their equipment and the scenes they had shot were confiscated immediately. When I asked Panahi if they were returned to them later, he was surprised that I even asked the question: “You do sound like someone who hasn’t lived in Iran for a very long time!” He reminded me of the plight of another previously jailed dissident filmmaker, Mohammad Nourizad, who has waged a furious campaign, at great risk, to get back his confiscated computer and other personal belongings to no avail.

For the past four years, Panahi has been left in a legal purgatory, known in Iran as the Execution of Verdict. It means he could be sent back to jail at any time at the discretion of the Islamic government. Fearing another backlash, however, the government has refrained from doing so. Keeping him in limbo seems to be the preferred punishment for him in the eyes of the Iranian authorities. They must be hoping despair and uncertainty will eventually dissipate Panahi’s creative energies and render him inactive.

“They freed me from a small jail,” Panahi said, “only to throw me into a larger prison when they banned me from working. It’s not fun to be free but feel like a prisoner. I have to just keep trying to find opportunities to break out from time to time.”

True to his words, Panahi has been bravely defiant. Despite the imposed ban, he has made two “unauthorized” films: This is Not a Film, a subversive wink at the censors, that chronicles a day in his life as a banned filmmaker, and Closed Curtain, a second filmed diary that delves more deeply into his psyche and boldly blurs the lines between the real and the imaginary. The first was shot in the confined spaces of Panahi’s own apartment in Tehran, and the second at his villa on the Caspian coast of Iran.

Panahi has a history of defiance, which explains why most of his films haven’t been shown in his own country. Even when he was allowed to make films the censors would give him a hard time by prescribing “corrections” (a euphemism for cuts) in order to issue screening permits for films like The Circle, Crimson Gold, and Offside. Panahi always objected and didn’t agree to remove “even a single frame” from his films.

His strong resistance against tyranny was not limited to Iran’s borders. In 2000 an ill-conceived American policy of fingerprinting Iranian citizens arriving at U.S. airports prompted Panahi to decline the invitation of his American distributor, Winstar, to promote his film The Circle in the United States. A few months later, however, en route to Mar del Plata Film Festival in Argentina, his flight made a transit stop at New York’s JFK Airport. The customs officials insisted that he submit to fingerprinting before he was allowed to board his connecting flight. Panahi vehemently refused to comply. He later told me he kept repeating “Me artist, no finger” in his broken English. He was arrested, held in chains overnight, and deported back to Hong Kong, where his flight had originated from. Despite the humiliating treatment, Panahi was content that he had not submitted to a law he thought was absurd and discriminatory. “I will react to injustice no matter what the circumstances are. I am not a political person, but as a socially committed filmmaker I have developed a natural tendency to expose injustice and to react to it anytime and anywhere I witness it.”

Filmmakers in Iran are either pro-government or independent. The independents comprise the majority of filmmakers, and although they shy away from making state-sponsored propaganda films, they can’t be identified as anti-government. Dissent is not allowed in the Islamic Republic. Dissident filmmakers are routinely thrown in jail, forced to flee the country, or banned from work. There are prominent filmmakers whose films, as artistically accomplished as they might be, don’t reflect the social conditions in Iran. Panahi, however, refuses to be oblivious to what goes on in his country. He feels his mission as a filmmaker in a crisis-plagued society is “to report to history.”

Panahi is an activist filmmaker whose films are prized achievements of his spirit of defiance. His two most recent films are poignant testimonies to the repression of the arts and the persecution of the artists, not only in Iran, but anywhere in the world where individual liberties are threatened. Panahi thinks one of the most valuable lessons of his incarceration was the realization that he was not alone in his fight. “The tremendous support I received made me realize how united the international community of filmmakers are. It made me feel proud as a filmmaker. I felt I belonged to a global family,” said Panahi.

The limitations have cast a dark shadow over Panahi’s vision. He seems to be increasingly preoccupied with ideas of freedom and confinement in the films he’s done after the imposed ban. “It’s a bit painful to be limited to interior spaces,” said Panahi. He continues, “With the exception of Crimson Gold you rarely see interior scenes in my previous movies. I love to take my camera outside and film the same kind of stories I used to do before the ban. I couldn’t even imagine one day I would be reduced to filming only in my own house and using myself as the main character. But I have no choice. I don’t want to cause problems for other people. Anyone who has worked with me so far has been harassed and barred from leaving the country.”

Despite all the restrictions, Panahi is still fighting, with the same weapons he has always used as a filmmaker: his will, his imagination, and a camera.

Jamsheed Akrami is a film professor at William Paterson University. His new documentary, A Cinema of Discontent, is about film censorship in Iran.

Closed Curtain, directed by Jafar Panahi and Kambozia Partovi, opens July 9th in New York City at the Film Forum, followed by additional markets throughout the country.