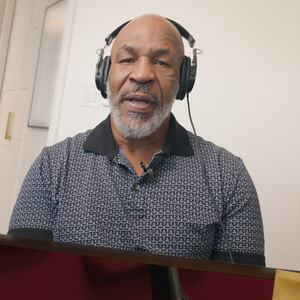

There’s a poetic irony in the coincidence that the most recognizable young boxer in America also has one of the country’s most punchable faces. That face, of course, belongs to YouTube superstar Jake Paul, who announced last week that he will fight 57-year-old Mike Tyson this summer. Actually, Tyson will be 58 when he fights 27-year-old Jake Paul—for reference, Mike Tyson is closer in age to Joe Biden than he is to Jake Paul. This multigenerational match will be carried on Netflix, and in the announcement video, Paul billed the bout as “the biggest fight of the 21st century.”

The problem is that the 21st century has already seen its biggest fight: the 2015 matchup between world champions Floyd Mayweather Jr. and Manny Pacquiao, which made $410 million in the United States with 4.6 million PPV buys. Six years later, when Logan Paul (the elder and more socially acceptable brother) fought Mayweather, the fight generated just over 1 million PPV buys. That’s still a huge number but it couldn’t match the figures for Jake Paul’s fight against wrestler Ben Askren, which reportedly had over 1.5 million buys—making it one of the top-selling fights of the century.

The Tyson-Paul fight will undoubtedly sell a lot of tickets and maybe even a few Netflix subscriptions. But no, Jake Paul is not going to fight the biggest fight of the 21st century against Mike Tyson. And yet you can’t blame him for making that claim. He didn’t invent the gimmick. Boxers have been talking themselves up since Muhammad Ali invented the routine. And you can’t blame legitimate, gray-haired fighters for stepping into the ring with YouTube superstars. The paydays are absurd. Mayweather boasted that he made $30 million from the advertisements on his trunks alone, quipping, “Your kids can’t eat legacy.”

Mayweather was not hurting for cash before his fight with Logan Paul, but he draws a notable line here between legacy and money. And Jake Paul’s mission seems to be to blur that line as much as possible. This mission has been particularly painful for the UFC as Jake Paul has taken the league’s over-the-hill champions like Nate Diaz and Anderson Silva into the ring and made a mockery of their belts. Sure, they’re old, they’re not boxers—but it’s still pretty disenchanting to see them lose to a kid who boxes like he picked it up on Nintendo Wii.

UFC owner Dana White understands the monetary motivation of his champions stepping into the ring with Jake Paul. But White does so through gritted teeth and with plenty of caveats. After the Diaz-Paul fight, Dana White was quick to point out that Paul was the much bigger fighter and that Diaz was “pushing 40.” During a 2022 press conference, when the UFC owner was asked about the Silva-Paul fight, he cut off the question and shot back, “Stop asking me about Jake Paul, you guys. I don’t give a shit what Jake Paul does… the guy has nothing to do with my business. Nothing to do with my business.”

But then again, what is Dana White’s business? He brings fighters up through a reality television show. He sells fights on pay-per-view television. The most valuable fights are those with big names, big personas like Conor McGregor and Colby Covington. UFC fighters frequently adopt similar antics to Jake Paul in order to amplify their name-recognition and get bigger fights. Whether he likes it or not, Dana White and Jake Paul are in the same business. Jake Paul has simply removed the sheen of sport from that business and developed it into its basest form—a reality television charade.

It’s hard to feel bad for anybody in this story. Like Jake Paul, Dana White is famously easy to despise. But what about the fighters? Mike Tyson is a complicated figure outside of boxing. His legacy is as much about the face tattoo and the prison time and the light cannibalism as it is about his boxing. And Canelo Álvarez? For those unaware, Álvarez is a consistently exciting Mexican boxer with world championships in four weight classes. He’s one of the best boxers in the world, and Jake Paul is obsessed, absolutely obsessed, with fighting him. In 2022, when Álvarez was asked about a potential match-up with Paul, he agonizingly pumped his palm into his face before responding, “Why are you guys asking me for that—especially that fight? Jake Paul? Please, guys.”

This is where Jake Paul has blurred the line. Jake Paul is an entertainer and Álvarez is a sportsman. These men should not be in the same conversation, and yet they regularly are. You don’t feel bad for Dana White when he’s asked about Jake Paul but you do feel bad for athletes like Álvarez. Imagine if Patrick Mahomes was constantly compared to the starting quarterback in the puppy bowl. And furthermore, imagine if reporters and podcasting clout-chasers were constantly badgering Mahomes about why he won’t play against the reigning puppy bowl champions.

Mahomes enjoyed his ride into cultural ubiquity thanks in part to Taylor Swift’s romance with his teammate. Swift brought millions of viewers to the NFL. And the counterargument for Jake Paul sounds similar to the pro-Swift NFL argument: Paul’s defenders say he’s bringing new fans into the sport. They say he brought visibility to fighters like Regis Prograis, who was a co-main event on the Paul-Askren card, which again, brought in 1.5 million PPV buys. Millions of people watched Prograis win that fight. But a year later, when Prograis fought for a world title, the fight earned a paltry 20,000 PPV buys. So much for new fans.

I don’t mean to go back to Taylor Swift (this is 2024, everything eventually leads back to Taylor Swift) but Taylor Swift did not change the game of football in her image. Sure, she brought it more visibility, she ushered in a new fan base. But she wasn’t on the field in the same way that Jake Paul is in the ring. Jake Paul isn’t bringing in a new fan base. He’s changing the sport of boxing in America.

Gone are the days of boxing superfights like the Rumble in the Jungle or the Thrilla in Manila. Most of the top-selling (and most-watched) boxing matches of the 2020s are likely to be Jake Paul boxing matches. The sideshow is now the main event. Paul is turning the sport into a novelty. And he’s doing it one aging fighter at a time.