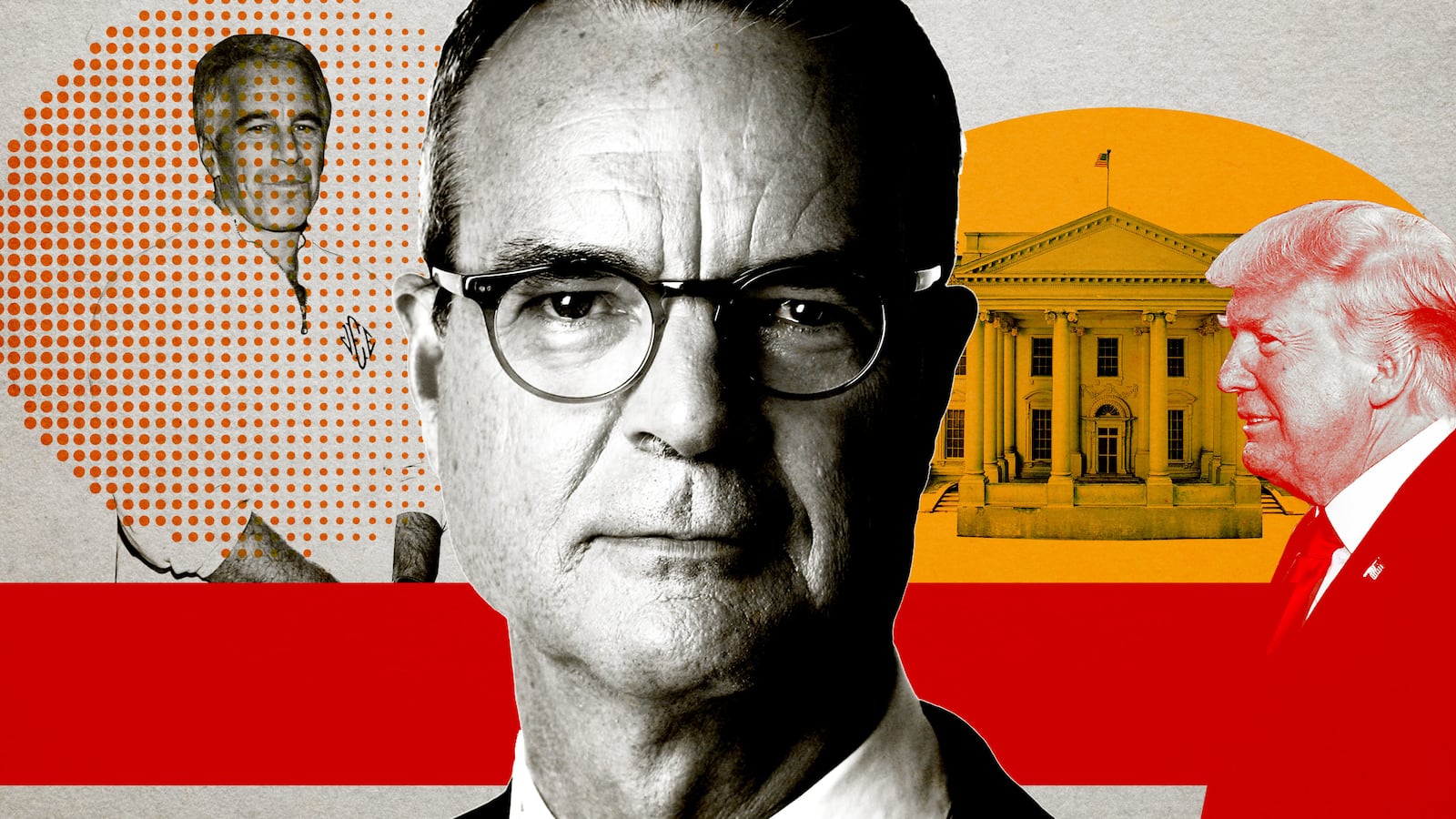

Early in his career covering the financial industry, law enforcement, and the unsightly pageant of American politics, Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist James B. Stewart spent quality time with both Hillary Clinton during her husband’s first term in the 1990s and Donald Trump in the late 1980s.

One was an activist first lady who, like Bill Clinton, was bitterly resentful of media scrutiny and had hoped to enlist Stewart—a bestselling author whose just-published 10th book is Deep State: Trump, The FBI, and The Rule of Law—to expose the rank unfairness of the press coverage of the Clintons and certify their probity and honesty.

The other was an outer-borough apartment-building scion who was trying to recast himself as a high-flying corporate raider and wanted Stewart, then a Wall Street Journal reporter, to validate his status and acumen.

Neither the Clintons nor Trump succeeded.

“He invited me up to Trump Tower and said, ‘This is completely off the record, deep background,’” Stewart told The Daily Beast. “And then we’re sitting there and the secretary walked in and said ‘Mrs. So-and-So is here.’ And Trump says, ‘Show her in’—so much for being deep background, off-the-record. And so she walked in and he said, ‘This is Mrs. So-and-So’—I don’t remember her name, but she was from the Philippines—‘and she is the richest woman in the world.’ And I thought, ‘Ohhh, interesting, I never heard of her. I thought the Queen was the richest woman in the world.’

“And then he turned to her and said, ‘James Stewart from The Wall Street Journal is here interviewing me. He is the most famous reporter in America.’ At which point I knew she was not the richest woman in the world,” Stewart recalled, adding he found the future president “charming and funny in kind of a mean way,” but that he politely declined Trump’s offers of a free flight on the Trump Shuttle, his money-losing airline that was soon to go under, a ride to La Guardia airport in his limo, and, later on, persistent invitations to prize fights in Atlantic City.

“He was always trying to get me to take something,” Stewart said. “Fortunately, I had no interest in boxing. I had no interest in gambling.”

The dapperly dressed Stewart, who happened to be celebrating his 68th birthday, was holding forth in a midtown Manhattan coffee emporium across the street from The New York Times, where he has been a star for the Business section since 2011.

He said he was currently toiling on an investigative report concerning the late Jeffrey Epstein, the plutocrat-pedophile whom Stewart visited at his Upper East Side mansion in August 2018. Stewart refused to provide details on his research or when he hopes to publish—although it could be soon.

“It’s at a delicate stage,” he said.

In August, after Epstein was found hanged in his jail cell, apparently by his own hand, Stewart wrote a controversial column about their off-the-record encounter.

The column raised eyebrows about Stewart’s apparently cordial interaction with the notorious registered sex offender, who had pled guilty in 2008 to procuring an underage prostitute in Florida, and had served a very light prison sentence under a non-prosecution agreement negotiated by his high-powered legal team.

Stewart’s column also raised questions about why the New York Times didn’t pursue an investigation of the socially well-connected sex offender in their own backyard prior to his arrest at New Jersey’s Teterboro airport—on July 6, 2019, nearly a year after Stewart’s visit—on new federal charges of sex trafficking.

In his column Stewart explained that he’d met with Epstein because he was trying to ascertain if rumors were true that Tesla tycoon Elon Musk had asked Epstein to represent him in his search for new members of the Tesla corporate board, and concluded that there was no credible evidence for that.

The Times also assigned longtime business reporter Landon Thomas Jr., who 10 years earlier had written with strange empathy about Epstein during the criminal proceedings in Florida, to interview him concerning his supposed relationship with Musk and Tesla. Thomas did the interview, although no news story resulted.

But the assignment later proved a major embarrassment for the newspaper when NPR revealed, shortly after Stewart’s column appeared, that Thomas and Epstein were friends and the reporter had successfully solicited a $30,000 charitable donation from the financier for a school in Harlem. (When Thomas came clean with his editors, The Times forbade him from having further contact with Epstein, and he left the paper early this year.)

During his sit-down with Epstein, Stewart quickly determined that he would not be a solid source. “I thought he was slippery and evasive,” he told Columbia Journalism Review Editor in Chief Kyle Pope shortly after his column was published.“I don’t like dealing with people like that as a source.”

Given Epstein’s criminal past, Stewart said he was surprised that when he arrived at his East 71st Street residence, “a beautiful young woman opens the door—I was kind of taken aback by that. If it was me, I would not have had a young woman at the door to make the first impression for somebody coming there.”

Stewart added that while he thought the woman was young, he didn’t consider her underage. “If I had to guess, I would say 19, 20, 21, something like that,” he told Pope.

When Epstein sat down with him for their chat, Stewart said, he considered it a strange form of “rapport-building” when Epstein insisted on discussing his legal troubles and his attraction to young women and girls.

“It was kind of the elephant in the room. I knew he was a fairly notorious character” but in the end “I was indifferent. I was there to find out what if anything he knew about the Musk situation,” Stewart said. “Frankly, he threw a lot of people under the bus in that interview. He talked about their sex activities and their drug use…I don’t even know if it’s true, but he was dropping names left and right…mostly to show me how plugged-in he was…He was utterly unapologetic about his behavior. He did not show a trace of remorse. There was no contrition whatsoever.”

Stewart told Pope that soon after his August 2018 interview, he discussed with his editor the possibility of doing a piece about Epstein’s efforts to return to polite society and the prominent people who were enabling him, ” but “there were a zillion other things going on. It never happened. Then when he got re-arrested, I got involved in the story” but didn’t consider using material from his previous encounter because of the ground rules—which were no longer applicable after Epstein’s death, Stewart said.

As for critics who said Stewart should have violated the ground rules immediately after his Epstein interview “because he was involved in some kind of crime,” Stewart said: “That strikes me as totally off-base. First of all, he’s already pleaded guilty and served his time. I didn’t think the woman [at the door] was underage, and I assumed, maybe naively, that once you’re on probation or whatever he was, you’re going to be very careful to obey the law and not do anything.”

Stewart wrote in his column that he declined Epstein’s offer to cooperate with a book-length biography, and also spurned Epstein’s invitation to have dinner with him and Woody Allen.

Stewart told The Daily Beast that such an encounter would have been journalistically useless, to say nothing of the unattractive optics.

“How creepy is that?” he scoffed.

In an email on Tuesday, Stewart addressed a series of questions about the Epstein episode, including whether the Times should have followed up last year on investigating Epstein’s possible continuing criminal misconduct, and whether Stewart should have written contemporaneously about the Woody Allen dinner invitation and Epstein’s apparent friendship with an accused sex offender (although Allen was never criminally charged and has consistently proclaimed his innocence).

“I believe my editors at the Times handled my visit with Epstein professionally and appropriately,” Stewart wrote in his email. “I had no reason to believe that Epstein was violating any provisions of his sentence or had continued to engage in any unlawful conduct. I never entertained the possibility of having dinner with him and Woody Allen (or anyone else), but neither did I consider such an invitation newsworthy. Since his arrest last summer, I've been focused on reporting the Epstein story wherever it leads, with the full support of my editors.”

Stewart won’t say precisely who cooperated with his latest book, beyond on-the-record interviews with fired FBI Director James Comey and, surprisingly, Steve Bannon—who makes a cameo appearance to mock the “deep state” conspiracy theory, embraced by Trump, that a cabal of faceless government bureaucrats are staging a secret coup against the duly elected president.

The “deep state conspiracy theory is for nut cases,” Stewart approvingly quotes Bannon. “America isn’t Turkey or Egypt,” Bannon says, adding that while there’s an entrenched bureaucracy, “there’s nothing ‘deep’ about it. It’s right in your face.”

Comey, meanwhile, tells Stewart: “There’s no ‘deep state’ looking to bring down elected officials and political leaders that represents a deep-seated center of power… But it’s true in a way that should cause Americans to sleep better at night. There’s a culture in the military, in the intelligence agencies, and in law enforcement that’s rooted in the rule of law and reverence for the Constitution.”

A careful reading of Deep State suggests that Stewart managed to secure the cooperation of Comey’s fired interim successor, former Acting FBI Director Andrew McCabe (who wrote his own book about recent events) and former FBI in-house counsel Lisa Page and top agent Peter Strzok, the so-called “gaga lovers,” per Trump’s toxic Twitter feed.

Page and Strzok lost their jobs after the public release of text messages in which the two, who were married to other people, not only indicated they’d been having an affair, but were insulting and critical of the former reality-television star who went on to become the 45th president.

“America depends on institutions,” Stewart said about the overarching theme of Deep State. “And it depends on people functioning in those institutions whose first loyalty is to the Constitution and the rule of law—not to an individual who may happen to be president at one time or another. I want people to understand that and respect the fact when people act on behalf of the interests of the Constitution and the American people, it’s not an act of betrayal. It’s the highest form of patriotism.”

A few years after that Trump Tower meeting, during Bill Clinton’s first term as the 42nd president, Hillary’s close friend Susan Thomases, then a securities lawyer and managing partner at the blue-chip law firm Willkie Farr & Gallagher, arranged a meeting between Stewart and the first couple at the White House.

“They initiated my book,” Stewart said, referring to Blood Sport, his 1997 bestseller that chronicled the pre-Monica Lewinsky scandals, which included the conspiracy-theory-inducing suicide of deputy White House counsel and Hillary intimate Vince Foster. “They sent an emissary [Thomases] to me saying, ‘We’re being persecuted by the press,’ and she said, ‘They want you to do a book and they have nothing to hide. They’ll show you everything.’

“So I went to the White House and met them—Bill was delayed, delayed, delayed, and finally popped in to say hi—and I spent most of the time with Hillary… They were supposed to be interviewing me. But Hillary did all the talking. ‘We’re being persecuted. The media’s so unfair. We have nothing to hide.’

“And I chimed in and said, ‘I hope that’s true, because I’m going to do my usual thorough job, and once I go down this path and sign a deal, this is my livelihood, there’s no turning back.’ And she said, ‘Oh yeah, we understand that. That’s fine.’ That was the high-water mark of our relationship.”

When the Clintons failed to provide promised documents and canceled scheduled interviews, Stewart decamped to Little Rock, Arkansas, “and everybody was eager to talk,” he recalled. “And somehow word got back to the White House that I spoke to the state troopers [who were members of Bill Clinton’s security detail when he was Arkansas governor]. I did talk to the troopers. I was talking to everybody, and boy, did I get an earful.”

Stewart soon had the strange feeling that his movements in Little Rock were being monitored by a local network of Clinton loyalists. “Every time I came out of my hotel, I think somebody reported back to the White House. I later heard that the minute they [the Clintons] heard I talked to the troopers, it was over. And they never spoke to me again.”

Decades later, Trump and the Clintons are central figures in Stewart’s latest book, from which neither party emerges unscathed.

On the other hand, Comey, whom Stewart has known and reported on since Comey’s days as U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York, comes across as something of a hero—albeit a flawed one—who risked his career and reputation in order to resist Trump’s misuse of presidential power.

“I knew Comey and held him in very high regard. Comey tells the truth. I have never known him to lie,” said Stewart, a non-practicing attorney who graduated from Harvard Law School and spent a few years as an associate at Cravath, Swaine & Moore before returning to his first love, journalism. He was a summer intern at his small-town Illinois newspaper, the Quincy Herald-Whig, and also worked on the undergraduate newspaper at Indiana’s DePauw University.

In the end, Deep State is “a thriller, full of intrigue and drama,” as Stewart puts it, featuring a mendacious, bullying president driven by ego and self-interest, his hand-picked enablers in government, and diligent public servants and denizens of the “deep state” like Comey and his interim successor McCabe—and even Page and Strzok—who attempted, with limited success, to foil Trump’s efforts to subvert the Constitution.

Although Stewart was compelled to finish Deep State months before the latest White House horror—namely the formal impeachment inquiry prompted by Trump’s apparent attempt to get Ukraine to investigate political rival Joe Biden in return for military aid—Stewart argued it’s not a problem.

“All the behavior that Trump has now exhibited is amply dramatized in my book,” he said. “He’s impulsive. He doesn’t listen to people giving him advice—even more so now. The minute he’s caught red-handed, he immediately—in Roy Cohn fashion—turns the attack on the people who are criticizing him. If you reveal embarrassing behavior by him, you’re a quote-unquote traitor, with the implication that you should be given some kind of death penalty. And he lies constantly. Constantly. All that behavior is here.”

In Deep State, meanwhile, Stewart provides the most detailed—and damning—account to date of Bill Clinton’s ill-considered June 27, 2016, visit with Attorney General Loretta Lynch on a Justice Department jet parked in Phoenix. Amazingly, this occurred during the FBI’s ongoing investigation of Hillary’s mishandling of classified emails as secretary of state, a probe that was threatening to derail her presidential campaign.

Ever loquacious—after Lynch welcomed him aboard against her better judgment—the former president ignored the AG’s repeated protests that she had to go, took a seat in the cabin and talked her ear off about the Arizona heat, Brexit, globalization, West Virginia coal miners, and other weird topics.

“That Bill Clinton would be so tone-deaf as to initiate an extended private conversation with the attorney general, the very person weighing criminal charges against his wife, just five days before her FBI interview astonished Lynch’s staff,” Stewart writes.

Stewart told The Daily Beast: “Oh my God, Clinton! I’m sure it’s subconscious… The person with him said, ‘I don’t think it’s such a good idea,’ and yet he bludgeons his way up there, plops down, lingers for such a long period of time that it made everyone question, ‘What the hell are they talking about?’ Was he trying to undermine his wife? That’s crazy! He couldn’t have done a better job. It was a disaster for her.”

Arguably, however, the person who comes out worst of all is Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein—who was widely portrayed in the press as “honorable” and “a straight-shooter” when Attorney General Jeff Sessions recused himself from the Russia investigation and Rosenstein appointed former FBI Director Robert Mueller as special counsel.

“Look, he was in an impossible situation. What should he have done in his position?” Stewart said, citing the notorious memo Trump ordered Rosenstein to write as the justification for sacking Comey—i.e., that the FBI director had overstepped his authority and violated Justice Department policy in the bureau’s investigation of Hillary Clinton’s email scandal.

“I guess if it was me, I would have resigned the day of [Trump’s] phony story that ‘The reason I’m firing Comey is because of the way he dealt with the Clintons,’” Stewart continued. “What happened to Rosenstein the following week? Obviously he was deeply upset and bouncing off the walls and coming up with these wild ideas”—notably Rosenstein’s suggestion that Cabinet officials be persuaded to invoke the 25th Amendment to remove Trump as president, and his offer to wear a wire into the Oval Office to catch the president saying something incriminating.

In neither case was Rosenstein joking, Stewart’s books recounts—contradicting Rosenstein’s spin that he was merely being “sarcastic.”

“He was coming unglued. By the way, there are many witnesses to this,” Stewart pointed out.

In Deep State, Stewart quotes Comey, after Trump nominated Rosenstein to be the Justice Department’s No. 2, as musing prophetically to his friend Benjamin Wittes that Rosenstein was essentially “a survivor” who might compromise his principles to keep his job.

“And, oh my God, does that turn out to be true,” Stewart told The Daily Beast. “There were two occasions when people were writing the stories that Rosenstein was going to be fired”—after Rosenstein’s “wild ideas” were widely reported. “He goes in for a one-on-one with Trump and miraculously he comes out with his job intact.”

Noting that Rosenstein was Mueller’s boss, Stewart said that if Mueller had agreed to speak to him for the book—which he didn’t—“there are two questions I wanted to ask him. One is, why isn’t Rosenstein in the Mueller Report except in passing? None of that stuff about the week after [Comey’s firing] is in there. Everybody I interviewed was interviewed by Mueller, so I know he knows the whole story. So Rosenstein was mysteriously spared in the Mueller Report.”

Stewart’s second question: “Why didn’t Mueller insist on testimony from Trump specifically on obstruction of justice? Because he allowed Trump to refuse to testify about obstruction. No prosecutor I know would accept a deal like that. There are communications between Mueller and Rosenstein and Rosenstein and Trump that I don’t know. All I know is that whatever Rosenstein said to Trump, he kept his job.”

Stewart speculated that because the president was keenly aware that Rosenstein had recommended removing him from office and offered to wear a wire to gather evidence against him. “It’s inconceivable that Trump would have kept him on if he wasn’t able to use that leverage to get something in return. Again, I’m not privy to those conversations. But if I was a fly on the wall, the one thing I would have loved to have heard is the back and forth between the two of them.”