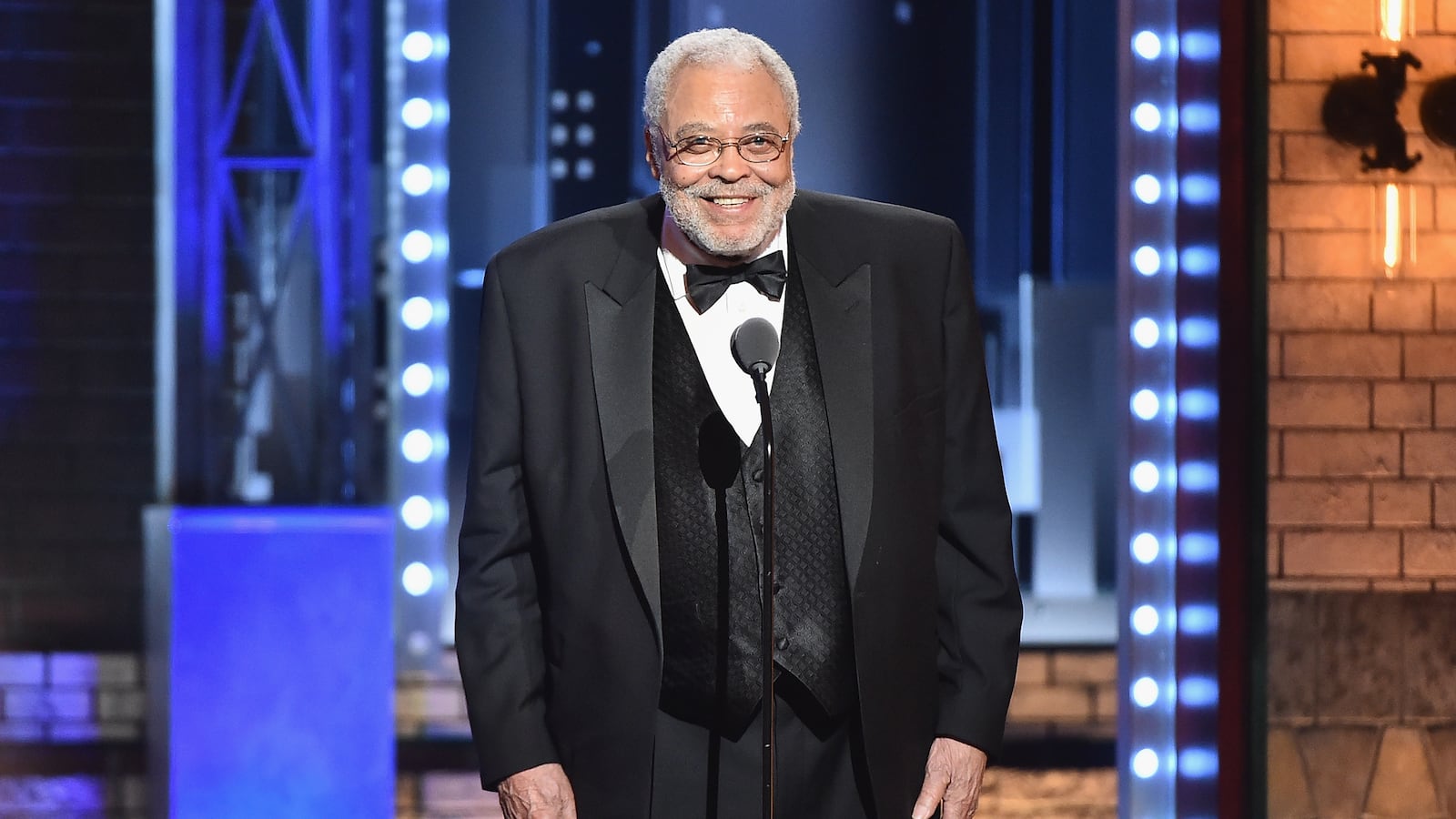

James Earl Jones, one of the greatest actors of his generation, whose uniquely resonant and authoritative bass-baritone voice undergirded his undeniable gravitas as a performer, died on Monday morning. He was 93.

His representatives at Independent Artist Group confirmed his death to the Daily Beast in a statement, saying he’d died surrounded by family at his home in Dutchess County, New York. A cause was not immediately shared.

Deadline was the first to report the news of his death.

After overcoming a debilitating stutter as a child, Jones was already a veteran stage actor by the time he made his onscreen debut at the age of 32 as the bombardier in Stanley Kubrick’s 1964 Cold War satire Dr. Strangelove.

His role as Lt. Lothar Zogg had been slashed to ribbons by the time he arrived on set, reduced on the page from a “voice of reason” challenging his superiors down to a single, tremulous question, he recalled in an essay for The Wall Street Journal in 2004.

James Earl Jones & Darth Vader during Star Wars: Episode II - Attack of the Clones Charity Premiere in New York City

Jim Spellman/WireImage via Getty ImagesStill, “I felt very fortunate to be working with Kubrick, one of the most brilliant and innovative directors of our time,” Jones wrote. “He was unique—the only man I have ever known who spoke in the manner, if not the accent, of an English lord and chewed gum at the same time.”

Over the next six decades, Jones would amass a multitude of credits across films like Claudine (1964), for which he was received a Golden Globe nomination, as well as Coming to America (1988), Field of Dreams (1989), The Hunt for Red October (1990), and The Sandlot (1993).

Subsequent generations of audiences primarily came to know him through his voice work, particularly as Darth Vader in the Star Wars franchise and, later, as Mufasa in The Lion King.

He ended up in the first Star Wars film during the post-production process, he explained in Empire of Dreams, a documentary about the original trilogy.

“George had hired David Prowse [to play Vader], but he said he wanted a so-called ‘darker’ voice,” Jones said. “Not in terms of ethnic, but in terms of timbre. And the rumor is that he thought of Orson Welles.

“But he probably thought that Orson might be too recognizable, so what he ends up doing is picking a voice that was born in Mississippi, raised in Michigan, and was a stutterer. And that happened to be my voice.”

James Earl Jones in the titular role of Joseph Papp's New York Shakespeare Festival production of 'King Lear' in Central Park, New York, July 1973.

Jack Mitchell/Getty ImagesJones recorded all his lines in just one day, was paid $7,000, and was not listed in the credits of the film when it hit theaters in 1977. “I lucked out,” he told the American Film Institute in 2009.

Always with a dignified nod to his popcorn-blockbuster roles, Jones occasionally expressed lighthearted exasperation that he was not more well-known for his classical work.

“I’ve done a King Lear, too! Do the kids know that? No, they have the Darth Vader poster to sign,” he despaired to Broadway.com in 2010. “But it’s OK. When you appear before an audience, you learn to accept whatever they give you. Hopefully they give you their ears, as Antony said.”

Born in 1931, Jones went east to New York City in 1957 to follow in the footsteps of his father, Robert Earl Jones, who had abandoned his family before his son’s birth to be an actor.

The elder Jones found early work with the playwright Langston Hughes and would go on to appear in more than 20 movies, including as an aging con artist in the Oscar-winning 1973 caper flick The Sting.

James Earl Jones as Othello and Christopher Plummer as Iago in Shakespeare's 'Othello', 1981.

Afro American Newspapers/Gado/Getty ImagesThough The New York Times reported upon his death in 2006 that Robert had reconciled with his son in the mid-1950s, they were never truly close, according to James.

“He had nothing to do with my life, really because there was a separation between my mother and him,” Jones told CBS News in 2014. “Even between my mother and my grandmother. I was raised by my grandparents.”

Jones’ grandparents moved him from his birthplace of Mississippi to Michigan at the age of 5, a sudden change that destabilized the boy and left him with a distinctive stutter. He began to overcome it in high school, when a kindly English teach “discovered I wrote poetry, secretly, and he said, ‘If you like words that much, James, you ought to be able to say them out loud,’” he remembered.

Performing Shakespeare’s poetry eased the issue—“If I hadn’t been a stutterer, I would never have been an actor,” he said—but Jones continued to wrangle with his stammer for the rest of his life.

“I’m a stutterer, and I’m happy that anything comes out at all with clarity,” he told Conan O’Brien in 1995.

James Earl Jones looking at his reflection in a mirror in a dressing room before going on stage to appear in the play 'The Great White Hope' on Broadway, 10th December 1968.

Harry Benson/Daily Express/Getty ImagesIn New York, he appeared both on and off-Broadway before finding an artistic home at Joe Papp’s New York Shakespeare Festival, where he played the title roles in King Lear and Othello.

Reacting to his 1964 Central Park performance as the Moor, the Times noted that Jones “commands a full, resonant voice and a supple body, and his jealous rages and frothing frenzy have not only size but also emotional credibility.” Jones would fall in love with and wed his Desdemona from that production, Julianne Marie. They would divorce in 1972.

On the Great White Way, Jones picked up Tony Awards for his turns as a tortured boxer in Howard Sackler’s The Great White Hope in 1968 and August Wilson’s Fences in 1987. (His last Broadway performance was in a 2015 revival of The Gin Game.)

Jones would go on to reprise his role as the prizefighter Jack Jefferson, based on real life champion Jack Johnson, in the 1970 film adaptation of Sackler’s play. He was nominated for an Oscar for the performance, but lost to Patton’s George C. Scott—his co-star from Dr. Strangelove, who happened to be the reason that Kubrick first took notice of Jones.

“When Stanley came to New York to scout George C. Scott for the role of the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, George happened to be playing in The Merchant of Venice at the Delacorte Theater in Central Park,” Jones wrote in the Journal. “So was I. Stanley recruited George, and given that Kubrick wanted to make the film’s B-52 crew multiethnic, he took me too.”

Legendary American actor James Earl Jones poses with his "Lifetime Achievement" Oscar that he received from Sir Ben Kinsley after his performance in "Driving Miss Daisy" on November 12, 2011.

Dave M. Benett/Getty ImagesJones never won a competitive Oscar. He was, however, presented with an honorary statuette in 2011 by Sir Ben Kingsley.

“You cannot be an actor like I am and not have been in some of the worst movies like I have,” Jones said onstage. “But I stand before you deeply honored, mighty grateful and just plain gobsmacked.”

His final film appearance came in 2021, when he reprised his role as Eddie Murphy’s royal father in Coming 2 America.

He was married twice, to Marie and actress Cecilia Hart. Hart and Jones met starring in the short-lived CBS police procedural Paris, and they would wed in 1982, shortly after she was cast as another Desdemona opposite one of his Othellos. They would remain married until her death in 2016.

She and Jones are survived by a son, Flynn Earl Jones. Jones is also survived by Marie and a brother, Matthew.