This week the Tokyo Metropolitan Police Department's (TMPD) organized crime control division set up a special task force of 50 police officers to obliterate the yakuza from the entertainment industry. They’ll have their work cut out for them.

The crackdown began in August when Japan’s most ubiquitous television host and comedian, Shinsuke Shimada, “the Jay Leno of Japan,” was fired by his talent agency, Yoshimoto Kogyo. Undeniable evidence of the star’s personal and business dealings with the Yamaguchi-gumi, Japan’s largest crime group, had come to light. Shimada was so popular in Japan that he hosted six different television programs before his fall from grace. On Aug. 31, the TMPD began questioning Shimada’s former employers about his ties to the yakuza and the company’s own corporate compliance with anti-organized crime national laws and its readiness for the new Tokyo organized crime exclusionary ordinances which go into effect in October.

But Shimada is only one of many celebrities with yakuza ties. In the last few weeks, extensive evidence has emerged that Japanese show business is saturated with the yakuza’s influence. Police records and sources, along with testimony from current and former yakuza members, have revealed that many powerful Japanese talent agencies and production companies are not simply fronts for the yakuza—they are the yakuza.

For instance, Rikiya Yasuoka, a Japanese movie star, was allegedly once a member of an organized crime group, and attended and sang at a birthday party for the former don of Japan’s entertainment business, Tadamasa Goto, the “John Gotti of Japan.” The police view him as a yakuza associate. Goto has re-emerged as a yakuza boss with a new gang, the hyperviolent Kyushu Seido-kai, and the unveiling of the Shinsuke Shimada scandal appears to be his attempt to once again get a foothold in show business. On Oct. 1, new laws go into effect that criminalize providing aid or pay-offs to organized crime. Many entertainment firms are in serious danger of being officially designated yakuza front companies, having executives arrested and publicly exposed. Some talent agencies, such as the well-known and extremely powerful Burning Productions, have been recognized by police as organized-crime front companies since 2007.

Japan’s entertainment industry has long been dominated by the yakuza. Yamaguchi-gumi members interviewed for this story have pointed out that the relationship between the talent agency Yoshimoto Kogyo and their organization has existed for decades, even going so far as to say, “Yoshimoto Kogyo isn’t a front company of the Yamaguchi-gumi, it is a branch of the Yamaguchi-gumi.”

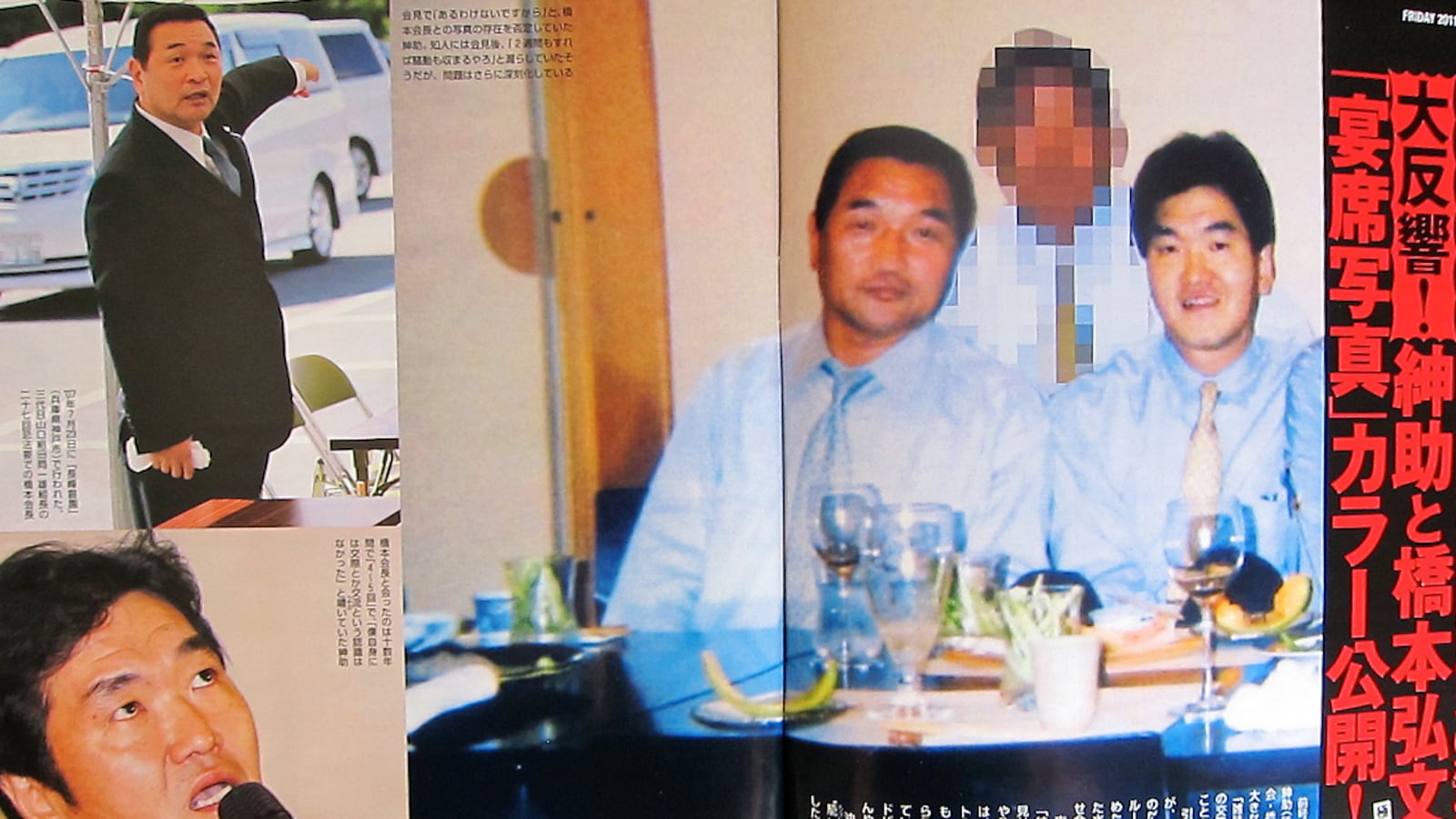

Shimada Shinsuke’s ties to organized crime were well-known long before conclusive evidence forced Yoshimoto Kogyo to fire him, although they let him stage it as a resignation out of respect for his past contributions to the company. The police have known of the close ties between the yakuza and Shimada since 2005. A former Osaka police department detective said, “Shimada Shinsuke is a yakuza in celebrity clothing. Photos taken of him with Chairman Hashimoto, the fourth most powerful leader of the Yamaguchi-gumi, were seized in a 2005 raid of Hashimoto’s office as well as damning documents.” The press has known of the tight relations between the two since 2006.

It was in 2005 that Shinsuke Shimada became close to Chairman Hashimoto. Shinsuke, while in Osaka, had an angry encounter with a right-wing group in which he compared the emperor’s imperial crest to his anus. He then denigrated the right wing on an Osaka television program, alienating several right-wing groups, which began protesting in front of his home and office, threatening him with death. He turned to his friend, ex-boxer and Yamaguchi-gumi member Jiro Watanabe, for help. Watanabe contacted Hashimoto, who convinced the right-wing groups to keep quiet. In return for the favor, Shimada delivered over ¥11 million ($1.7 million) to Hashimoto. This was the beginning of a long friendship detailed in over 106 emails, dating from 2005 to 2007.

Hashimoto also visited one of Shimada’s bars with his lackeys, paying for the evening with a stack of ¥10,000 bills, neatly wrapped in a bow, totaling 20,000,000 yen ($26,000). Needless to say, that amount was much more than the actual bill. The two began working together on real-estate deals as well.

In 2009, Tadamasa Goto, the former Yamaguchi-gumi gang boss, wrote extensively in his autobiography, Habakarinagara, of his connections to Japan’s entertainment industry, and justifies the attack his members made on a famous Japanese film director, Juzo Itami, who dared to depict the yakuza unfavorably in his dark comedy The Gentle Art of Japanese Extortion. Goto also publicly derided Shimada, calling him a hypocrite and a “chinpira” -- yakuza slang for the lowest-ranking member or a yakuza that does not honor the codes of the organization. “Calling Shimada ‘a little chinpira’ was a subtle way of outing him as a yakuza,” say police sources. “Everyone in law enforcement who read that passage knew exactly what he meant.”

On March 15 of this year, Takarajima, the publisher’s of Goto’s book, released a paperback with a chapter devoted to Shinsuke Shimada connections to the Yamaguchi-gumi. Shimada was summoned by Yoshimoto Kogyo officials and questioned about the allegations but dismissed it as “sour grapes from a loser ex-gangster.” At one time, Shimada and Goto had been close friends.

The industry’s ties to the crime gang go on. Japan’s most famous director, Takeshi Kitano, who is well known for his romanticized movies about the yakuza, even did an interview with Seijro Inagawa, the supreme leader of the Inagawa-kai, for the monthly magazine Shincho 45 in 2002. (The Inagawa-kai, based in Tokyo with offices across from the Ritz-Carlton Tokyo, is the third-largest organized crime group in Japan with roughly 10,000 members.) For a yakuza, Seijo Inagawa was well respected in Japanese society. When he would ride a plane, he would tip flight attendants the equivalent of $3,000 each. He was known to give money to local businesses and not ask for repayment. And he was very strict about keeping discipline within the ranks. When Japan’s legislature, the Diet, was in the process of creating the first anti-organized crime laws in 1991, many members of the Inagawa-kai wanted to fight the law in court, but Seijo Inagawa would have no part of it. In a meeting of his top executives, he told them, “This law is going into effect because we have all behaved badly. We have bothered ordinary citizens, departed from our code, and this law is a result of that. Behave yourselves and obey the law.”

Kitano, for his part, has made several films about the yakuza and he knows his subject matter well. In his book Kitano Par Kitano, published last year, Kitano discusses “the dark powers” of Japan and notes, “Japan has two governments. One is the public government. The other is the one that issues orders to public institutions, the hidden government. In Japan, in every profession, almost without exception, there is the yakuza or something akin to the yakuza in the background. They’re kind of like a secret police and to succeed in business there are many cases where they’re needed. Amongst past prime ministers, there were individuals who quietly used them. The areas of television, show business, sports—they’re not an exception.”

He goes on to lament that in recent years, due to internal struggles within the Inagawa-kai, there are now many members who no longer uphold the group’s code of ethics. Police sources say that Kitano has had not ties or social relations with the yakuza in any form since 2005.

Yakuza funerals and birthday parties are celebrity events. In photos from the wake for the third-generation leader of the Inagawakai, Yuko Inagawa, in May 2005, you can see flowers that were sent from Office Kitano, which is Takeshi Kitano’s management company, and several famous Japanese entertainers and talent agencies.

Office Kitano (株式会社オフィス北野), the firm that manages affairs for Takeshi Kitano, replied to enquires on September 12 by noting, “The flowers were sent because Inagawa-san had cooperated in doing an interview with Mr. Kitano, and the representative of our office sent them as a courtesy. In Japan, when you have worked together with someone, and someone close to them dies, to send funeral flowers (供花) is a custom.” Kitano has had no regular contact or associations with the Inagawa-kai or organized crime members other than the interview and the sending of flowers.

In an interview in the most recent issue of Shunkan Bunshun, after I had queried his office about his current and past relations to the yakuza, Kitano harshly criticized Shimada, breaking a taboo amongst the celebrity community not to discuss the issue. He notes, “I’m different from Shinsuke; I’d never ask the yakuza for intervention. Asking the yakuza to get things for him, that’s where he (Shinsuke Shimada) really screwed up. That’s bad.”

The relationships between other celebrities and organized crime are much tighter.

The famous Japanese singer/songwriter Matsuyama Chiharu personally came to Yuko Inagawa’s funeral and hugged Hideki Inagawa, the son of the gang boss and a gang member at the time, even offering up incense and saying a prayer for the deceased. And in September of 2008, Tadamasa Goto held a lavish birthday bash, in which many of Japan’s famous celebrities attended. The weekly magazine Shukan Shincho wrote it up and named some of the celebrities in attendance but did not name Goto himself. The response was immediate. NHK, the PBS of Japan, banned one famous singer, Akira Kobayashi, from appearing on their channel.

One of the actors in attendance was Rikiya Yasuoka, the one who sang at Tadamasa Goto’s birthday party. The name may not be familiar to American audiences but the face may be. He played a yakuza enforcer who almost kills an American detective (played by Michael Douglas) in Ridley Scott’s suspense-thriller, Black Rain. He does a very good job—method acting at it’s finest.

In the Japanese Blu-Ray release of Black Rain one of the actors who appeared in the film, Guts Ishimatsu, relates an episode where he was asked by the film crew to strip off his shirt and show his tattoos. This perplexed him. “I told the producers, I don’t have any tattoos. I play yakuza, but I’m not a yakuza. Of course, they’d never have a real yakuza in the movie.” Mr. Ishimatsu has also played a role in the film biography of a yakuza boss that was partially filmed in real yakuza offices and released on DVD in July 2008. Takakura Ken, Japan’s greatest actor, starred in many yakuza films and plays the reluctant detective in Black Rain who fights to bring down a particularly vicious yakuza boss with U.S. cops. In 1974, when filming the autobiographical flick, The 3rd Generation Leader of the Yamaguchi-gumi, he met on the set with Taoka-kumicho, the subject of the film, and chummed around with him. There are pictures of them together in the 2009 book, Kobe Geinosha. The links between the crime syndicate and the film-industry elite are almost incestuous.

There are many reasons the connections between Japanese show business and organized crime have not been reported or dealt with, but the chief reasons are two: a complaint and cowardly media, and political protection. For the Osaka Police Department, the close ties between Shimada and the current governor posed a problem. Shimada has purchased real estate at very cheap prices in the Osaka area—the police believe that the yakuza helped him in doing this and an investigation is ongoing. After Shimada announced his retirement, Toru Hashimoto, governor of Osaka since 2008 and a close friend of the star, commented at his August 24 regular press briefing, “If it hadn’t been for Shinsuke-san’s television program there’s no way I would have been elected Governor. I’m where I am now thanks to Shinsuke-san. (The whole thing) is very regrettable and painful.”

A retired Osaka PD officer states, “When the head of the government is close friends with the target of an investigation everyone gets hesitant to pursue a case. It’s only natural. I’m not saying he applied political pressure to squelch our investigation, but there are always bureaucrats at the top who don’t want to piss off the person who ultimately decides our funding.”

On a national level, the Democratic Party of Japan has been supported by the Yamaguchi-gumi since 2007. During the time they have held power, the DPJ appointed Kamei Shizuka as the Minister of Financial Services. In Diet testimony in 1994, Kamei admitted to receiving the equivalent of a $5 million dollar payment from a Yamaguchi-gumi gang boss, Yasuji Ikeda. (Ikeda is missing and presumed dead.) Kamei was also a close associate of Kyo Eichu, an advisor to the Yamaguchi-gumi who is currently serving time for fraud. And recently the former Minister of Foreign Affairs was revealed to have received major political contribution from Jun Shinohara, a convicted criminal (dealing in methamphetamines and tax evasion) who was a consigliore to the Yamaguchi-Goto Gumi. When the government is in bed with the yakuza, it’s hard for the police to execute a crackdown on their business enterprises.

Add to that the fact that police officers sometimes retire to take positions with the talent agencies that have yakuza connections. For these reasons, the TMPD Special Squad has been located in a police department far from the offices of Japan’s major talent agencies.

The Japanese media, while fully aware of the yakuza ties to the entertainment industry, have neglected to report on it for several reasons, primarily because alienating the yakuza-backed talent and promotion agencies means losing access to singers, actors, and celebrities. Major advertising agencies also do big business with Burning Productions and Yoshimoto Kogyo, and alienating these firms could result in losing advertising revenue. Takaharu Ando, the head of the National Police Agency, which has spearheaded the most extensive crackdown on the yakuza in four decades, stated to the press on September 1, “While all of Japanese society moves forward to eliminate the yakuza, it is very saddening that television celebrities, who have tremendous influence on the public, continue to have deep relations with organized crime. In order for Japanese show business to cut their ties with organized crime, the police would like to do everything to help.”

Yet, as the scandal dies down, the press once again grows reluctant to delve any further. No major media outlet has yet dared to discuss Burning Productions.

The decided factor in Yoshimoto Kogyo’s termination of Shimada Shinsuke were a 106 emails sent to the company. The emails date from 2005 to 2007 and were taken from the phone of Yamaguchi-gumi member, ex-boxer and Shimada’s friend Jiro Watanabe. Many have wondered where the mails come from and why they surfaced now. Multiple sources, including those connected to Yoshimoto Kogyo said that they have come to light simply because Tadamasa Goto, who was forced out of the Yamaguchi-gumi on October 14, 2008, is staging a comeback. He wants a cut of Yoshimoto Kogyo, just as in the past he ruled over Japan’s most powerful talent agency, Burning Productions.

A close associate of Goto Tadamasa, Takeshi Sarumaki (not his real name), explains it as follows, “Tadamasa Goto obtained the emails from a former prosecutor and from a cop he has in his pocket, Inspector K. They were part of the evidence in the trial of Watanabe Jiro and Haga Kenji for attempted extortion. He sent out the mails because he’s making a comeback. He’s now tied up with the Kyushu-Seido-kai (PDF) (九州誠道会), Japan’s most violent organized crime group, and some of his old comrades who were expelled with from the Yamaguchi-gumi. Goto has his own associates within Yoshimoto Kogyo. To get a controlling interest, the first thing he has to do is cut off the Kyokushin Rengo ties and at the same time, he gets to take out Shimada whom he strongly dislikes. It’s personal and it’s business.”

Indeed, a former National Police Agency bureaucrat confirmed on background that Goto had been associating with the head of the Kyushu Seido-kai, since at least March of this year, and police have witnessed their meetings. The person who brought the two together is a well-known journalist, who also handles communications between the two when they cannot meet in person.

The National Police Agency considers Tadamasa Goto an active yakuza and the Tokyo Metropolitan Police Department is investigating him on charges of murder and other organized crime related activity.

The problems Japan’s entertainment industry faces in cutting off its ties to the yakuza are tremendous because in many ways Japanese talent agencies and the yakuza are almost one and the same. If they are not successful, they will find that under the new laws that not only will their close ties to the yakuza be exposed, some of their executives will go to jail. It may add serious impetus to cleaning up one of the yakuza’s remaining big businesses. Japanese jails are not nice places to retire.

But one thing should be perfectly clear: While Kitano Takeshi and Takakura Ken have met with yakuza bosses, neither one of them is now an advocate for the yakuza and both have made movies condemning the yakuza, showing them as thugs without honor or humanity who kill ordinary citizens and leech off society. Kitano’s last film, Outrage is the most accurate portrayal of the modern Yakuza ever. The film is a diatribe against them, showing how the traditional yakuza that upheld some primitive code of honor end up being betrayed or killed. The ones that survive are those who are ruthless, backstabbing businessmen—Goldman Sachs with guns.

If you want to understand the modern yakuza, Outrage is a fantastic introductory course. There is a reason that the Japanese public is finally fed up with the yakuza, and it’s because the new breed of yakuza does not live up to any code at all. The Kyushu-Seido-kai has waged violent gang battles with rival groups resulting in the death of civilians and shots fired in hospitals. They lob hand grenades into the houses of their enemies, deal in drugs, and commit armed robbery. In 2006, Goto’s underlings killed a real estate agent who was contesting them over a valuable piece of property—and one of them was convicted of the crime this year. In relation to that killing, in December of 2010, the TMPD put out an international arrest warrant for Kondo Takashi, a former Goto-gumi member and accomplice who was believed to have received direct orders in the killing. In April, Kondo was shot to death in Thailand. TMPD strongly suspect that Goto had him killed. In the traditional yakuza, for an Oyabun (father-figure) to kill his own Kobun (child) would be unthinkable.

Shinsuke Shimada is in a class by himself. The police consider him a yakuza member; he has used their help in procuring lucrative properties and he has invoked the name of the organization to menace people in his way. The press has known this for years. He has worked with the yakuza for his own personal profit. That’s not acceptable.

Shimada Shinsuke not only is suspected of numerous crimes committed with the aid of the yakuza, he has a criminal record for assaulting a 40-year-old woman at his own company and spitting in her face to boot. Goto Tadamasa, the Kyushu-Seido kai, and Shimda Shinsuke are a far cry from the noble yakuza protecting the community, as they are portrayed in the early films of Ken Takakura.

The yakuza are under attack by the police and have had public opinion turned against them because men like Goto Tadamasa, Shimada Shinsuke, and Namikawa, leader of the Kyushu Seido-kai, are no longer oddities in the yakuza world; they are the increasingly becoming the norm. The yakuza are not just Japan’s problem. Entertainment promoters with yakuza connections are operating in the United States. A crime boss recently asked my why I thought that both the U.S. and the Japanese police are trying to crush the yakuza as never before. I had a simple answer. “Goto Tadamasa and Namikawa. Need I say more?” He just sighed and nodded.

Whether they like it or not, the yakuza are going to be removed from Japan’s entertainment industry. They will go with a bang, not a whimper, but they will be eliminated from the industry, just as they were kicked out of the Sumo world. One organized crime detective phrased it eloquently: “The yakuza can walk away or they can be carried out in coffins, but either way, we will see them gone. Ties to the yakuza, just like Shinsuke Shimada, are no longer amusing; after October 1st, they constitute criminal activity.”