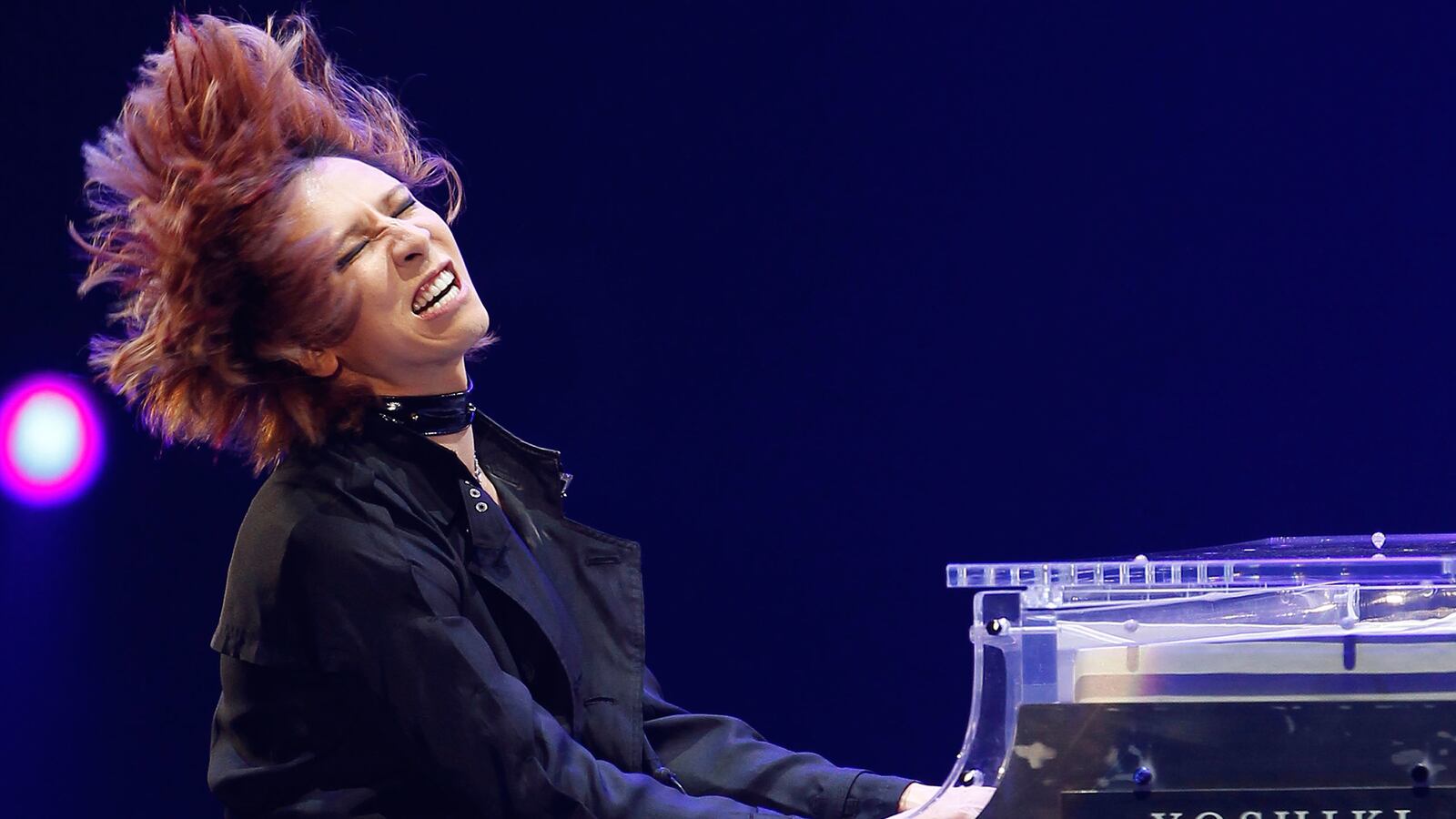

Drama. Brainwashing. Suicide. Speed metal. The story of Japan’s most famous rock gods plays like a soap opera filled with hit records, dark tragedies, bad break-ups, and unexpected reunions, which is why it’s crazy how relatively unknown they are across the Pacific. Now, 34 years after X Japan first formed, enigmatic drummer/composer/front man Yoshiki Hayashi is leading the charge on America as the centerpiece of a rock doc aimed at introducing X Japan to uninitiated Western fans.

Think sex, drugs, and rock ‘n’ roll in the land of the rising sun. Well, minus the drugs. And downplaying the sex. With the ghosts of two deceased band members still looming over the crowds, drawing cheers at every show.

“We don’t do drugs!” exclaims Yoshiki, who’s known by his one-name moniker, chatting with The Daily Beast after the Sundance Film Festival premiere of documentary We Are X. “Never in my entire life!”

“But, lots of drinking,” he admits. His eyes dance behind tinted sunglasses, cascades of sandy hair framing his face in elegant Farrah waves. “We had a normal rock star story, except for the drugs. The sex part? I mean… we have some.”

He laughs, quickly changing the subject.

Over three tumultuous decades, X Japan released five studio albums and six live albums, notching 30 million records sold. Their look and sound charged directly against the mainstream, projecting a nonconformist clash of ideas and opposites, from their flamboyant brand of outré androgyny to the metal-prog sound they pioneered by mashing heavy rock with classical symphonies.

Spearheading the uniquely Japanese visual kei movement with their heavy sound and defiantly gender-bending image, X Japan was deliberately pushing back against the more conservative social order of 1980s Japan.

“It’s all about freedom,” Yoshiki says, reflecting on the band’s androgynous streak. “As long as you don’t do crime, you don’t hurt people, what’s the problem? Why do you have to restrict people’s minds? All X Japan was doing was breaking the wall—wall that separates East and West, or the wall that separates [masculine and feminine], we wanted to break them all. That was our message as well.”

“I’m straight myself,” he continues, “but when I first played the really heavy stuff in the makeup, a critic came to us, saying, ‘What are you guys doing? If you play heavy music, you have to look like a man.’ An army look, something like that. But come on, we were different! I started dressing like a princess and rocking even harder.”

X Japan also racked up many a broken bottle and plenty of fights in their time together, Yoshiki admits, and their shifting lineup reflected deep personal breaks between members of the band.

We Are X explains how X Japan disbanded for 10 years when Yoshiki split from vocalist Toshi Deyama, the childhood friend he co-founded X Japan with. A few years prior, they’d been signed stateside to Atlantic Records—but when Toshi made his public exit in 1997, he went on to decry their rock star lifestyle and the fame and fortune that came with it.

By then, visual kei subculture was declining in popularity anyway. And what drove the core members of X Japan apart was much more cataclysmic. In the film, Yoshiki laments losing his friend to the spiritual cult Home of Heart, which remains unnamed in the doc, after being “brainwashed” by its members. They reunited in 2007 when Toshi disavowed the group and began planning new music for a reunion tour.

Death and mortality penetrate the discography of X Japan, a theme that’s run through Yoshiki’s compositions from the beginning. He counts the death of his father, who killed himself when Yoshiki was young, as the spark of a deep melancholy that he’s been unable to shake his entire life.

“The death of my father changed me completely,” says Yoshiki. “Also, it’s not just death—he killed himself. So my mind was full of questions: Why, why, why, why? But I had to start living with the question: Why do we exist? What’s the reason? I was always thinking of death, always. That very much influenced me. I became a rebel against everything, because everything is questionable. Why do we do this? Why do we do that?”

Director Stephen Kijak (Stones in Exile, Scott Walker: 30 Century Man) also spends time pondering Yoshiki’s relationship with Hide Matsumoto, the beloved guitarist who was found dead in his apartment after hanging himself with a towel. His death, ruled a suicide, sparked several fans to commit copycat suicide. In the film, Yoshiki maintains that he believes Hide died accidentally.

Hide wasn’t the only member of X Japan lost tragically. In 2011, two decades after leaving the band for reasons Yoshiki refuses to explain to this day, troubled bassist Taiji Sawada died after attempting suicide in a Saipan jail cell. I ask Yoshiki to explain what made them part ways all those years ago, but he only musters a halfhearted smile. Instead, he emphasizes that Taiji departed as a member of X Japan, which is how he—and Hide—are still thought of.

“I knew he was not going to live long,” says Yoshiki. “He was kind of homeless. He had a homeless moment. He was labeled handicapped because of alcohol and everything.”

Yoshiki and Toshi invited Taiji back for two massive shows in 2010, which is when, they say, he rejoined X Japan.

“We had two shows in Nissan Stadium with 70,000 people,” recalls Yoshiki. “I brought him. But he was not in a condition to play the entire show, and also we had a bass player. So we played one song together, ‘X’—and that was the last time I saw him. The following year he killed himself.”

“But at that time, he’d rejoined the band,” he smiles. “So now we say there are seven of us.”

Yoshiki, the charismatic figurehead of X Japan, turned 50 last year. His transformation over the decades—starting from the band’s aggressively punk rock early days, when they sported garish kabuki-influenced makeup, spiked blond hair, and gender-bending outfits that shocked the mainstream—can be compared to that of the late David Bowie, another influence.

He met Bowie long ago when they were interviewed together in Japan, an unforgettable moment captured in a photograph that’s seen briefly in the film. “I actually asked him: ‘Where do you draw the line between your true life and your life onstage?’” says Yoshiki. “He couldn’t answer it.”

“He was like, ‘Whoa, that’s a deep question.’ Because some rock stars may just go home and be a normal person. But I was also thinking, where should I draw the line? When I’m eating, should I still eat like a rock star? I thought he was the perfect person to ask.”

X Japan’s initial heavy metal sound got a unique jolt when Yoshiki began introducing elements of his classical training into their music.

“Because we were dressing so crazy, people said we had no talent for music,” he remembers. “I didn’t say at the beginning that I could play classical piano. Actually, at the beginning, I was playing drums but this one club had a piano we couldn’t move from the stage. I thought we might as well use it, and I played Bach.” Yoshiki smiles at the thought. “It freaked people out, and they got even more confused.”

Back when he and Toshi founded the band, heavily influenced by KISS and punk legends like the Sex Pistols, X Japan’s look and sound were aggressively rebellious. Years later, Yoshiki found himself playing a classical concerto by request for the Emperor of Japan, clad in a tuxedo and sporting an elegant blond coif. He’s released a solo classical album, composed for the Golden Globes Awards ceremony, and written for movie soundtracks; worked with David Lynch, who’s briefly seen directing him in an unreleased video in the documentary; and made a cameo in a Tenacious D music video.

Having been close to so much death, Yoshiki still credits art with saving his life. “The music really saved me. Every time I wanted to almost kill myself, or I wanted to break something—well, sometimes I broke it—I started writing lyrics and creating melody,” he says. “If not for music, I don’t think I’d be here. I don’t think I’d have survived. If somebody’s having problems, troubles, something—please watch this. This film can change you.”

Back home and internationally, Yoshiki sits on a huge franchise of his own making. He’s got his own Hello Kitty (Yoshikitty), credit card endorsements, a huge publishing library, even a comic book superhero alter ego created by Marvel icon Stan Lee.

Few people stateside realize he’s been living in Los Angeles for 20 years now—or that one of the biggest rock icons in Japan’s history can be found minutes away from the Sunset Strip, just off the 101, in the private recording studio he bought and tricked out for himself.

Yoshiki purchased his first studio in North Hollywood back in 1993—the very studio in which Metallica recorded their Black Album—after hearing it was especially good for drumming. Alas, it was booked for a year straight. So Yoshiki bought it outright to use for his own personal recording. On occasion, he allowed his pal Michael Jackson to record there.

Given that Yoshiki’s been a relatively low-key Angeleno for years, the film’s climax takes place during a landmark moment for X Japan’s push into American pop culture consciousness: their 2014 concert at Madison Square Garden. In the lead-up to the biggest U.S. show of their career, Yoshiki must confront the physical injuries that years of rocking to the point of collapse have taken on his body. As we chat at Sundance, he’s still sporting the brace on his right forearm where he’s been playing through an injured wrist. But after mulling a crossover attempt for decades, Yoshiki wants to finally make X Japan into an American success, too. He’s been working with the band on new material, including a song he and Toshi are filmed writing during the movie.

“I’m planning on an international tour,” he adds, “but again, it’s like we got a second life. I thought our life was over. So I’m seizing every single moment.”

“When we played a reunion show we played like it was our last show. Every single show is our last show. What I’m trying to say is, we are planning on a big world tour… but, it’s X Japan,” he says. “I don’t know what will happen. Drama still keeps going on.”

What kind of drama this time, I ask?

“Drama,” he smiles bittersweetly. “We’re going to need another documentary.”