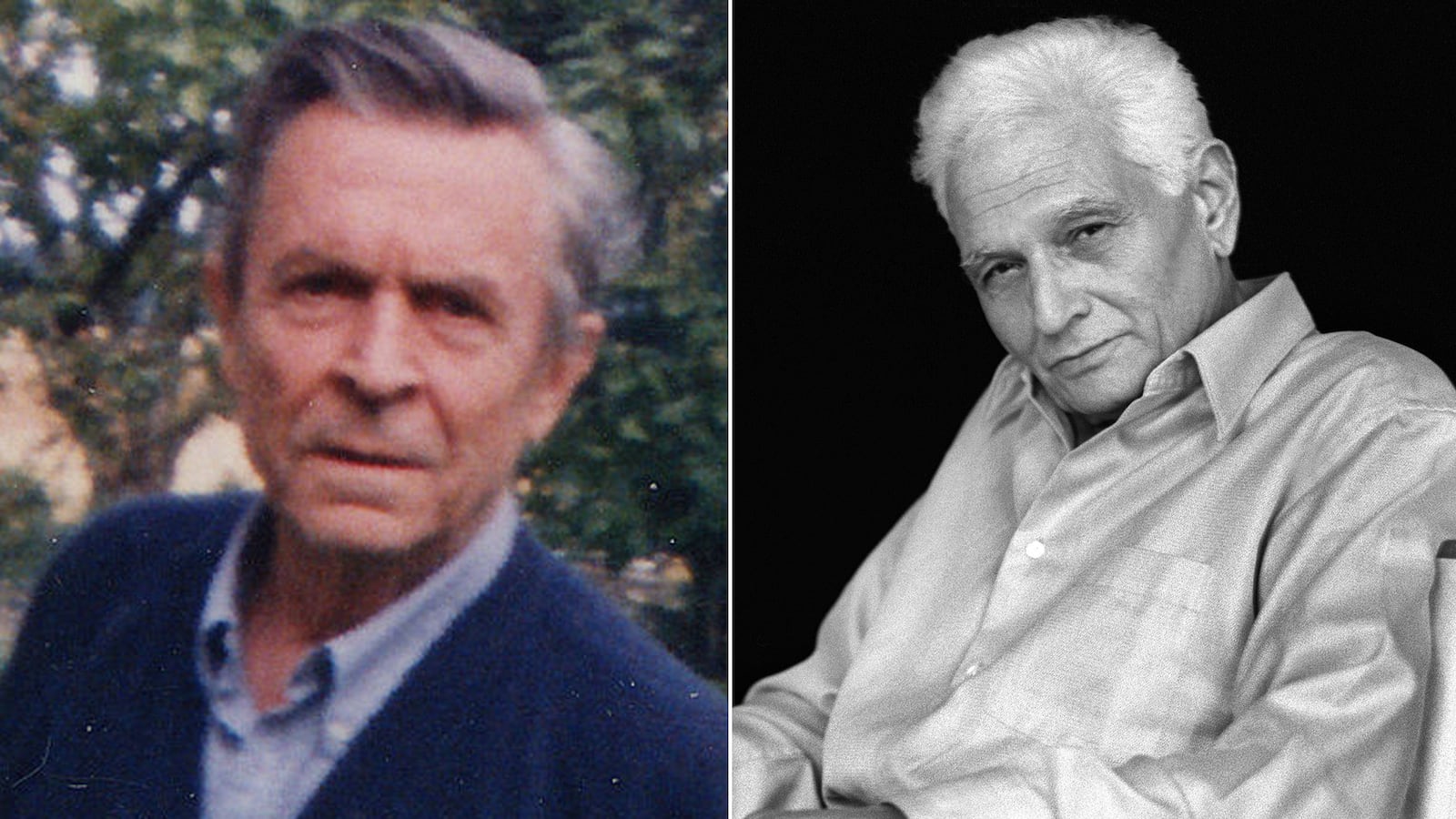

Attacks on Jacques Derrida are nothing new: since the early 1980s, they’ve been a favorite sport of certain other philosophers in his own country, not to mention the American media. Even almost a decade after his death, his ghost manages to find itself at the center of heated combats in the press.In March, an old Derrida nemesis, Jean-Pierre Faye, published a libelle, or a polemical pamphlet, titled Lettre sur Derrida: Combat au-dessus du vide, or Letter on Derrida: Combat Above the Void. It is a title that deliberately evokes Martin Heidegger’s famous “Letter on Humanism,” a text that has long been at the center of heated debates in France. The short book alleges that Derrida used back-door politicking to impose his own vision on the Collège international de philosophie (CIPh), a nontraditional philosophy school formed under President François Mitterrand's administration in 1983. Faye claims that Derrida wanted to force deconstruction on the collège, and in so doing make “the Nazi Heidegger” its “master thinker.”

Faye’s new book arrived just in time for the 30th anniversary of the CIPh, and was framed as a response to biographer Benoît Peeters, whose doorstop of a book on Derrida came out in France in 2007 and depicted Faye as a man who nursed grudges over Derrida’s celebrity, particularly when it came to the CIPh. The collège had initially been Faye’s project, and Derrida was hesitant to get enmeshed, especially after his campaign for a position at a university in Nanterre had ended in humiliation. But the other philosophers and members of the Mitterrand administration who were involved thought it was more natural for someone with Derrida’s international reputation to be the face of the collège, and eventually persuaded him to join. Perhaps unbeknownst to Faye, Derrida had been in contact with French officials for some time about the government’s policy toward philosophy, and had always been seen as an ideal point man for future experiments.

Though the CIPh certainly excited Derrida’s hopes for a university environment that could break free from what he saw as the stifling hierarchy of the French education system, he wasn’t nearly as thrilled with his participation as Faye seems to think. As the collège was taking shape, Derrida wrote to his friend, the Yale literary critic Paul de Man, that he was in “a state of crazy hyperactivity almost completely foreign to my interests and tastes.” In his letters published in Peeters’s biography, Derrida was skeptical that the French government was serious about setting up the institution, and predicted it would come to a “sticky end.” He was wrong about that: he was unanimously elected director of the new college and given fawning media coverage in all of the major French newspapers—another thing that almost certainly aroused Faye’s jealousy. But Derrida never lost his initial pessimism about the CIPh: he departed the position after only three years, later saying that being a director had been “too big a job” and that he “couldn’t handle the cliques.”

Despite the fact that Faye’s new broadside was fueled by well-known personal animus, it has sparked significant media coverage, and an extended debate pitting Faye against both his CIPh co-founders and the school’s current heads. Dominique Lecourt, a philosopher of science who was part of the group that founded the collège, called Faye’s crusade “pathetic.” “Faye always tried to advance his own idea of the institution by judicial artifice,” Lecourt told Le Monde. “According to Derrida, he got harsher and harsher. But in the eyes of the world, it was Derrida who incarnated philosophy, and Faye was unknown.” An editorial in Libération signed by CIPh leaders, including Derrida’s close friend Jean-Luc Nancy, called Faye’s book a brûlot—a rant—that “gives a double history of the Collège and the philosopher that is as malevolent as it is blind.”

The Lettre sur Derrida does not mark the first time Faye has attacked Derrida in public, a feud that seems to be rooted both in institutional battles and Faye’s intensifying philosophical animosity toward Heidegger. Peeters’s book reports that their hostilities began in the 1960s, when Faye fell out with the editors of the influential leftist journal Tel Quel, partly over their translation of Derrida’s philosophy into Marxist terms. Faye tried to recruit Derrida to take his side, but Derrida kept his distance. In 1969, Faye published an infamous attack on the editors of Tel Quel in the newspaper L’Humanité, cryptically linking Derrida’s philosophy to Heidegger’s Nazi politics. Once Faye was openly reducing Heidegger’s philosophy to Nazism and trying to convict Derrida for his “blindness” on the matter, the two became bitter enemies, setting up their later confrontation over the CIPh.

It’s also not the first time Derrida has been a target for his influence by Heidegger. The publication of various books on Heidegger’s Nazi period, especially Victor Farías’s Heidegger and Nazism in 1987, sparked vicious media debates in which Derrida was painted as a defender of a philosophy tainted by National Socialism. Though he had always been critical of Heidegger and insisted he took full account of his master’s dark side, Derrida was often unable to combat the facile media narrative that “deconstruction” masked nihilist politics. That narrative was even more dominant in the American media: his New York Times obituary in 2004 gave extended space to critics who had advanced the notion that Derrida used philosophy to excuse anti-Semitism because of his affinity for Heidegger and his friendship with Paul de Man.

But this time, the polemic has an antiquated feel. The Heidegger debates have cooled in France: though he remains a major point of engagement, and remains influential in the United States, French philosophy has moved past its close identification with his thought. No longer does engagement with Heidegger have major consequences for one’s political reputation. This time, Faye’s attempts to label Derrida as an uncritical disciple of Heidegger, and reject Heidegger’s philosophy as inherently tainted by Nazism, are meeting with annoyance from people who know better.

“According to Faye, one can, in transmitting words, carry entire ideologies with them,” Nancy and company responded in Libération. The philosophers point out that neither Derrida nor Heidegger were the first to use the word “deconstruction,” and Heidegger’s usage in Being and Time was, like most other common terms in Heidegger, carefully qualified as meaning something entirely different than it had in the work of previous thinkers. “A philosophy student knows these are elementary reminders.”

“We must study Heidegger to understand how Europe became what it is,” Nancy added in another interview. “Analyze him while smacking him.” Friends and followers have done the same with Derrida’s work, and it’s no surprise they have little time for critics who want to dismiss him without a debate.