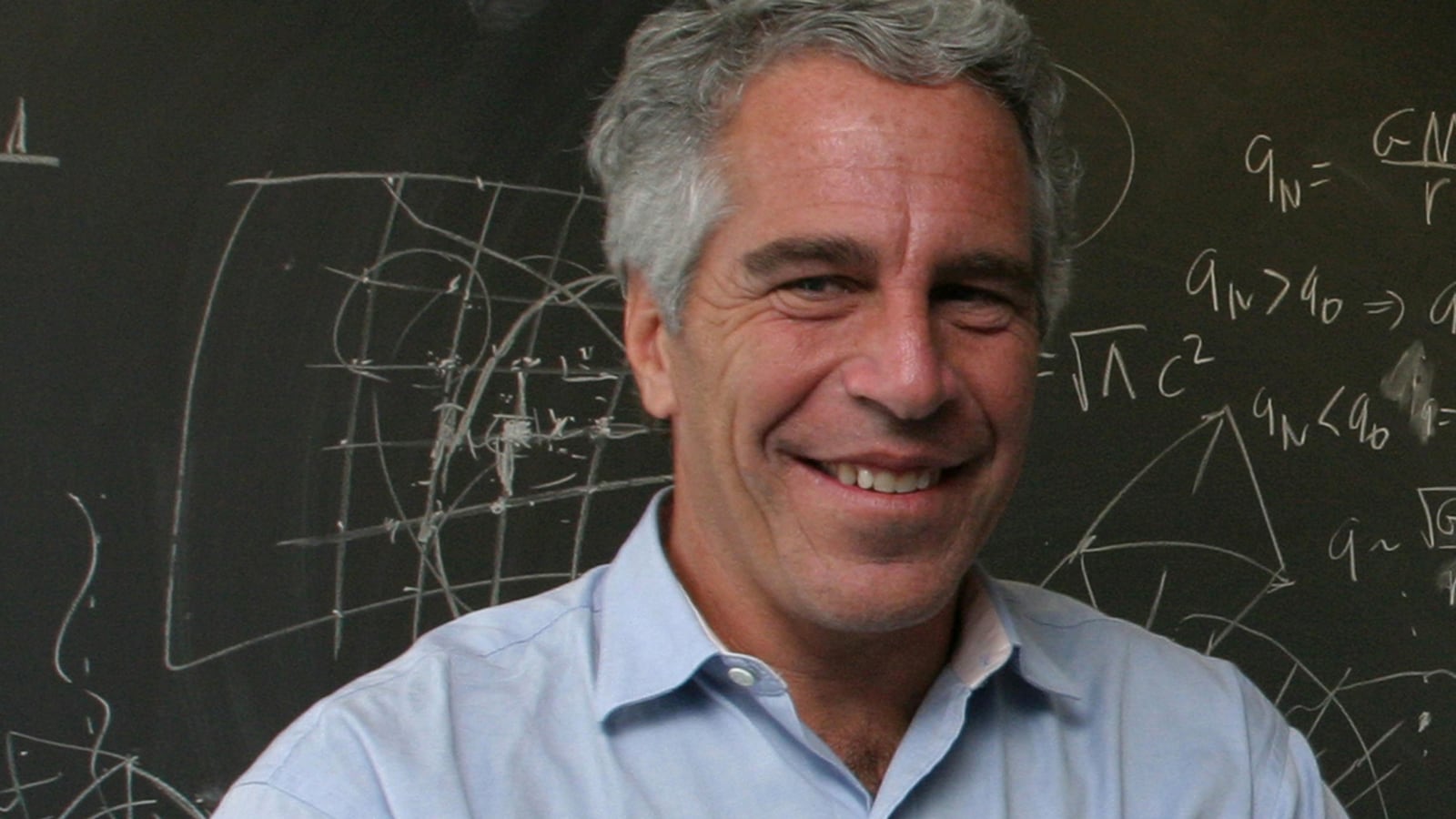

Editor’s note: Jeffrey Epstein was arrested in New York on July 6, 2019, and faced federal charges of sex trafficking and conspiracy to commit sex trafficking. On Aug. 10, 2019, he died in an apparent jailhouse suicide. For more information, see The Daily Beast’s reporting here.

Hedge-fund mogul and sex offender Jeffrey Epstein, who went free this week, lived in a depraved world of thrice-daily massages, pornographic artwork, and hush money—that’s only now being revealed. Conchita Sarnoff follows up on her investigation of the legal wrangling that saved him from a long prison term and reports on the sordid details in part two of her exclusive exposé.

Also:

• Palm Beach’s police chief objected to Epstein’s “special treatment” and gave The Daily Beast an exclusive look at his nine-hour deposition about the investigation.

• Earlier versions of the U.S attorney’s charges, including a sealed 53-page indictment, could have landed Epstein in prison for 20 years.

• Victims alleged that Epstein molested underage girls from South America, Europe, and the former Soviet republics, including three 12-year-old girls brought from France as a birthday gift.

• The victims also alleged trips out of state and abroad on Epstein’s private jets, which would be evidence of sex trafficking—a much more serious federal crime than the state charges Epstein was convicted of.

• Epstein’s attorneys investigated members of the Palm Beach Police Department, while others ordered private investigators to follow and intimidate the victims’ families; one even posed as a police officer.

• Then-Attorney General Alberto Gonzales told The Daily Beast that he “would have instructed the Justice Department to pursue justice without making a political mess.”

Film director Roman Polanski is not the only convicted pedophile to walk free this month and return to a life of privilege. On Wednesday, hedge-fund manager Jeffrey Epstein completes his one-year house arrest in Palm Beach, which has been even less arduous than Polanski’s time at a Swiss ski chalet.

During Epstein’s term of “house arrest,” he made several trips each month to his New York home and his private Caribbean island. In the earlier stage of his sentence for soliciting prostitution with a minor—13 months in the Palm Beach Stockade—he was allowed out to his office each day. Meanwhile, Epstein has settled more than a dozen lawsuits brought by the underage girls who were recruited to perform “massages” at his Palm Beach mansion. Seven victims reached a last-minute deal last week, days before a scheduled trial; each received well over $1 million—an amount that will hardly dent Epstein’s $2 billion net worth.

With that, the known victims of Epstein’s sexual compulsion have been officially silenced, and the case against him is closed, unless new ones come forward. According to banking sources, he has been moving assets out of the U.S. and may well follow Polanski into a luxurious exile.

But the question remains: Did Epstein’s wealth and social connections—former President Bill Clinton; Prince Andrew; former Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak; New Mexico Gov. Bill Richardson; and former Treasury Secretary Larry Summers were just a few of the prominent passengers on his private jets—allow him to receive only a slap on the wrist for crimes that carry a mandatory 20-year sentence? Was he able, with his limitless assets and heavy-hitting lawyers—Alan Dershowitz, Gerald Lefcourt, Roy Black, Kenneth Starr, Guy Lewis, and Martin Weinberger among them—to escape equal justice?

Michael Reiter, the former Palm Beach police chief, certainly thinks so. He gave The Daily Beast exclusive access to the transcript of his nine-hour deposition for the victims’ civil suits, in which he explained how the case against Epstein was minimized by the State Attorney’s Office, then bargained down by the U.S. Department of Justice, all in an atmosphere of hardball legal tactics and social pressures so intense that Reiter became estranged from several colleagues. At the time, Reiter, who retired in 2009 and now runs his own security firm, objected both to Epstein’s plea agreement and to the flexible terms of his incarceration in the county jail rather than state prison. Asked during the deposition whether he thought Epstein received special treatment, he answered “yes.”

In March 2005, Reiter’s department, acting on a complaint from the Florida parents of a 14-year-old girl, launched an investigation that would eventually uncover a pattern of predatory behavior stretching back years and spanning several continents, knowingly enabled by Epstein’s associates and employees. Two or three times a day, whenever Epstein was in Palm Beach, a teenage girl would be brought to the mansion on El Brillo Way. (“The younger the better,” he instructed Haley Robson, a local teenager who was paid to bring other girls to the house, and who declared, on a police tape, that she was “like a Heidi Fleiss,” the infamous California madam.) Advised that she would be giving a “massage,” the girl was then pressured to remove her clothes, submit to fondling and a large vibrator, and sometimes lured into more invasive sexual contact. Each girl was paid $200 or more, depending on how far things went, by house manager Alfredo Rodriguez, who was instructed always to have $2,000 cash on hand.

The Palm Beach Police Department identified 17 local girls who had contact with Epstein before the age of consent; the youngest was 14, and many were younger than 16. And that was just at one of Epstein’s many homes around the world—he also owns property in New York, Santa Fe, Paris, London, and the Caribbean. Subsequent investigation by the FBI, reaching as far back as 2001, identified roughly 40 victims, not counting Nadia Marcinkova, whom Epstein referred to as his “Yugoslavian sex slave” because he had imported her from the Balkans at age 14. Now 24, Marcinkova became a member of the household and is alleged to have participated in the sexual contact with underage girls.

Epstein quickly got wind of the investigation, and progress on the case got messy very quickly. He hired a squad of lawyers and private investigators and dispatched influential friends to pressure the police into backing off. Instead, local detectives pressed on and brought the matter to the attention of the FBI. The detectives asked their federal colleagues whether the fact that some victims appeared to have traveled out of state on Epstein’s planes—plus the use of interstate phone service to arrange assignations—might be violations of the federal 2000 Trafficking Victims Protection Act, which carries a minimum sentence of 20 years. (Florida enacted the federal TVPA in 2002.)

So when State Attorney Barry Krischer, who also ran Florida’s Crimes Against Children Unit, proved reluctant to mount a vigorous prosecution of Epstein, saying the local victims were not credible witnesses, Chief Reiter wrote the attorney a letter complaining of the state’s “highly unusual” conduct and asking him to remove himself from the case. He did not, and the evidence his office presented to a state grand jury produced only a single count of soliciting prostitution. (Krischer has since retired and would not comment for this article.) The day after that indictment was returned, Reiter was relieved to have the FBI step in and take over the investigation.

The details that eventually emerged were often shocking and occasionally bizarre. For Epstein’s birthday one year, according to allegations in a civil suit, he was presented with three 12-year-old girls from France, who were molested then flown back to Europe the next day. These same civil complaints allege that young girls from South America, Europe, and the former Soviet republics, few of whom spoke English, were recruited for Epstein’s sexual pleasure. According to a former bookkeeper, a number of the girls worked for MC2, the modeling agency owned by Jean Luc Brunel, a longtime acquaintance and frequent guest of Epstein’s. Brunel received $1 million from the billionaire around the time he started the agency.

The non-prosecution agreement executed between Epstein and the Department of Justice states that Epstein and four members of his staff were investigated for “knowingly, in affecting interstate and foreign commerce, recruiting enticing and obtaining by any means a person, knowing that person has not yet obtained the age of 18 years and would be caused to engage in commercial sex act”—that is, child sex trafficking. Yet the agreement allowed Epstein to plead guilty to only two lower-level state crimes, soliciting prostitution and soliciting a minor child for prostitution.

Although the police investigation was officially closed, Chief Reiter tried to stay abreast of the federal case against Epstein. He was particularly concerned that Epstein be registered as a sex offender, which was part of the final deal, and that a fund be set up to compensate his victims—which was not, although Epstein agreed to bankroll their civil lawsuits. Dershowitz says Epstein’s agreement to pay attorney fees for the victims and agree to civil damage claims—without admitting guilt—amounted to “extortion under threat of criminal prosecution.”

But exactly which crimes did the Department of Justice threaten to prosecute? The Daily Beast has learned that there were several earlier versions of the U.S. attorney’s charges, including a 53-page indictment that, had he been convicted, could have landed Epstein in prison for 20 years. Brad Edwards, attorney for seven of the victims, confirms the existence of an earlier draft of the non-prosecution agreement, officially under seal, in which it appears that Epstein “committed, at some point, to a 10-year federal sentence.” But in the end Epstein’s legal team refused that deal and threatened to proceed to trial. And that’s where the question of whether the case was “winnable” before a jury again came into play, according to a source in the U.S Attorney’s Office, which shared the state attorney’s view that the prosecution was far from a slam dunk.

For one, it was clear from the start that Epstein would spare no legal expense and that his team of veteran lawyers, whose cases ranged from O.J. Simpson to the investigation of Bill Clinton’s relationship with an intern, would play rough. When the Palm Beach police started to identify victims, according to Det. Joe Recarey’s report, Dershowitz began sending the detective Facebook and MySpace posts to demonstrate that some of these girls were no angels. Reiter’s deposition also states that he heard from local private investigators that Dershowitz had launched background checks on both the police chief and Recarey. Dershowitz denies all of that. According to Reiter, both he and Recarey also became aware that they were under surveillance for several months, without knowing who ordered it. And the Florida victims began to complain that they and family members were being followed and intimidated by private investigators who were then linked to local attorneys in Epstein’s employ. In one reported instance, the private investigator claimed to be a police officer, and Reiter considered filing witness-tampering charges.

The credibility of the victims was also an issue; they had never complained of their treatment by Epstein until they were contacted by police, and they may have voluntarily returned to the Palm Beach mansion several times. Many of the girls came from disadvantaged backgrounds or broken homes, and they were susceptible to Epstein’s cash, intimidation, and charm. Those who were 16 when they went to El Brillo Way would have been in their twenties by the time they took the stand, and Epstein’s investigators had dredged up every instance of bad behavior in their pasts. According to an exchange in the Reiter deposition, a few of the victims had worked in West Palm Beach at massage parlors known as “jack shacks.” Each new compromising detail was immediately forwarded to the State Attorney’s Office, where staff met frequently with Epstein’s lawyers.

The Florida statutes are clear: Any person older than 24 who engages in sexual contact with someone under the age of 18 commits a felony of the second degree. The victim’s prior sexual conduct is not relevant; ignorance of her age is no defense. She needn’t resist physically to cast doubt on the issue of “consent.” For a child under 16, even lewd behavior short of touching is a felony of the second degree. But convincing a jury that a sexual encounter is a heinous crime is difficult if the victim can be made to appear willing and unharmed, not to mention vulgar and mercenary. It wasn’t hard to imagine some of the victims quickly being discredited in court by Epstein’s crack legal team, who repeatedly noted that the age of consent is lower in many other states.

But that doesn’t quite explain why the Department of Justice would forgo the child-trafficking charges, which pertain regardless of a girl’s attitude or character. Epstein’s final sentence is so out of line with the statutory guidelines for that crime that it appears the department may have been influenced by the existence of his many powerful friends and attorneys. A highly intelligent man who once taught math at the Dalton School in New York without a bachelor’s degree, Epstein has been a serious and respected player in the highest reaches of politics and philanthropy. He has made substantial contributions to political candidates, served on the Council on Foreign Relations, and donated $30 million to Harvard University.

Moreover, many of his high-powered acquaintances availed themselves of Epstein’s private jets, for which the pilot logs, obtained by discovery in the civil suits, sometimes showed that bold-face names were on the same flights as underage girls. A high-profile trial threatened to splash mud over all sorts of big players, just as both Gov. Richardson and Hillary Clinton were running for president. Also, a hedge-fund prosecution in which Epstein offered to give evidence was heating up. Alberto Gonzales, who was U.S. attorney general throughout most of the Epstein investigation and resigned just before the non-prosecution agreement was signed, told The Daily Beast that he “would have instructed the Justice Department to pursue justice without making a political mess.” But that may have been an impossible mandate, given the players involved.

Instead, said attorney Brad Edwards, “Epstein committed crimes that should have jailed him for most of his life… he was jailed for only a few months.” And this week he walks through his door a free man.

Conchita Sarnoff has developed multimedia communication programs for Fortune 500 companies and has produced three current events debate television programs, The Americas Forum, From Beirut to Kabul, and a segment for The Oppenheimer Report. She is a contributor to The Huffington Post. She is writing a book about child trafficking in America.