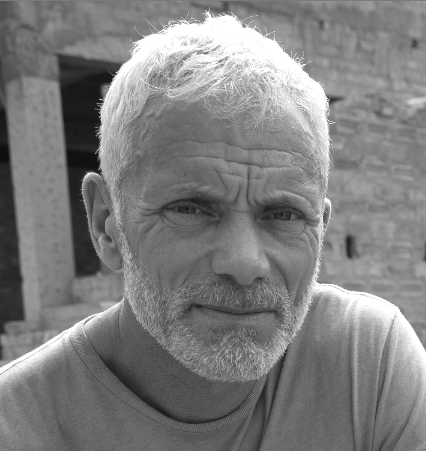

I have a confession to make: For nine years I made a TV show, River Monsters, that left some people believing that everywhere you go, there are fish that can bite pieces out of you or pull you under. But it’s not quite like that.

The fish are real enough—from dog-sized super-piranhas in the Congo to 300-pound river stingrays in South America, and armor-plated alligator gar in the U.S.—and you’d be well advised not to get too close to most of them. But the thing is, they’re really hard to find. So the chances of ever being in the wrong place at the wrong time are reassuringly small.

But (anglers would say) surely that’s the whole thing about big fish: They’re a lot smarter than small fish, and there aren’t so many of them. That’s true, but they haven’t always been as scarce as they are now. Fish have been in our rivers for 300 million years. This decline has happened in just a few human generations—the last 100 years.

Unlike the state of our oceans, which is well documented, this story isn’t widely known. It’s something that has slowly revealed itself to me over 35 years, during my travels to far-flung rivers. Partly it’s from historical records, but mostly it’s oral history, which nobody has ever collated or written down. It’s a vast database, but it exists only in the memory of the old fishermen, who are dying as we speak.

So why am I telling you this now? Because it has a significance that goes way beyond making my life harder when I’m on a film shoot.

Long before I worked in TV I was a biology teacher, and in science-speak most of the fish that I go after are apex predators—they sit at the top of the food pyramid. That makes them really good indicators of the health of the whole river. If the apex predator is there, you can normally assume that the rest of the pyramid is there too—the middle-sized fish that they eat, the small fish that they eat, and all the bugs and plankton that they eat. But if the apex predator is not there, it suggests that something is wrong.

Take a minute for a quick thought experiment. Imagine someone discovering that they have an abnormally low count of white blood cells (the apex predators of the bloodstream). What do they do? They go for more tests, as a matter of urgency. They want to find out how serious this is, and what’s the prognosis. Most importantly, they want to know what can be done about it. What they don’t do is ignore it.

Now consider what is often said about our rivers: that they are our planet’s arteries. If that’s the case, then what I’ve been doing since 1982, without realizing it until very recently, is taking blood samples. And the results demand investigation.

The obvious—and simple—explanation for the decline of these top predators is overfishing. But it could be a symptom of something more serious. That’s the real worry. And it’s important we look into this because we are water-based life forms too. Water doesn’t just cycle from rivers to oceans to clouds to rain and back to rivers again—it flows through every one of us, through every cell in our bodies. So we all have a vested interest in the state of our planet’s water.

This was the genesis of Mighty Rivers, and it was an insight that meant putting everything else on hold. But where to begin? How can you make any meaningful survey of the world’s rivers in a half-dozen programs? It was a challenge that seemed impossible—like trying to film goonch catfish underwater in the Himalayas, or catch a 250-pound arapaima from the Amazon on a fly rod, or swim with oarfish at night in a mile and a half of water. But we’d been there and done all that, in River Monsters season 1, 6 and 8 respectively.

More of a challenge, perhaps, was making a show about “the environment” that people would want to watch. But here again we had our River Monsters heritage to draw on. Strange as it may seem now, we faced a similar challenge nine years ago. A conventional program about “fishing” is never going to attract a big audience, or a diverse audience. But River Monsters did both, to spectacular effect, by busting out of existing categories and creating its own genre.

Will Mighty Rivers achieve the same? My fervent hope is that it will achieve more, in its own special way. That’s not just a fisherman’s blind optimism speaking. A fisherman’s faith is always rooted in realism. And make no mistake: I’m still fishing. But this time I’m not just fishing for fish—I’m fishing for answers, I’m fishing for surprises, and I’m fishing for hope. And I’m fishing for an audience that I know is out there, who are interested in looking at fish and rivers and water and the world in a new way.

I’ll see you on the riverbank.