A month ago, I drove a half-cooked leg of lamb around the foot of the Santa Rita Mountains to Jim Harrison’s place on Sonoita Creek in southeastern Arizona. The lamb was half-cooked because I’d planned to finish it off in Jim’s oven while our dogs played. Jim lived on one of southern Arizona’s last permanent streams, a ribbon of rich habitat known for its giant cottonwoods, native fishes, and vast array of birds and butterflies. It’s a place buzzing with life. We drank wine out back while the dogs splashed in the creek, backlit in the winter sunlight. I hold on to that image now: Jim, America’s greatest living writer, died there last Saturday afternoon.

The Harrison place is a functional, one-story ranch house perched just above the high-water level of the creek. It’s a little more than a casita. Just west of the small town of Patagonia, the house is isolated, though there’s a county road that crosses the creek about a hundred yards upstream. It has a low stone wall and even abandoned tennis courts. Some of my own history unfolded here. My two children fondly remember many barbeques, often featuring the dove and quail we hunted nearby. Jim and I would grill doves next to the stand of Carrizo that blocked off his house from the sight of hordes of frenzied birdwatchers who, during the ’90s, gathered on the road to watch the rare Mexican blue mockingbird that had chosen to live at Harrison’s house. Occasionally, Jim had to fire his .22 magnum, the snake gun that he used to train his bird dogs, in the air to thin out the crowds. When the Harrisons traveled, they trusted me to move in for a week or so and take care of their beloved English setters, Tess and Rose. I was allowed into the wine cellar but rationed to one bottle of Domaine Tempier Bandol per day. I hunted each morning with the dogs, and they revealed to me a hidden doggy universe.

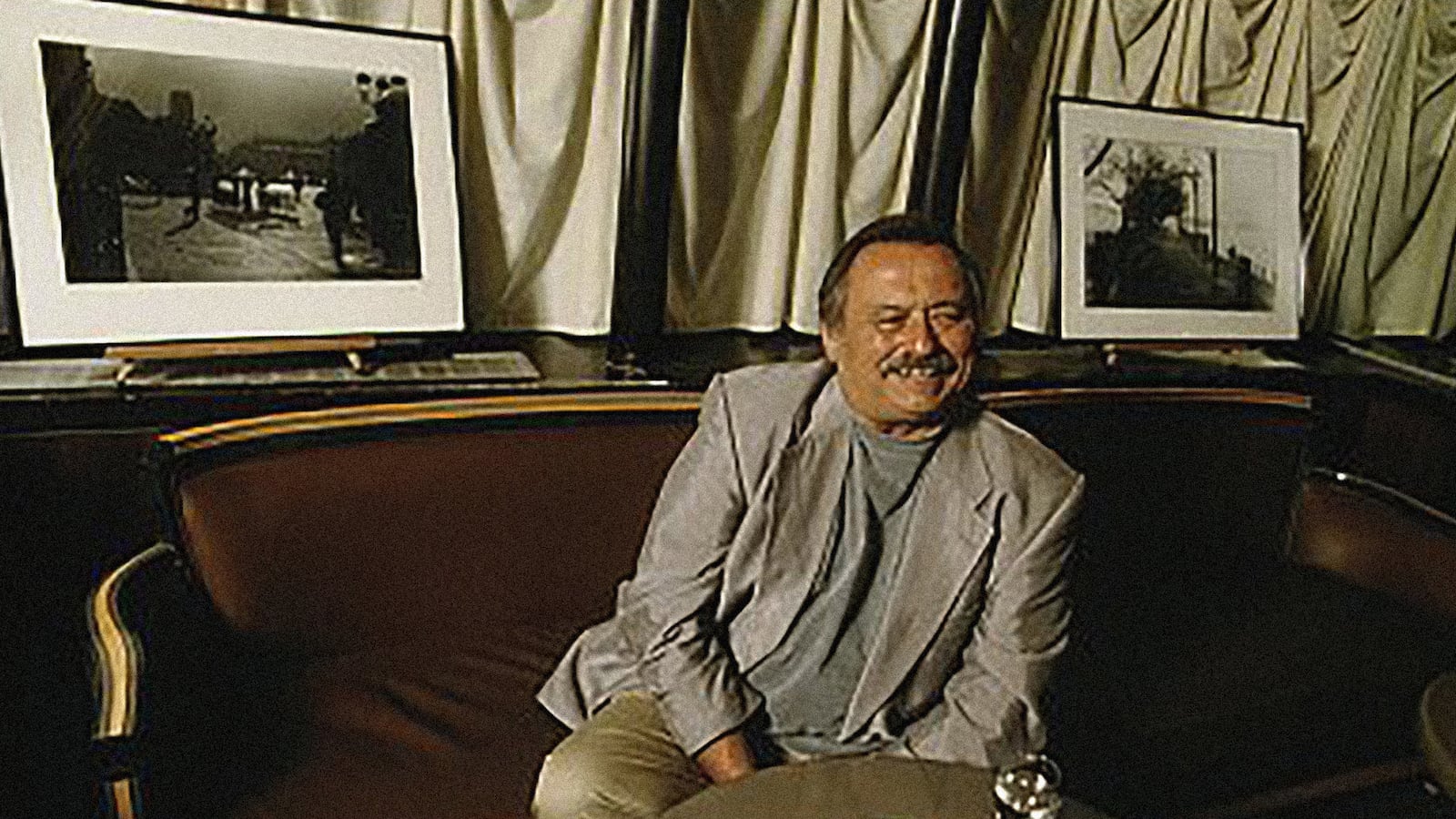

I met Jim Harrison in northern Michigan in 1981, the same year my daughter was born. I called him from my parents’ place up on Thumb Lake and he said come on over. Russell Chatham and Guy de la Valdene were there, and all three guys cooked separate, elaborate entrees. Fresh from hanging out with grizzly bears in the Northern Rockies, I wasn’t used to such laborious and spirited cuisine. By the time I staggered out the door, Harrison had tucked a bottle of 1971 Lafite under my arm—not a bad way to treat a stranger.

Between then and the time he bought his little house on Sonoita Creek, Harrison and I took a number of camping trips, mostly in the Southwest as he had little interest in meeting a grizzly bear. This was in the ’80s. We visited the Cabeza Prieta and camped in the Baboquivaris. I took him down to the Seri coast of Sonora, Mexico. On a wild mesa overlooking the Sea of Cortez, I actually got a huge backpack on Jim, the only time in my knowledge he ever put one on. I had to hook the waist strap under his considerable belly. The pack was so heavy with Mexican beer and a bottle of tequila that we had to abort our hike. In the boot hill of New Mexico, up in the empty Animus Mountains, we perhaps set a world record for cold-cooking putenesco over an oak fire. I wore fingerless gloves chopping the garlic while the olive oil congealed on the outside of the skillet. We sat around the blazing fire digesting Italian sausage and watching tiny elf owls flit in the firelight from one live oak to the next.

A few years later, Jim called from Michigan and asked me to meet him in Salt Lake City. He was field-testing a new SUV for Car and Driver. The magazine wanted a Harrison road story (I never knew Jim to look under the hood of any vehicle). We drove into the slickrock of southeast Utah and climbed down into a canyon where we visited a panel of ancient petroglyphs carved into the rock. In the dark patina, a pair of cranes danced between a set of life-sized wolf tracks. Here was a shamans’ lair. Jim, with his bottomless curiosity, just sat there, taking it in. Later, we camped out on a precipitous finger of rock that jutted out into Canyonlands National Park. It was one of Edward Abbey’s two favorite camping sites, and it fell off vertically for hundreds of feet in three directions. Jim’s acrophobia kicked in when I lay my sleeping bag down next to the rim. The next morning, we returned to the valley floor, a necessary compromise.

Jim Harrison was one of the most generous men I ever knew. He lent countless thousands to dozens of less fortunate friends who needed help; he seldom if ever got paid back and that didn’t stop him. Jim would invent jobs for me when he thought I was broke. He lent money to my ex-wife that I never knew about. When traveling he kept his single good eye out for a paucity of tip, the dangerous baldness of tires, or the looming mortgage payment. He took care of working writers like Chuck Bowden and Jack Turner. That generosity extended to sharing his time with younger and beginning writers who he encouraged and sometimes mentored throughout his life. At my wife Andrea’s bookstore, Jim was always up for signing books by the box-load. One night in 2011, when Jim was sicker than shit and Linda was in the hospital with a coma, he crawled up on the stage at a benefit and read with Peter Matthiessen—Livingston, Montana’s greatest literary night.

Of course, I knew his books. My friend William Eastlake gave me a galley proof of Jim’s first novel Wolf, which Bill had blurbed. Years later, Jim berated me for leaving that galley in geodesic dome of a hippie college friend who lived deep in the woods of Ontario: “Do you know how much that thing is worth?”

After I read his first two novels, nothing he wrote surprised me except perhaps the speed and ease with which he churned out Legends of the Fall. It was just a matter of time. When he began working on Dalva, Jim hired me to do “research.” I wrote up my field notes from the months that I spent exploring the wild region of Baja’s southern gulf coast, which Jim embedded verbatim in the novel. Dalva remains my favorite book.

Three decades later, our houses are by chance ten miles apart in the same Montana valley. Sometimes I’d take my dog River over there to play with Harrison’s dog Folly. The last time I went to his house was last fall when his wife of 55 years, Linda King Harrison, died.

In early February of this year, Andrea and I picked up some white menudo at the Little Mexico Restaurant in Tucson and made the drive to Patagonia, careful to pull into Jim’s driveway at 3:30 p.m. sharp—a punctuality we always observed but never talked about. He was working as hard as I’d ever seen him, taking naps between bouts of writing, “It’s the only thing I know how to do,” he kept saying. Jim was shirtless, still suffering from the lingering neuralgia of shingles and his pants were falling off the crack of his ass. “I want my wife back but can’t have her,” he’d say. Jim still had his dog; a housekeeper would come over and feed him and he still went to the Wagon Wheel bar in the afternoon for drinks. But it was lonely out there.

The day they found Jim dead, our friend Phil Caputo was called over to say goodbye before the medics moved him: Jim was “on the floor of his study, where he’d fallen from his chair, apparently from a heart attack.” Phil wrote. “He’d died a poet’s death, literally with a pen in his hand, while writing a new poem.”

I smile as I remember the lighthearted macho shit I gave Harrison after he and Caputo got lost bird hunting east of the head of Sonoita Creek and spent a freezing night huddling around a cottonwood fire until the Arizona Fish and Game wardens came and found them the next morning.

Back home, I look out my window at the fresh snow blanketing the valley between the Absoroka Mountains and the foothills of the Gallatin Range, north toward Jim’s place. There’s a hole in the sky.