Today, there are over 200 LGBT student centers in the United States.

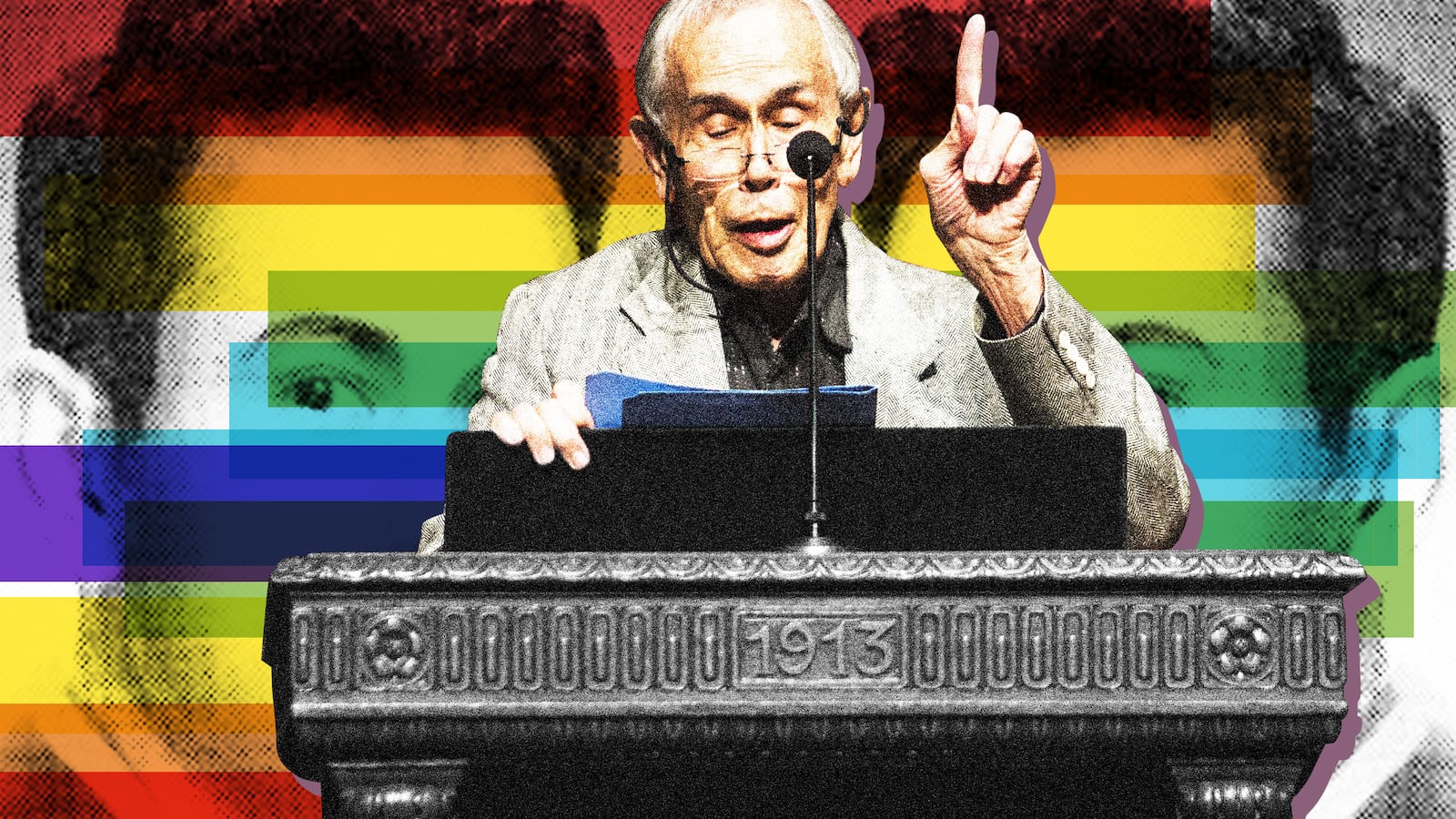

But in 1971, when gay activist Jim Toy founded the Human Sexuality Office at the University of Michigan with lesbian activist Cyndi Gair, there were zero.

“I think it was one desk and two chairs and a filing cabinet,” the 88-year-old Toy told The Daily Beast, laughing at the barrenness of the single room the university provided.

The HSO wouldn’t even be able to include terms like “lesbian” or “gay” in its official title until the 1980s for fear, as Toy recalls, of offending donors or losing funding for the public university.

After all, 1971 was only two years after the Stonewall riots. It was also two years before the American Psychiatric Association would remove homosexuality from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.

So it was a miracle, all things considered, that the HSO came into being when it did—one of only two such offices to be founded in the 1970s, according to an online list maintained by the Consortium of Higher Education LGBT Resource Professionals. It would take until 1991 for there to be 10 LGBT student centers in the United States.

As the website for the Spectrum Center—as the HSO is now called—notes, the office was founded under “increased pressure” from the campus chapter of the Gay Liberation Front, an advocacy group that was active in the wake of the Stonewall riots. Even then, the university only gave the HSO enough funding at first for two quarter-time positions.

There was no model for the HSO to follow because such an office had never existed before. Asked whether he was excited or nervous to be venturing into uncharted territory, Toy told The Daily Beast, “I think it was both.”

“Oh, what are getting into here?” Toy remembers thinking.

“But it was exciting absolutely,” he added.

In addition to supporting LGBT students, the HSO advocated for change within the university itself. The institutional fights the HSO took on, however, proceeded at an almost glacial speed: It took 15 years before the name could be changed to the University of Michigan Lesbian Gay Male Programs Office because the university originally wanted to, as Toy playfully puts it, be “circumspect in its use of language.”

And it took 21 years, as the Spectrum Center website notes, for Toy and his fellow advocates to successfully get sexual orientation added as a protected category in the University of Michigan’s non-discrimination policy—one of Toy’s signature accomplishments during his time at the school.

Back in 1971, Toy had no idea that the work of the HSO would take so long.

“When we got going, naïve me [thought], ‘Oh, we’re going to change the political climate in the United States!’” Toy told The Daily Beast, before adding that Anita Bryant’s anti-gay activism “five or six years down the road” robbed him of that notion.

The University of Michigan also faced criticism from anti-LGBT critics in the 1970s over the founding of the HSO.

A master’s thesis by Eric William Denby catalogues the “full-throated opposition to the hiring of two known homosexuals” that was sparked by the initial media coverage of the office. As Denby noted, conservative writer Russell Kirk penned a column bemoaning the fact that the University of Michigan now had “services for sodomites and lesbians in the student body,” referring to Toy and Nair as “sexual deviates.”

It is perhaps no surprise that progress was hard-won while the University of Michigan was under such intense scrutiny. Even something as simple as changing the name of the HSO involved persistent behind-the-scenes campaigning before it paid off.

“It was a challenge,” Toy remembers. “We kept advocating for the change, and dealt with the frustration, and [then] there we were.”

By 1995, as the Spectrum Center website notes, the words “bisexual” and “transgender” had been added to the title, before the name was shortened to its current form.

Toy has been pleased by the explosion of LGBT student centers that has taken place since 1971. By 1994, when Toy stepped down as director, there were three dozen LGBT student centers in the United States, according to the Consortium of Higher Education LGBT Resource Professionals website. Three years later, there were about 50.

“I’m so glad that all these institutions of higher learning have come along as they have over time,” Toy said, adding that he “would be glad” if LGBT young people today knew more about what “we had to deal with” back then.

Some of those problems from 1971 have been troublingly persistent: The rate of suicide among LGBT youth is still alarmingly high. For Toy, it is the thought of lives saved that matters most to him now as he looks back on his time at the University of Michigan. “Former students have come back to campus and contacted me and said, ‘If it had not been for you in the office, I would have killed myself.’”

The LGBT student centers of today continue the same vital work as that original HSO but often in a more fully-fleshed out form.

In order to be counted as an LGBT campus center by the Consortium of Higher Education LGBT Resource Professionals, an office must have at least one half-time staffer whose “primary responsibility” is “providing LGBT services,” as the Consortium website notes—and many today more than clear that bar, offering a wide range of programming to students while campaigning for change at the institutional level.

“They have become multi-faceted—I’ll use that jargon—entities,” Toy said.

Toy continued to work for the University of Michigan after stepping down as director. He officially retired in 2008, although he prefers to use the term “advancement” to “retirement.”

Asked how he was spending his “advancement,” Toy immediately pointed out to The Daily Beast that the state of Michigan doesn’t have protections for LGBT people in its nondiscrimination law, nor in its hate crime legislation.

“That’s a campaign that I continue to be involved with,” he said.

But surely Toy can look back with pride at his 1971 accomplishment, The Daily Beast suggested—especially considering that the first LGBT student center has since been multiplied two-hundredfold.

“The word ‘proud’ is not in my vocabulary about that time,” Toy replied. “The word ‘grateful’ is.”