In the days after President Kennedy’s assassination, the legendary columnist Jimmy Breslin set the standard for literary journalism written in the wake of tragedy. His columns for the New York Herald Tribune became instant classics, precisely because he chose to cover the unexpected human stories at the heart, but on the periphery, of the breaking news.

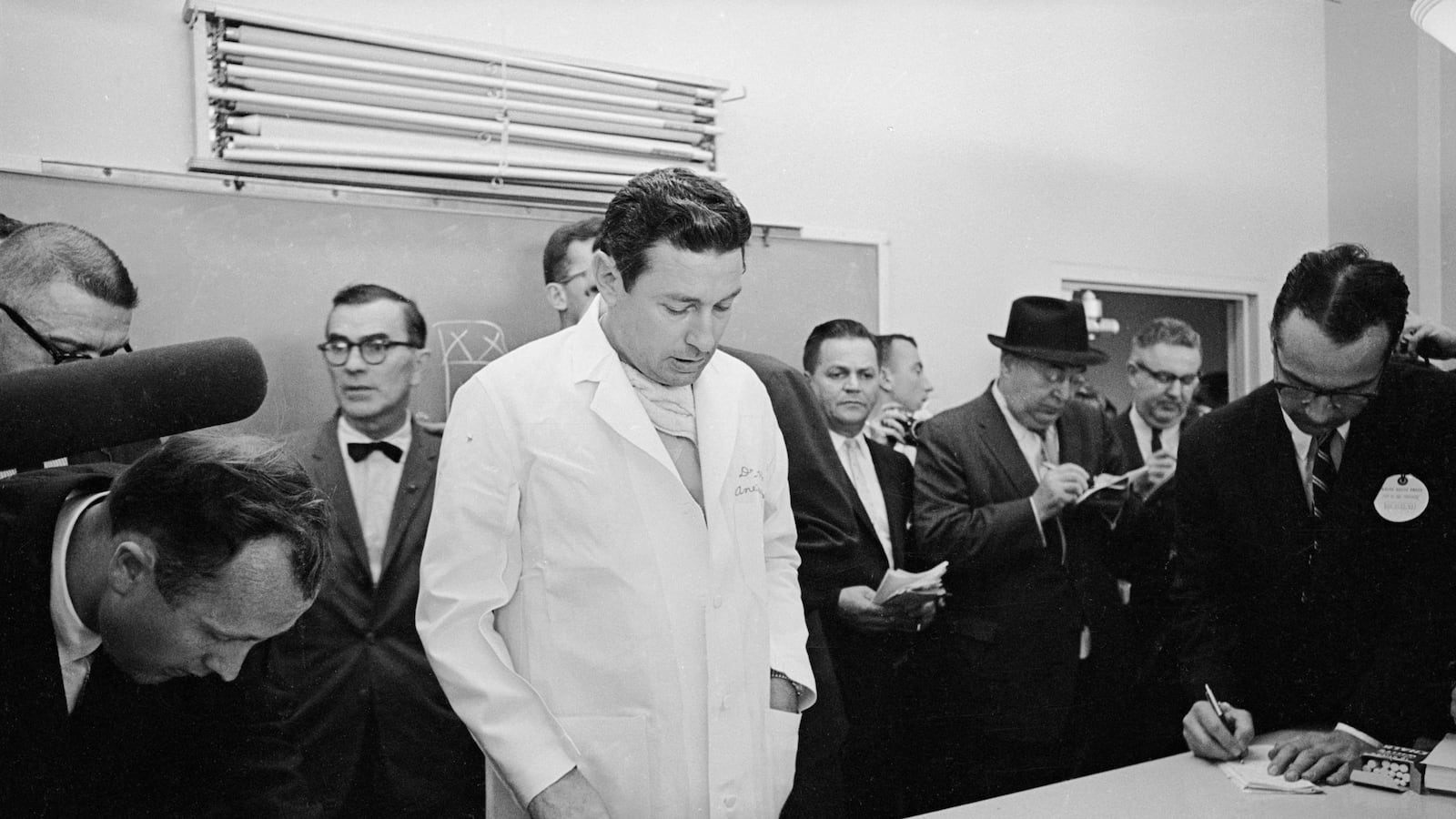

Published below with Breslin’s permission, his iconic column from those tumultuous days. “A Death in Emergency Room One” chronicles Nov. 22, 1963, from the attending emergency-room surgeon in Dallas.

You can also read his other, “It’s an Honor” which has become a staple of journalism schools because Breslin sidestepped the media circus and covered the president’s burial from the perspective of the gravedigger at Arlington National Cemetery.

These columns are true short stories, history written in the present tense.

‘A Death in Emergency Room One’

New York Herald Tribune, Nov. 24, 1963

By Jimmy Breslin

DALLAS—The call bothered Malcolm Perry. “Dr. Tom Shires, STAT,” the girl’s voice said over the page in the doctor’s cafeteria at Parkland Memorial Hospital. The “STAT” meant emergency. Nobody ever called Tom Shires, the hospital’s chief resident in surgery, for an emergency. And Shires, Perry’s superior, was out of town for the day. Malcolm Perry looked at the salmon croquettes on the plate in front of him. Then he put down his fork and went over to a telephone.

“This is Dr. Perry taking Dr. Shires’ page,” he said.

“President Kennedy has been shot. STAT,” the operator said. “They are bringing him into the emergency room now.”

Perry hung up and walked quickly out of the cafeteria and down a flight of stairs and pushed through a brown door and a nurse pointed to Emergency Room One, and Dr. Perry walked into it. The room is narrow and has gray tiled walls and a cream-colored ceiling. In the middle of it, on an aluminum hospital cart, the president of the United States had been placed on his back and he was dying while a huge lamp glared in his face.

John Kennedy had already been stripped of his jacket, shirt, and T-shirt, and a staff doctor was starting to place a tube called an endotracht down the throat. Oxygen would be forced down the endotracht. Breathing was the first thing to attack. The president was not breathing.

Malcolm Perry unbuttoned his dark blue glen-plaid jacket and threw it onto the floor. He held out his hands while the nurse helped him put on gloves.

The president, Perry thought. He’s bigger than I thought he was.

He noticed the tall, dark-haired girl in the plum dress that had her husband’s blood all over the front of the skirt. She was standing out of the way, over against the gray tile wall. Her face was tearless and it was set, and it was to stay that way because Jacqueline Kennedy, with a terrible discipline, was not going to take her eyes from her husband’s face.

Then Malcolm Perry stepped up to the aluminum hospital cart and took charge of the hopeless job of trying to keep the 35th president of the United States from death. And now, the enormousness came over him.

Here is the most important man in the world, Perry thought.

The chest was not moving. And there was no apparent heartbeat inside. The wound in the throat was small and neat. Blood was running out of it. It was running out too fast. The occipitoparietal, which is a part of the back of the head, had a huge flap. The damage a .25-caliber bullet does as it comes out of a person’s body is unbelievable. Bleeding from the head wound covered the floor.

There was a mediastinal wound in connection with the bullet hole in the throat. This means air and blood were being packed together in the chest. Perry called for a scalpel. He was going to start a tracheotomy, which is opening the throat and inserting a tube into the windpipe. The incision had to be made below the bullet wound.

“Get me Doctors Clark, McCelland, and Baxter right away,” Malcolm Perry said.

Then he started the tracheotomy. There was no anesthesia. John Kennedy could feel nothing now. The wound in the back of the head told Dr. Perry that the president never knew a thing about it when he was shot, either.

While Perry worked on the throat, he said quietly, “Will somebody put a right chest tube in, please.”

The tube was to be inserted so it could suction out the blood and air packed in the chest and prevent the lung from collapsing.

These things he was doing took only small minutes, and other doctors and nurses were in the room and talking and moving, but Perry does not remember them. He saw only the throat and chest, shining under the huge lamp, and when he would look up or move his eyes between motions, he would see this plum dress and the terribly disciplined face standing over against the gray tile wall.

Just as he finished the tracheotomy, Malcolm Perry looked up and Dr. Kemp Clark, chief neurosurgeon in residency at Parkland, came in through the door. Clark was looking at the president of the United States. Then he looked at Malcolm Perry and the look told Malcolm Perry something he already knew. There was no way to save the patient.

“Would you like to leave, ma’am?” Kemp Clark said to Jacqueline Kennedy. “We can make you more comfortable outside.”

Just the lips moved. “No,” Jacqueline Kennedy said.

Now, Malcolm Perry’s long fingers ran over the chest under him and he tried to get a heartbeat, and even the suggestion of breathing, and there was nothing. There was only the still body, pale white in the light, and it kept bleeding, and now Malcolm Perry started to call for things and move his hands quickly because it was all running out.

He began to massage the chest. He had to do something to stimulate the heart. There was not time to open the chest and take the heart in his hands, so he had to massage on the surface. The aluminum cart was high. It was too high. Perry was up on his toes so he could have leverage.

“Will somebody please get me a stool,” he said.

One was placed under him. He sat on it, and for 10 minutes he massaged the chest. Over in the corner of the room, Dr. Kemp Clark kept watching the electrocardiogram for some sign that the massaging was creating action in the president’s heart. There was none. Dr. Clark turned his head from the electrocardiogram.

“It’s too late, Mac,” he said to Malcolm Perry.

The long fingers stopped massaging and they were lifted from the white chest. Perry got off the stool and stepped back.

Dr. M.T. Jenkins, who had been working the oxygen flow, reached down from the head of the aluminum cart. He took the edges of a white sheet in his hands. He pulled the sheet up over the face of John Fitzgerald Kennedy. The IBM clock on the wall said it was 1 p.m. The date was November 22, 1963.

Three policemen were moving down the hall outside Emergency Room One now, and they were calling to everybody to get out of the way. But this was not needed, because everybody stepped out of the way automatically when they saw the priest who was behind the police. His name was the Reverend Oscar Huber, a small 70-year-old man who was walking quickly.

Malcolm Perry turned to leave the room as Father Huber came in. Perry remembers seeing the priest go by him. And he remembers his eyes seeing that plum dress and that terribly disciplined face for the last time as he walked out of Emergency Room One and slumped into a chair in the hall.

Everything that was inside that room now belonged to Jacqueline Kennedy and Father Oscar Huber and the things in which they believe.

“I’m sorry. You have my deepest sympathies,” Father Huber said.

“Thank you,” Jacqueline Kennedy said.

Father Huber pulled the white sheet down so he could anoint the forehead of John Fitzgerald Kennedy. Jacqueline Kennedy was standing beside the priest, her head bowed, her hands clasped across the front of her plum dress that was stained with blood which came from her husband’s head. Now this old priest held up his right hand and he began the chant that Roman Catholic priests have said over their dead for centuries.

“Si vivis, ego te absolvo a peccatis tuis. In nomine Patris et Filio et Spiritus Sancti, amen.”

The prayer said, “If you are living, I absolve you from your sins. In the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Ghost, amen.”

The priest reached into his pocket and took out a small vial of holy oil. He put the oil on his right thumb and made a cross on President Kennedy’s forehead. Then he blessed the body again and started to pray quietly.

“Eternal rest grant unto him, O Lord,” Father Huber said.

“And let perpetual light shine upon him,” Jacqueline Kennedy answered. She did not cry.

Father Huber prayed like this for 15 minutes. And for 15 minutes Jacqueline Kennedy kept praying aloud with him. Her voice did not waver. She did not cry. From the moment a bullet hit her husband in the head and he went down onto his face in the back of the car on the street in Dallas, there was something about this woman that everybody who saw her keeps talking about. She was in shock. But somewhere, down under that shock some place, she seemed to know that there is a way to act when the president of the United States has been assassinated. She was going to act that way, and the fact that the president was her husband only made it more important that she stand and look at him and not cry.

When he was finished praying, Father Huber turned and took her hand. “I am shocked,” he said.

“Thank you for taking care of the president,” Jacqueline Kennedy said.

“I am convinced that his soul had not left his body,” Father Huber said. “This was a valid last sacrament.”

“Thank you,” she said.

Then he left. He had been eating lunch at his rectory at Holy Trinity Church when he heard the news. He had an assistant drive to the hospital immediately. After that, everything happened quickly and he did not feel anything until later. He sat behind his desk in the rectory, and the magnitude of what had happened came over him.

“I’ve been a priest for 32 years,” Father Huber said. “The first time I was present at a death? A long time ago. Back in my home in Perryville, Missouri, I attended a lady who was dying of pneumonia. She was in her own bed. But I remember that. But this. This is different. Oh, it isn’t the blood. You see, I’ve anointed so many. Accident victims. I anointed once a boy who was only in pieces. No, it wasn’t the blood. It was the enormity of it. I’m just starting to realize it now.”

Then Father Huber showed you to the door. He was going to say prayers.

It came the same way to Malcolm Perry. When the day was through, he drove to his home in the Walnut Hills section. When he walked into the house, his daughter, Jolene, 6 and a half, ran up to him. She had papers from school in her hand.

“Look what I did today in school, Daddy,” she said.

She made her father sit down in a chair and look at her schoolwork. The papers were covered with block letters and numbers. Perry looked at them. He thought they were good. He said so, and his daughter chattered happily. Malcolm, his 3-year-old son, ran into the room after him, and Perry started to reach for him.

Then it hit him. He dropped the papers with the block numbers and letters and he did not notice his son.

“I’m tired,” he said to his wife, Jennine. “I’ve never been tired like this in my life.”

Tired is the only way one felt in Dallas yesterday. Tired and confused and wondering why it was that everything looked so different. This was a bright Texas day with a snap to the air, and there were cars on the streets and people on the sidewalks. But everything seemed unreal.

At 10 a.m. we dodged cars and went out and stood in the middle lane of Elm Street, just before the second street light; right where the road goes down and, 20 yards further, starts to turn to go under the overpass. It was right at this spot, right where this long crack ran through the gray Texas asphalt, that the bullets reached President Kennedy’s car.

Right up the little hill, and towering over you, was the building. Once it was dull red brick. But that was a long time ago when it housed the J.W. Deere Plow Company. It has been sandblasted since and now the bricks are a light rust color. The windows on the first three floors are covered by closed venetian blinds, but the windows on the other floors are bare. Bare and dust-streaked and high. Factory-window high. The ugly kind of factory window. Particularly at the corner window on the sixth floor, the one where this Oswald and his scrambled egg of a mind stood with the rifle so he could kill the president.

You stood and memorized the spot. It is just another roadway in a city, but now it joins Ford’s Theatre in the history of this nation.

“R.L. Thornton Freeway. Keep Right,” the sign said. “Stemmons Freeway. Keep Right,” another sign said. You went back between the cars and stood on a grassy hill which overlooks the road. A red convertible turned onto Elm Street and went down the hill. It went past the spot with the crack in the asphalt and then, with every foot it went, you could see that it was getting out of range of the sixth-floor window of this rust-brick building behind you. A couple of yards. That’s all John Kennedy needed on this road Friday.

But he did not get them. So when a little bit after 1 o’clock Friday afternoon the phone rang in the Oneal Funeral Home, 3206 Oak Lawn, Vernon B. Oneal answered.

The voice on the other end spoke quickly. “This is the Secret Service calling from Parkland Hospital,” it said. “Please select the best casket in your house and put it in a general coach and arrange for a police escort and bring it here to the hospital as quickly as you humanly can. It is for the president of the United States. Thank you.”

The voice went off the phone. Oneal called for Ray Gleason, his bookkeeper, and a workman to help him take a solid bronze casket out of the place and load it onto a hearse. It was for John Fitzgerald Kennedy.

Yesterday, Oneal left his shop early. He said he was too tired to work.

Malcolm Perry was at the hospital. He had on a blue suit and a dark blue striped tie and he sat in a big conference room and looked out the window. He is a tall, reddish-haired 34-year-old, who understands that everything he saw or heard on Friday is a part of history, and he is trying to get down, for the record, everything he knows about the death of the 35th president of the United States.

“I never saw a president before,” he said.

‘It’s An Honor’

New York Herald Tribune, November 1963

By Jimmy Breslin

WASHINGTON -- Clifton Pollard was pretty sure he was going to be working on Sunday, so when he woke up at 9 a.m., in his three-room apartment on Corcoran Street, he put on khaki overalls before going into the kitchen for breakfast. His wife, Hettie, made bacon and eggs for him. Pollard was in the middle of eating them when he received the phone call he had been expecting. It was from Mazo Kawalchik, who is the foreman of the gravediggers at Arlington National Cemetery, which is where Pollard works for a living. “Polly, could you please be here by 11 o’clock this morning?” Kawalchik asked. “I guess you know what it’s for.” Pollard did. He hung up the phone, finished breakfast, and left his apartment so he could spend Sunday digging a grave for John Fitzgerald Kennedy.

When Pollard got to the row of yellow wooden garages where the cemetery equipment is stored, Kawalchik and John Metzler, the cemetery superintendent, were waiting for him. “Sorry to pull you out like this on a Sunday,” Metzler said. “Oh, don’t say that,” Pollard said. “Why, it’s an honor for me to be here.” Pollard got behind the wheel of a machine called a reverse hoe. Gravedigging is not done with men and shovels at Arlington. The reverse hoe is a green machine with a yellow bucket that scoops the earth toward the operator, not away from it as a crane does. At the bottom of the hill in front of the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, Pollard started the digging (Editor Note: At the bottom of the hill in front of the Custis-Lee Mansion).

Leaves covered the grass. When the yellow teeth of the reverse hoe first bit into the ground, the leaves made a threshing sound which could be heard above the motor of the machine. When the bucket came up with its first scoop of dirt, Metzler, the cemetery superintendent, walked over and looked at it. “That’s nice soil,” Metzler said. “I’d like to save a little of it,” Pollard said. “The machine made some tracks in the grass over here and I’d like to sort of fill them in and get some good grass growing there, I’d like to have everything, you know, nice.”

James Winners, another gravedigger, nodded. He said he would fill a couple of carts with this extra-good soil and take it back to the garage and grow good turf on it. “He was a good man,” Pollard said. “Yes, he was,” Metzler said. “Now they’re going to come and put him right here in this grave I’m making up,” Pollard said. “You know, it’s an honor just for me to do this.”

Pollard is 42. He is a slim man with a mustache who was born in Pittsburgh and served as a private in the 352nd Engineers battalion in Burma in World War II. He is an equipment operator, grade 10, which means he gets $3.01 an hour. One of the last to serve John Fitzgerald Kennedy, who was the 35th president of this country, was a working man who earns $3.01 an hour and said it was an honor to dig the grave.

Yesterday morning, at 11:15, Jacqueline Kennedy started toward the grave. She came out from under the north portico of the White House and slowly followed the body of her husband, which was in a flag-covered coffin that was strapped with two black leather belts to a black caisson that had polished brass axles. She walked straight and her head was high. She walked down the bluestone and blacktop driveway and through shadows thrown by the branches of seven leafless oak trees. She walked slowly past the sailors who held up flags of the states of this country. She walked past silent people who strained to see her and then, seeing her, dropped their heads and put their hands over their eyes. She walked out the northwest gate and into the middle of Pennsylvania Avenue. She walked with tight steps and her head was high and she followed the body of her murdered husband through the streets of Washington.

Everybody watched her while she walked. She is the mother of two fatherless children and she was walking into the history of this country because she was showing everybody who felt old and helpless and without hope that she had this terrible strength that everybody needed so badly. Even though they had killed her husband and his blood ran onto her lap while he died, she could walk through the streets and to his grave and help us all while she walked.

There was Mass, and then the procession to Arlington. When she came up to the grave at the cemetery, the casket already was in place. It was set between brass railings and it was ready to be lowered into the ground. This must be the worst time of all, when a woman sees the coffin with her husband inside and it is in place to be buried under the earth. Now she knows that it is forever. Now there is nothing. There is no casket to kiss or hold with your hands. Nothing material to cling to. But she walked up to the burial area and stood in front of a row of six green-covered chairs and she started to sit down, but then she got up quickly and stood straight because she was not going to sit down until the man directing the funeral told her what seat he wanted her to take.

The ceremonies began, with jet planes roaring overhead and leaves falling from the sky. On this hill behind the coffin, people prayed aloud. They were cameramen and writers and soldiers and Secret Service men and they were saying prayers out loud and choking. In front of the grave, Lyndon Johnson kept his head turned to his right. He is president and he had to remain composed. It was better that he did not look at the casket and grave of John Fitzgerald Kennedy too often. Then it was over and black limousines rushed under the cemetery trees and out onto the boulevard toward the White House. “What time is it?” a man standing on the hill was asked. He looked at his watch. “Twenty minutes past three,” he said.

Clifton Pollard wasn’t at the funeral. He was over behind the hill, digging graves for $3.01 an hour in another section of the cemetery. He didn’t know who the graves were for. He was just digging them and then covering them with boards. “They’ll be used,” he said. “We just don’t know when. I tried to go over to see the grave,” he said. “But it was so crowded a soldier told me I couldn’t get through. So I just stayed here and worked, sir. But I’ll get over there later a little bit. Just sort of look around and see how it is, you know. Like I told you, it’s an honor.”