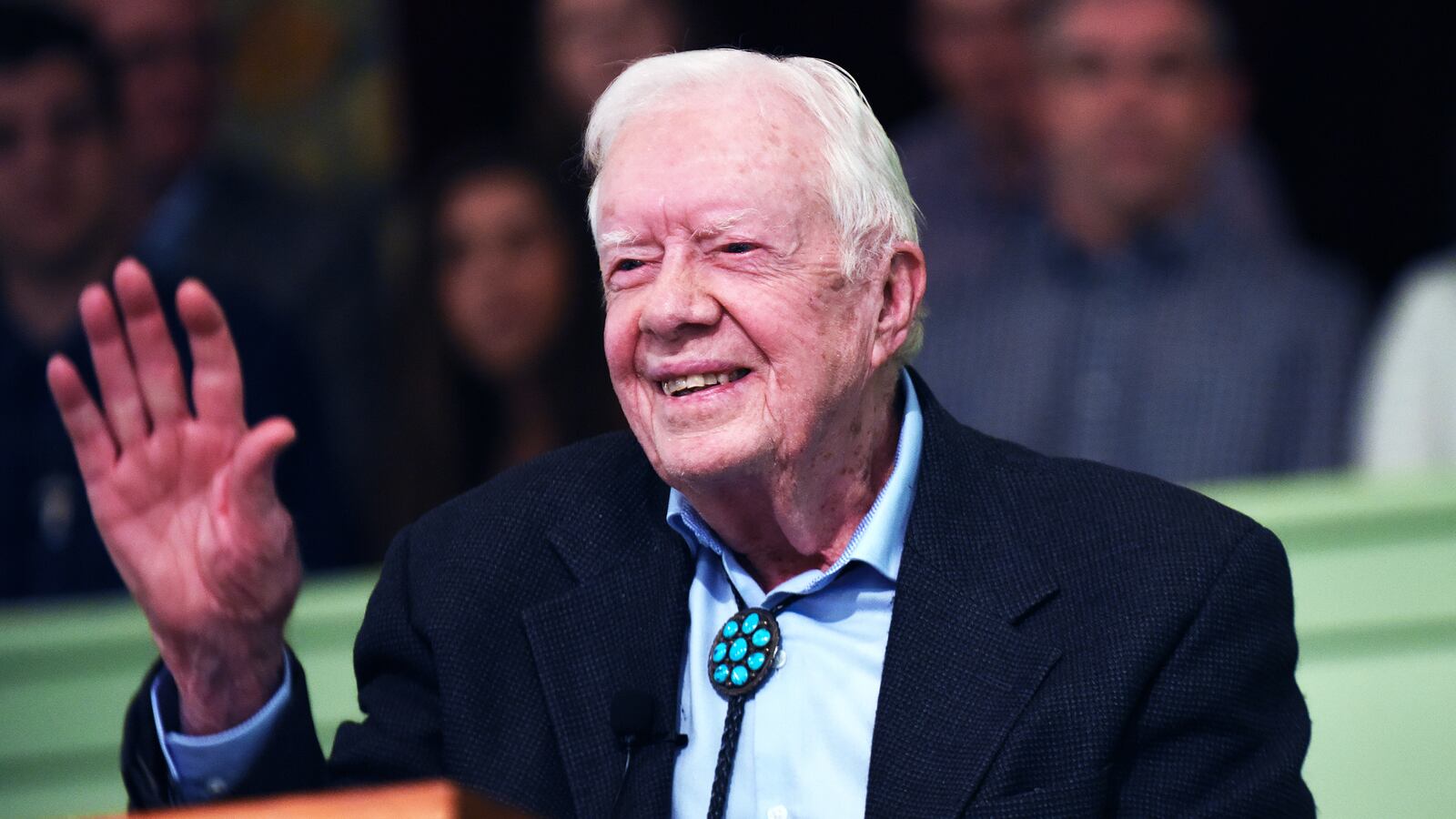

Jimmy Carter has had complex relationships with all of his successors. This excerpt from His Very Best: Jimmy Carter, a Life, by Jonathan Alter, explores Carter’s contacts with President George H.W. Bush and President Barack Obama, all three of whom Alter interviewed for his biography.

It was no secret that Carter was not a member in good standing of the ex-presidents’ club, in part because he never accepted their code. The unwritten rules aren’t complicated: Until the Trump era, former presidents were expected to build their libraries and at least try to hold their tongues about the incumbent, not complain—as Carter often did—that the policy is wrong or they are underused by the president. No one sitting in the Oval Office likes the idea of a freelance secretary of state. The challenge for them was managing their high-maintenance predecessor.

After George H. W. Bush was elected in 1988, Secretary of State James Baker consulted Carter often. Carter helped Bush out in Panama in 1989 by confronting Manuel Noriega after he rigged an election. He told the dictator and his henchmen, “You are thieves.” But his most conspicuous early diplomatic success was in Nicaragua, which he visited eight times in a five-year period.

In February 1990, for the first time since the Russian Revolution, a Communist regime (the Sandinistas) lost a democratic election. If the shocking results held, Violeta Chamorro, a newspaper publisher, would replace President Daniel Ortega and become the first female head of state in the Americas.

But five decades had passed since the last peaceful transfer of power in Nicaragua, and this one was by no means assured. Ortega had been confident of reelection—all the polls showed him well ahead—and he was not inclined to relinquish power. The Carter Center monitored the election, and, after finding it fair, Carter met with Ortega late into the night. He told Ortega, who had followed the familiar trajectory of dashing revolutionary to repressive thug, that he knew what it felt like to lose and that he could perhaps make a comeback someday. (He did.) Carter’s personal experience in 1980 impressed Ortega, and he left office peacefully.

President Bush was thrilled with Carter’s role. “This sent a powerful message throughout the region and to Moscow,” he recalled. Later, Carter resolved devilishly complex disputes between the Sandinistas and those whose property they had seized during their revolution.

In the run-up to the 1991 Gulf War, Carter’s relationship with Bush turned sour. Carter felt passionately that Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait wasn’t worth going to war over, even though Bush cited the 1980 Carter Doctrine (which decreed that the U.S. had vital interests in the Persian Gulf) in justifying it. The former president said so publicly, then took matters a fateful step further, writing each member of the UN Security Council and urging them to vote against the United States on the resolution authorizing coalition forces to intervene. Canadian prime minister Brian Mulroney received Carter’s letter and alerted the Bush White House. Carter argued that there was no difference between expressing one’s views publicly and privately. Bush, who recalled “working night and day” to bring the allies aboard, vehemently disagreed. “We only have one president at a time,” he said in 2016. He was appalled that a former president would “foment opposition to the policy objective of his own country.” Even many Democrats felt Bush had the better argument.

Carter didn’t care about procedural niceties or whether Bush would stop liking him. When he was trying to keep the bullets from flying, his Plains friend Jill Stuckey explained, he never “gave a rat’s ass what people thought of him.” Former Carter speechwriter Rick Hertzberg noted that Americans admire ruthlessness in the waging of war but not peace. Carter was “a Patton of peace,” Hertzberg said, referring to General George S. Patton, whose single-minded devotion to achieving his objectives during World War II was remembered longer than the harsh criticism he received from many contemporaries for improper behavior. Bush’s apoplectic team briefly considered charging Carter with violation of the Logan Act, the 1799 federal law that criminalizes unauthorized negotiation with a foreign power.

Bush himself was more merciful. After he won UN approval and liberated Kuwait, he dropped the matter. In 2006 Carter infuriated Bush again when he used his eulogy at Coretta Scott King’s funeral to implicitly criticize President George W. Bush’s response to Hurricane Katrina the year before. Bush Sr. thought Carter’s comments about his son were “out of line and untrue,” but at the end of his life, he made a point of saying, “I respect this good man.”

Just after the 2008 election, outgoing president George W. Bush invited all of the living former presidents to the White House for a private lunch with President-Elect Obama. A memorable Oval Office photograph shows the Bushes, Bill Clinton, and Obama chatting like old friends on the left, with Carter standing alone on the right. One of the presidents confided later that the photo perfectly captured the chemistry of their meeting and lunch that day. The other presidents gave Obama convivial advice on the peculiarities of the office, while Carter wanted to press his serious policy agenda. Carter later told Brian Williams of NBC News that the body language was deliberate because “I feel that my role as a former president is probably superior to that of other presidents.” Judging by the amount of golf the others played over the years while Carter was doing good in Africa, this was an accurate but—as he recognized—ill-advised statement. The next day he tried to walk back the boast by saying he meant to refer to the “good deeds” of the Carter Center.

In October 2017 the five living former presidents, including new member Obama, gathered at Texas A&M University to raise money for hurricane relief. In the holding area, aides saw on their phones a column by Maureen Dowd in The New York Times entitled “Jimmy Carter Lusts for a Trump Posting.” In it, Carter admitted that at Zbigniew Brzezinski’s funeral, he had lobbied President Trump’s (second of several) national security adviser, H. R. McMaster, to be dispatched to North Korea, and—not coincidentally—he refused to say anything negative about Trump. At the same time, he didn’t hold back on his Democratic successors. Carter said that Obama “reneged” on his early promise to work on Mideast peace and that he went overboard on authorizing drone strikes, especially in Yemen, a country that the always-adventurous Carter, late in life, called the most fascinating he had ever visited. (He even tried khat, a shrub used in the Horn of Africa as a stimulant.)

During Obama’s first term, neither the president nor Secretary of State Hillary Clinton had any interest in Carter’s advice. He described his relationship with them as “nonexistent,” which, in the case of Obama, whom he had admired greatly in 2008, was personally hurtful. The fact that he and Obama had only ceremonial contacts embittered Carter and—in his mind—freed him to knock the president, as he had Clinton. Carter had known embattled Syrian president Bashar al-Assad since he was an ophthalmology student, and he publicly criticized Obama for issuing futile demands for Assad’s removal. Obama’s second-term secretary of state, John Kerry, was more solicitous of Carter and checked in regularly to see what he had learned about Syria peace plans in his meetings with Vladimir Putin and other leaders. Kerry found that even at ninety, Carter still had fresh information and penetrating insights into geopolitics.

As he reflected on his own presidency, Obama came to feel that Carter had been misunderstood and deserved better from history. “He was mocked for the solar panels [that Carter placed on the roof of the White House in 1979] but he was prescient and he brought environmental concerns out of the counterculture and directly into U.S. policymaking,” Obama said in 2020. “He introduced an explicit language around human rights and what previously had been an afterthought in foreign policy.” Obama saw Carter as an important prod for his successors, who learned from him that “it wasn’t enough to talk about America as being a beacon for freedom as JFK or Ronald Reagan did, but that it had to mean something.” And he found Carter’s post-presidency inspiring: “His voice has meant a better life for many people around the world.”

From HIS VERY BEST: Jimmy Carter, a Life by Jonathan Alter. Copyright © 2020 by Jonathan Alter. Reprinted by permission of Simon & Schuster, Inc.