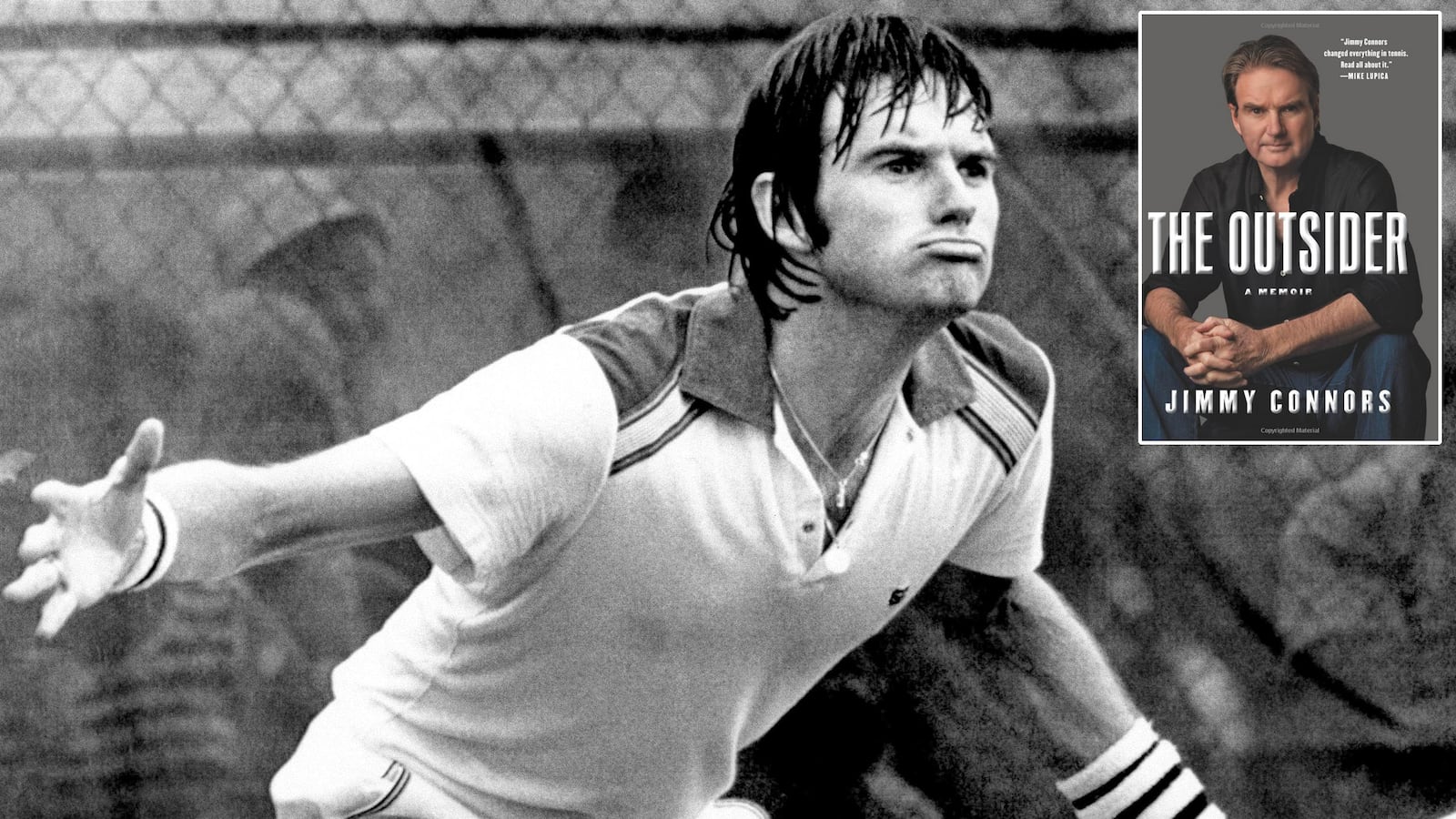

He was crass. He grunted and groaned. He had floppy, sweaty hair like an Argentine soccer star. He yelled at the umpires and swore at his opponents, sometimes crossing to the other side to get in their face. He played to the crowd—recall the shameless fist-pumping, knee-lifting huckstering during the 1991 match with Aaron Krickstein. He had that short-guy attitude: insecure and just daring you to challenge him about it. To anyone born in the 1960s or earlier, he was what he gave: a middle finger straight in the face of America.

I couldn’t help be simultaneously repelled and mesmerized by The Outsider, Jimmy Connors’s already maligned autobiography.

It is certainly disappointing. Andre Agassi’s Open raised the stakes in 2009: the insipid, poorly written, bland sports celebrity memoir was no longer a given. It could be better. It could have heart and revelation and introspection and delicious storytelling—of course for Agassi much of that can be laid at the laptop of J.R. Moehringer, who ghostwrote Open.

But Connors slinks back to the same tromping ground that aroused David Foster Wallace’s disappointment in the brilliant “How Tracy Austin Broke My Heart,” his 1994 review of Beyond Center Court. There are the humble roots in gritty East St. Louis and 90-minute commutes each way to the nearest practice court. There are the doting mother, wild brother, and distant father. And there are plenty of the precooked auto-responses to major milestones. Connors’s first U.S. Open appearance in 1970: “it just felt like the next step in a natural progression.” His breakthrough tournament was when he beat Stan Smith, Dick Stockton, and Arthur Ashe in the 1973 U.S. Pro in Boston: “That first big win not only felt overdue but good—really good.”

Connors captured eight Grand Slam titles. He still holds the men’s records for reaching the most Grand Slam quarters (41), for staying in the top 10 the longest (817 weeks), and for winning the most pro tournaments (109). He popularized the two-handed backhand and perhaps more than anyone else moved tennis from the country club to join golf as the unofficial fifth and sixth major sports in the country.

On the tour Connors was widely known as a jerk. A lot of people picking up the memoir will want to learn otherwise, that he was misunderstood, that the stories were false. John McEnroe, his bête noire, wrote in his 2002 memoir, You Cannot Be Serious, about his first meeting with Connors. It was in the locker room before their semifinal match at the 1977 Wimbledon—Mac, the boy wonder who had qualified; Jimmy, the top dog. McEnroe went up to say hello to Connors, and Connors just walked past him. Did this happen? Yes, Connors writes in his usual sarcastic, elbow-to-the-ribs-of-the-guy-on-the-barstool-next-to-you way: “I’m nothing if not gracious.” He was trying to rattle McEnroe. (It worked.)

Agassi recalled another locker-room scene, in the 2006 U.S. Open, his final tournament. When he came in after losing in the third round, the players, trainers, officials, and even the security guard all stood, clapped, and whistled for the retiring hero. Everyone but Connors. “He’s leaning against a far wall with a blank look on his face and his arms tightly folded,” Agassi writes.

Connors says it was true. His reasoning is odd: “Not me, not my style. I wasn’t trying to deliberately disrespect him; I just didn’t care about him, and he didn’t affect my life in any way.” Really? Then why spend a couple of pages trashing Agassi, hammering him for knocking tennis in Open, for sinking low in the rankings midcareer and, in a long, parenthetical paragraph, for rejecting an apparent offer of coaching from Connors?

A big kerfuffle during the launch of the book has been about Connors claiming, without actually stating, that Chris Evert had an abortion just before they were supposed to get married in 1974. How did this affect him? He only says that he partied hard after getting the news and then lost in his next tournament. He blamed the abortion and the late night for this blemish on his otherwise almost perfect 1974 season. It is hard not to think Connors is an insensitive cad for bringing up such a private matter almost 40 years after the fact. Connors ends the chapter on Evert by saying they were unable to answer the question, “Can two number ones exist in the same family?” Indeed, countless couples, famous or not, have faced that.

Nonetheless, amid the tournament-to-tournament recitations over his incredibly long career, Connors ends up revealing quite a lot about himself. He has obsessive-compulsive disorder and ocular motor sensory deficit (he has trouble reading). He cheated while a freshman at UCLA: “I was busted. It was the best one year of college I ever attended.” He cheated on his wife. He almost succeeded Pat Sajak as the host of Wheel of Fortune. He loves backgammon and Pepsi and gambling: he bet on himself each June at Wimbledon and once lost $70,000 on a single hand at blackjack—he hit on 16 and got 20, and the dealer hit on 16 and got 21. He was close friends with Ilie Nastase and loved to party with him at the Playboy Club in London, where he first met his wife, Patti, a Playmate (Miss November 1976). He stashed notes from his grandmother in his socks and would look at them during changeovers.

Besides going after “a dishonest prick” who wrote that Connors was doing cocaine during changeovers at the 1980 Wimbledon, Connors doesn’t try to settle too many scores in The Outsider à la Agassi. He even apologizes to Johnny Carson (during a Las Vegas match attended by Carson, Connors yelled “Fuck you! Fuck you! Fuck you!” flipping the bird at the crowd) and expresses regret about the way he treated his coach Pancho Segura, whom he pushed out of his entourage. Although engulfed by endless lawsuits against his brother John (over investments in a riverboat-casino company) and his former business partner Bill Riordan (over prize money from matches), he doesn’t rip them. Most of all, he grapples fairly honestly with the legacy of his mother, Gloria, the hard-charging woman who dominated his life as coach and manager (they talked 10 times a day) until her death six years ago.

The book has some juice. The passage about the 1991 U.S. Open when Connors got past Krickstein and made it all the way to the semis at age 39 is vintage Connors: “‘Isn’t this what they paid for? Isn’t this what they want?’ Now we’re in a fifth-set tiebreaker and I’m talking directly into a courtside camera. I mean what I am saying. I have total respect for the people in the seats around me and I am not going to disappoint them.” But there is no transformation to give the book real tension. As he writes, “Mellowed? Screw that.” The main humanizing detail for Connors, now 60, might be in the three pages he devotes to his dogs, the half-dozen retrievers, terriers, and huskies that have been his retirement “in-house shrinks.” “No matter how impatient or cranky I got, they forgave me. Even writing this now, I have tears in my eyes. I’d give anything to have my dogs back with me.”

He is the same now as he ever was: he describes angrily selling his stake in the Champions Tour and getting arrested for a confrontation at a 2008 college basketball game. He bellows at current players with their “comfort breaks”—when he needed to urinate at a summer tournament in 1978 in Washington, D.C., he took a leak right on the court (no one noticed). And he hates their big serves. (Amazingly, in his five-set final against McEnroe at the 1982 Wimbledon, he didn’t record a single ace.)

Connors is almost proud of his years of poor sportsmanship: in the book he puts in a photo of him giving the middle figure with the caption, “That’s my body-double. I’d never do something so crude.” He recalls a match at the U.S. Pro Indoor in Philadelphia, where he got suspended for three weeks for an obscene gesture: “You can’t grab your nuts? I didn’t get that memo.” And on his website he has posted a number of archival videos of him engaging in egregious behavior.

His reasoning is simple: he was one of the first tennis pros (along with Nastase) to realize that in the open era, they had to be entertainers, not simply athletes on display. And for that, Jimmy Connors was the ultimate insider, playing the game of sports entertainment as well as anyone ever did.