Nobody can tell you with any certainty what makes a great song. Some have astonishing chord changes and insanely clever lyrics. Others are, um, well, think “Wooly Bully.” But trust a great musician to recognize a great song and, by extension, a great songwriter. So it should tell us something that the songs of J.J. Cale were covered by talents as disparate as Eric Clapton, Maria Muldaur, Jerry Garcia, Santana, Captain Beefheart, Waylon Jennings, Lynyrd Skynyrd, and Widespread Panic. Musicians couldn’t get enough of him. As for the listening public, they’re still catching up—but there’s lots of time for that: Cale’s songs were built to last.

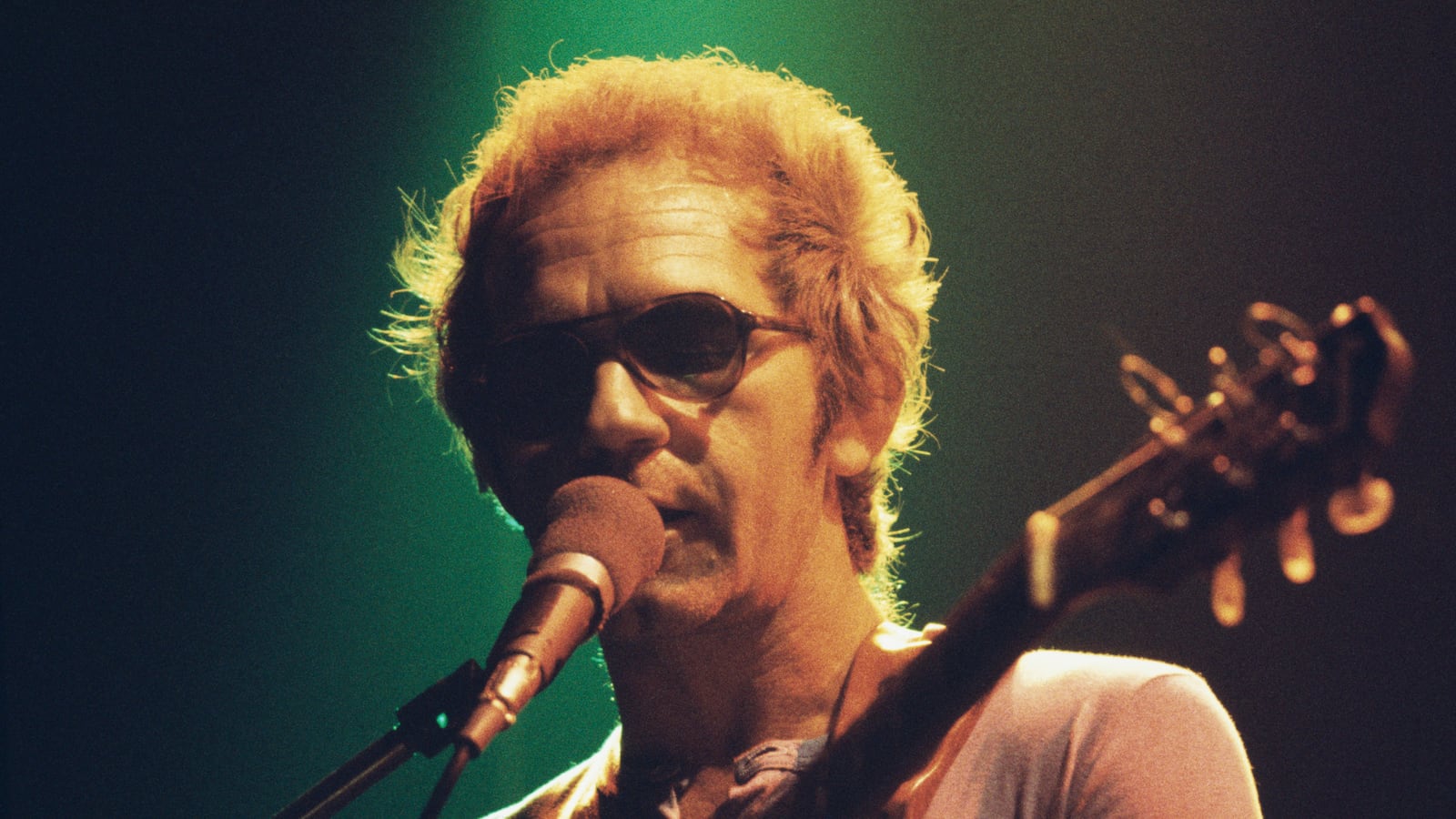

Cale, who died Friday of a heart attack at 74, never had a huge hit singing and playing his own material. “Crazy Mama” went to No. 22 on the charts in 1972, and that was as hot as he ever got, which by all accounts, including his own, was just fine with him.

“I stopped a lot of people who wanted to shove me into the real big time,” he told one interviewer. “Your ego wants to say, ‘Hey, I’m somebody, man,’ but I knew there were many days when I just wanted to be John Cale.” And if other people had great success with his songs, that was just fine, too. “What’s really nice is when you get a check in the mail,” he said.

Cale got a lot of those royalty checks after Clapton covered “After Midnight” and “Cocaine,” and Skynyrd covered “Call Me the Breeze.” If the world didn’t know his name, it sure recognized his music.

Born in Oklahoma City and raised in Tulsa, Cale grew up around other Oklahoma musicians such as David Gates (who would go on to front Bread), Leon Russell, and Carl Radle, Clapton’s bass player in Derek and the Dominoes. In the early ’60s, Cale joined the musical migration to Los Angeles, where he established himself as a producer, songwriter, multi-instrumentalist, and occasional performer.

As the years passed, he yo-yoed from California to Nashville and back, and by the time Clapton had a hit with “After Midnight” in 1970, Cale was once again living in Oklahoma. Someone told him Clapton had recorded the song, but he didn’t pay much attention until he heard it while driving one day in Tulsa. It was the first time he had ever heard one of his songs on the radio.

Success doesn’t seemed to have changed him much. He just kept on performing, doing studio work with musicians ranging from Neil Young to Art Garfunkel, and putting out the occasional album of his own stuff. In the meantime, he continued his itinerant existence, sometimes living for months in his Airstream trailer with no phone. When a reporter asked him in 1990 what he’d been up to, he said cycling, mowing the grass, and listening to Van Halen and rap.

On most of his records, he not only wrote and performed his own material, but he was his own band, overdubbing all the instruments. In interviews, he was likely to remain monosyllabic until the question of equipment arose. Then you couldn’t shut him up. He was a total gearhead. And an extraordinary guitar player: Neil Young once said that the two best electric guitarists he’d ever heard were Jimi Hendrix and Cale. In his autobiography, Waging Heavy Peace, Young writes: “‘Crazy Mama’ by J.J. Cale is a record I love. The song is true, simple, and direct, and the delivery is very natural. J.J.’s guitar playing is a huge influence on me. His touch is unspeakable. I am stunned by it.”

Cale’s musicianship and technical know-how, though, always served his songs. There’s no mistaking the skill behind his recordings, but it’s the songs you remember. Or more accurately, it’s the songs you can’t forget.

Without a trace of ostentation, Cale was able to blend a host of influences—country, folk, rock, boogie, jazz—into a seamless whole. His lyric patterns were mostly blues based, but you wouldn’t call him a blues singer. Instead, he was more of a magpie, listening to what came before and incorporating it into his own inimitable music.

Asked once if he resented Clapton’s success with his songs, Cale said no: “Clapton was just picking up ideas. He picked up some of mine like I picked up some from the people before me.” And all talk of royalties aside, there is no greater compliment for a singer-songwriter than to say that his songs live and thrive when played by others.

Still, if you want to hear Cale’s material at its best, seek out his versions. Elegantly simple and straightforward—and all the more mysterious for that—they get in your head and stay there, begging you to hit the repeat button.

With songs by, say, Stephen Sondheim or Brian Wilson, it’s almost too easy to say why they’re great. You can take their tunes apart like a Swiss watch, and the complexity of the constituent parts is what dazzles you. Cale’s songs, on the other hand, sometimes don’t even manage three chords, and the lyrics are just this side of prosaic. And yet, on the very first hearing, you feel like you’re meeting an old friend, and one with a lot of heart. His songs hardly seem written, much less slaved over. Instead, they seem like tunes and words that were always there, just out of reach, waiting for a receptive spirit to give them voice.

Rest in peace, J.J. Cale. And thanks for all the music that came with no expiration date.